Any time an organisation tells me with great confidence that they do Continuous Delivery, I am suspicious. When I probe for clarification and start asking specific questions, my suspicion typically gets confirmed. Tooling is in place, but the mindset and understanding of the principles, foundations, patterns or the central pattern behind Continuous Delivery are lacking.

Update Jan 10th, 2026: Clarify that the release cadence is defined by market demand.

Why still explain Continuous Delivery in 2026? Everybody does it, don’t they? But, do they really do? Is that really the case?

Over the years, I have interviewed a considerable number of technology organisations in the context of technology due diligence or observed technology organisations in the context of consulting. Many shared that they have Continuous Delivery in place. But, only a few really practised Continuous Delivery. There is a lot of misunderstanding about what Continuous Delivery actually is and what it entails.

As it often happens in our industry, people tend to redefine practices to ensure they fit their way of working, ignoring the basics and foundations. With this article, I revisit the basics of what Continuous Delivery genuinely is, with the goal of clarifying the principles behind Continuous Delivery.

Continuous Delivery is a holistic approach to IT delivery. It is a set of principles, foundations, and one pattern, backed by practices, that reduce the time between committing a change to a Version Control system - be it code for a feature, a bug fix, a configuration change, an infrastructure change or even just an experiment - and getting that change into the hands of the users in production safely, reliably, sustainably with confidence, and quickly. At the same time, all this, together with Lean Product Management and a Generative Organisational Culture (Westrum 2004), reduces stress, burnout and fatigue, and increases staff satisfaction and retention, and finally brings better organisational performance (Forsgren et al. 2016, Forsgren et al. 2018).

Nothing here is new. Details were already outlined in the 2006 paper The Deployment Production Line, the 2007 article The Deployment Pipeline, and later in the 2011 book Continuous Delivery: Reliable Software Releases Through Build, Test, and Deployment Automation. But, as it seems, many engineers do not read books (… and maybe many leaders do neither). Or they do read books, but have gone over the importance of the fundamentals, so they went looking for the cutting-edge. However, in all honesty, cutting-edge will not make it without mastering the boring basics that make the difference.

The basics, and the key to success, are about a mindset of excellence, both organisational and technological, of experimentation, of openness, and finally, that it will be alright, in the end, whatever we try.

It’s okay, it’s okay, it’s okay, it’s okay

If you’re lost, we’re all a little lost and it’s alright

It’s alright, it’s alright, it’s alright, it’s alright

– Nightbride, It’s OK

We have to understand that Continuous Delivery is not an endgame. It is not a project we implement once, and we are done. It is an exercise in continuous improvement that will never be over.

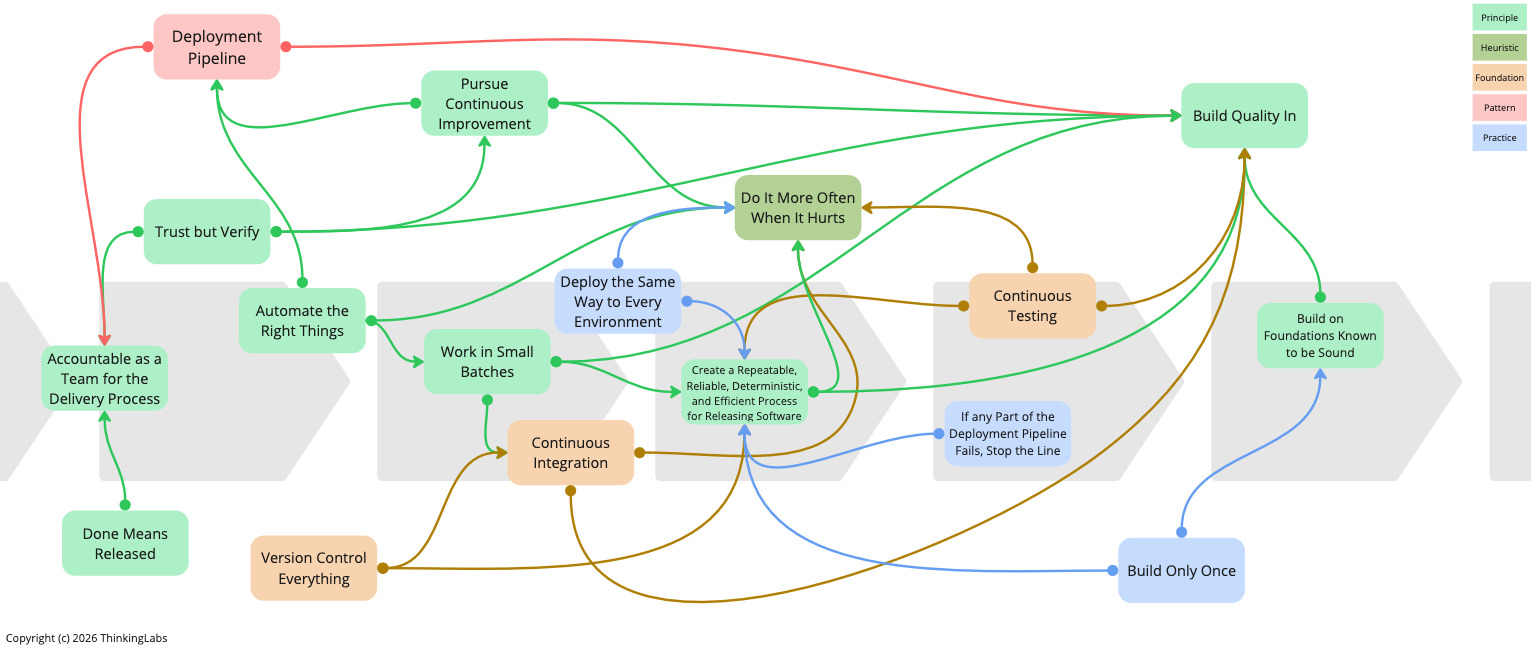

It takes nine principles, one heuristic, three foundations, one pattern and three practices to practice truly Continuous Delivery. Nevertheless, definitely worth the investment, as it increases staff engagement, delivers better products, and ultimately leads to higher organisational performance, such as more turnover, more market share (Forsgren et al. 2016, Forsgren et al. 2018).

- Nine Principles

- Accountable as a Team for the Delivery Process

- Done Means Released

- Create a Repeatable, Reliable, Deterministic, and Efficient Process for Releasing Software

- Build Quality In

- Build on Foundations Known to be Sound

- Work in Small Batches

- Automate the Right Things

- Pursue Continuous Improvement relentlessly

- Trust, but Verify

- One Heuristic

- Three Foundations

- One Pattern

- Three Practices

- Closing

Nine Principles

An effective IT delivery builds on nine principles. Not understanding these compromises the ability to obtain quality and efficient delivery.

Accountable as a Team for the Delivery Process

To achieve organisational goals - such as turnover, market share, productivity, quality of delivered goods, number of delivered goods, customer satisfaction - everyone in the organisation needs to be aligned with these goals.

All too often, development focuses on throughput, testing on quality and operations on stability. In reality, these are all system-level outcomes that help achieve organisational goals. They can only be achieved by close collaboration between everyone involved in the IT delivery process (Farley and Humble 2011). Ultimately, releasing IT systems is a team activity, not an individual activity. The whole team succeeds or fails as a team, together. Hence, the team is accountable for the delivery.

For this to work, it is crucial to implement the Deployment Pipeline pattern so that everyone in the team can see, at a glance, the status of the system, its health, the various builds, the results of the tests, and the state of the environments where the system can be deployed. This creates empowerment for the team (Farley and Humble 2011).

Done Means Released

A feature is only done when it delivers value to a user (Farley and Humble 2011). Inevitably, done means deployed into production and released to users.

There are cases where this is not particularly achievable. Think of mobile apps that need to go through a vetting process before landing in the app store. In this situation, we dial back to the next best option. Done means submitted to the store. At that moment, we have the actual binary release artefact, together with the release notes. If that is still a bridge too far, for valid reasons, we can dial one step back. It is done when it can be used and showcased in a production-like environment.

There is no such thing as 80% done. It is either done or not. It is very binary. There is no in-between.

This has an important corollary. One person from the team does not have the power to get something done. It is a team effort. It requires team members to collaborate to get it done (Farley and Humble 2011). Therefore, we have to be Accountable as a Team for the Delivery Process. It is the whole team’s responsibility.

Create a Repeatable, Reliable, Deterministic, and Efficient Process for Releasing Software

Releasing software should be easy and happen with confidence, without pain (Farley and Humble 2011). This reduces risks and, more importantly, stress for the team.

It is reliable, as with every run of the Deployment Pipeline, we test every single part of the release process, constantly (Farley and Humble 2011).

We demand efficiency to shorten the time to market and accelerate feedback to gain more information and run more experiments. Eventually, efficiency reduces the Cost of Delay. We want to know as quickly as possible if the thing we have just implemented, deployed into production and released to users is actually being used and how it is used. Based on this information, we can make new decisions and run new experiments to find new unmet needs of our users. As such, finding new ways to delight our users, which is a massive competitive advantage.

The repeatability, reliability and determinism derive from two foundations: Version Control Everything, and Continuous Testing; and two other principles: Do It More Often When It Hurts, and Automate the Right Things.

Interestingly, though repeatability, reliability and determinism derive from Do It More Often When It Hurts because if we want to do something more often, we need that repeatability, reliability and determinism. But, it is also a prerequisite to Do It More Often When It Hurts. There is that bidirectional influence, similar to quality and throughput, which amplifies each other.

Build Quality In

Cease dependence on mass inspection to achieve quality. Eliminate the need for inspection on a mass basis by building quality into the product in the first place.

– Edwards Deming, Out of the Crisis, point 3 from the 14 Points for Management

We cannot buy quality. We can also not test quality in later. Routine 100% inspection to “improve” quality is equivalent to planning for defects. We essentially acknowledge that the process lacks the capabilities to deliver quality (Deming, 1982).

Inspection to improve quality is too late. It does not improve quality, nor does it guarantee quality. The quality, good or bad, is already in the product. Mass inspection is unreliable, costly, and ineffective (Deming, 1982).

Split responsibility also means nobody is responsible (Deming, 1982). If the quality is the sole responsibility of the Quality Engineer, it tends to become a “throw it over the wall”. Quality Engineers are expected to catch the quality issues. Oftentimes, the opposite happens. Quality decreases. A similar behaviour occurs with blocking code reviews, security gating, or when the Ops team does the IT operations.

Quality comes from relentless continuous improvement of the delivery process (Deming, 1982).

With Continuous Delivery, we invest in a testing culture supported by people and tools where we detect any problems early and quickly, to fix them immediately when they are easy and cheap to find and resolve (Farley and Humble 2011). Quality is the entire team’s responsibility. Software Engineers implement automated tests with support and coaching from Quality Engineers. Quality Engineers coach the team into a quality mindset and use risks and heuristics to guide the testing.

Fiercely pursuing quality derives from one principle: Build on Foundations Known to be Sound; two foundations: Continuous Integration, and Continuous Testing; and one pattern: the Deployment Pipeline.

Build on Foundations Known to be Sound

Every stage of the delivery process builds on the previous stage (Farley and Humble 2011). Every stage adds more quality information to the Release Candidate. With each stage, the confidence in the Release Candidate is enhanced (Farley 2007). It passes the Unit Tests. It passes the Security Tests, the Acceptance Tests, and finally the Exploratory Tests. The objective is to develop a level of confidence in the Release Candidate to the point that it is proven ready for production deployment and release. We can now unequivocally choose whether to release the Release Candidate.

Building on foundations known to be sound, follows one practice: Build Only Once. The Release Candidate that gets deployed into production is the same one that went through all the previous testing stages.

Work in Small Batches

Reducing batch sizes represents a compelling opportunity. Following Little’s Law, it reduces lead time and thus time to market, and the Cost of Delay. Consequently, as lead time is shortened, feedback is accelerated. Because we now have smaller batch sizes, we are less exposed to changes, and as such, we reduce risks because the consequences of an error are much smaller. Smaller batch sizes reduce overhead. With Continuous Delivery, we can reduce the cost of repetitive transactions caused by many small batches. Finally, because feedback is accelerated, we improve efficiencies (Reinertsen 2009).

Large batches inherently lower motivation and urgency. It demotivates people by delaying feedback. Large batches dilute responsibility. Ultimately, it leads to risk avoidance and accordingly disables innovation. Finally, large batches attract even larger batches (Reinertsen 2009).

By splitting work into much smaller chunks that deliver measurable value quickly, we receive essential feedback on the work we are doing so that we can course-correct. Continuous Delivery changes the economics of the IT delivery process, making the cost of pushing out small individual changes very low (Farley and Humble 2011), by reducing the transaction cost, allowing to make many smaller, more frequent changes. Obviously, this demands to Make All Changes In Small Increments.

Working in small batches derives from two other principles: Create a Repeatable, Reliable, Deterministic, and Efficient Process for Releasing Software, and Automate the Right Things.

Automate the Right Things

Computers perform repetitive tasks; people solve problems. To reduce the transaction cost of pushing out many more, smaller changes, we should invest in simplifying and automating repetitive work that takes time, such as manual regression testing and manual release processes. This frees up teams for higher-value problem-solving activities, innovation and value creation (Farley and Humble 2011). Automation accelerates feedback, therefore multiplying learning and discovery. It supports faster, more reliable releases. Most importantly, it vastly reduces risks and enables to Work in Small Batches.

Note that this principle is nuanced. It does not say “Automate all the things”. In that case, there is a risk of overinvesting. In consequence, we only automate bottlenecks, repetitive tasks, or tasks that involve high risks. For that, we ought to map the technology value stream from Version Control to the user, and identify bottlenecks, risks and repetition. This technology value stream map is now the starting point to implement the Deployment Pipeline. By automating the identified steps, we start building the Deployment Pipeline iteratively.

Spending time optimising anything other than the bottleneck is an illusion.

Eliyahu Goldratt, The Goal

Pursue Continuous Improvement relentlessly

Improve constantly and forever the system of production and service.

There must be continual improvement in test methods, and even better understanding of customers’ needs and of the way [they] use and misuse a product.

– Edwards Deming, Out of the Crisis, point 5 from the 14 Points for Management

Continuous Delivery requires the adoption of a set of technological changes - Version Control, trunk-based development, Continuous Integration, Continuous Testing, Deployment Pipeline, automated configuration, Infrastructure as Code, evolutionary architecture, database migrations, monitoring and alerting, incremental releases (Smith 2020) - as well as organisational changes - Small Batch Sizes, empowered product teams, cross-functional teams, shared incentives, blameless post-mortems, you build it, you run it, everyone does on-call, continuous change review, traceability of changes, upskilling and empowering staff, Conway’s Law alignment, Continuous Improvement (Smith 2020).

Adopting Continuous Delivery is hard work. It requires applying all of these changes to the unique circumstances and constraints of the organisation. Implementing Continuous Delivery will, henceforth, not happen overnight, as already mentioned in Automate the Right Things. It will be the result of continuously improving the IT delivery process.

In the end, an organisation is a complex adaptive system in which behaviours emerge from unpredictable interactions. The cause and effect of an event can only be understood in retrospect. Every individual has only a limited amount of information. No one has a complete overview of the whole delivery process. Consequently, adopting Continuous Delivery means implementing changes in highly uncertain conditions.

To move forward, we need something to guide us. We need a continuous improvement framework such as the Improvement Kata, that helps us to execute and measure organisational change to reach goals in uncertain conditions. Due to the uncertainty, we do not know how the results will be achieved. Progress is non-linear. Accordingly, the framework guides experimentation and problem-solving.

As already mentioned in the introduction, adopting Continuous Delivery is not a project with an end date. It is the result of this continuous improvement. As such, the Deployment Pipeline will be built incrementally, as already outlined in Automate the Right Things.

Again, to succeed, it is invaluable that everyone from the team is involved (Farley and Humble 2011) and as such Accountable as a Team for the Delivery Process.

Trust, but Verify

This principle is not mentioned in the Continuous Delivery book. However, I find it particularly imperative as it constitutes the essence for enabling safety, courage, and Accountability as a Team, which are all required to Build Quality In and Pursue Continuous Improvement relentlessly.

It is the lack of trust that has initiated all sorts of unnecessary, wasteful activities (such as blocking code reviews, quality gates, security reviews, change approval boards, biannual releases, etc.) to the process of getting code from Version Control into the hands of the users, which reduce feedback, impact quality, create fatigue, burnout and disengagement, slow down delivery, and finally bring organisations to a halt without them noticing it. Only to create some sort of sense of control. Not true control, just a sense.

This lack of trust creates information silos, fosters hidden communication channels, gradually ceases innovation, and values the illusion of work over quality of effort (Wieczoreck 2025).

But, but … people will dump rubbish.

If that were the case, it would be a system problem. According to Deming, system problems are created by management. This conveys that it is management’s responsibility to remove barriers and constantly improve the system.

So the natural thought is just clogged up, totally clogged up.

So we need to unplug these dams and make the natural flow

– Gorillaz, Stop the Dams

Instead of thinking people are stupid and so we need a process to fix for that, leadership should enable people to do the right thing and then trust they will do the right thing. This is about applying Management Theory Y over X. Then, to verify that the trust is not abused, to ensure accountability, and to balance belief with due diligence to prevent errors or deceptions through monitoring, regular reviews, and audits. But! This verify can also easily be misused to destroy the trust, especially if it comes from outside. Some teams might indeed abuse the autonomy and trust, not necessarily intentionally. Paved roads and guardrails introduced by platforms will help teams to do the right thing. In essence, it is more about following up, guiding teams, and giving them the benefit of the doubt. Remember, a mindset of everything will be alright, whatever happens.

Adopt and institute leadership.

The job of management is not supervision, but leadership. Management must work on sources of improvement.

– Edwards Deming, Out of the Crisis, point 7 from the 14 Points for Management

Trust is a business’s primary currency. Investors need it to ensure they are spending their money on the right companies. Clients need to know they are in safe hands to spend their budget. Staff need to hear their leadership has their backs if they are to execute on their company’s vision (Joshi 2023).

Together with accountability, it fosters a culture of openness, experimentation, learning, and, in consequence, brings increased innovation and Building Quality In. In conclusion, staff who feel trusted perform better, and as a result, lead to higher organisational performance (Joshi 2023).

… [publicly traded] stocks of companies with a high trust work environment outperformed market indexes by a factor of three from 1997 through 2011 (Azzarello et al. 2012).

Employee engagement is not just a feel-good metric - it drives business outcomes.

– Accelerate

One Heuristic

Do It More Often When It Hurts

Bring the pain forward (Farley and Humble 2011).

When integrating software is hard, do it on every commit, with the Continuous Integration foundation.

When testing is painful, that only occurs before a release, do not leave testing to the end. Testing is not a phase! But Build Quality In by adopting the Continuous Testing foundation, from the start. Having said that, even with Continuous Testing, testing can still be painful due to arduous setups to reach a state where testing can start, or a lack of observability to see what is happening inside the system, or bumping into permission issues. This requires Continuous Improvement to remove all of these blockers.

When releasing is laborious and distressing, shift from releasing once a year to biannually, to quarterly, to monthly, weekly, and eventually daily or even multiple times per day. This builds on the principle to Automate the Right Things, and the practice of Deploying the Same Way to Every Environment.

At the same time, the chosen release cadence must be a business decision. Continuous Delivery has a dynamic success threshold. An organisation is said to be in a state of Continuous Delivery when its IT services have the required stability and throughput to satisfy market demand. If releasing monthly satisfies demand, we are in a state of Continuous Delivery. That does not mean that, internally, we should not produce Release Candidates daily. We definitely should, for every commit!

When writing documentation is tedious, do it immediately when implementing the feature or the architectural change. Make the documentation, release notes, runbooks, and decision records part of the Definition of Done.

Admittedly, depending on our situation, this may require considerable effort and investment. But it is certainly an investment. It is not a cost. It has a return. In the long run, it induces a more reliable, consistent, and efficient delivery process, reducing stress and burnout. It provides better business outcomes, allows for new opportunities, stabilises current customers, increases reputation, creates more turnover, and gains more market share. It is a synergy effect that is often forgotten. Hence, we have to Pursue Continuous Improvement relentlessly.

Three Foundations

Implementing Continuous Delivery calls for indispensable foundations.

Version Control Everything

Without version control, we miss a single source of truth. Releasing a piece of software becomes a marathon of chasing bits and pieces of code on engineers’ machines or shared network drives. It also becomes quite challenging to roll back to a previous version known to be good, due to a lack of a single source of truth.

Consequently, it is a foundational practice to succeed with Continuous Integration and by extension with Continuous Delivery.

Continuous Integration is a state we accomplish as a team, not as an individual. Subsequently, to work as a team, we need a way to coordinate code.

Therefore, everything we need to build, test, deploy, release, run and operate our application must be kept under Version Control (Farley and Humble 2011) in one single repository. This means we version production code, obviously, but also all of our tests, build and deploy scripts, deployment pipeline code, application and system configurations, database schema migrations, all the infrastructure required to run the system, but also documentation, decision records and runbooks to maintain and keep the application available.

Keeping production code, test code, infrastructure code, and configurations in different version control repositories is an antipattern. It complexifies the implementation of the Deployment Pipeline and creates cognitive load. Anyone on the team should be able to clone an application’s repository and discover, at once, everything needed to build, test, release, run, and operate the application, without having to clone any more repositories.

Know that the Version Control System is more than just versioning. It is a communication tool to share changes with team members. It supports gaining a Shared Understanding of the system and building a Collective Ownership over the codebase. In turn, it allows for increased integration frequency. As a consequence, it enables communication and collaboration within the team. All the good ingredients for Building Quality In and higher delivery throughput.

Continuous Integration

Continuous Integration is a Team Practice. We realise it as a team, not as individuals. Most of the time, practices are defined for individuals. When most team members apply them, the team does well. However, with Continuous Integration, most team members must implement other practices before the team can declare they practice Continuous Integration.

Without Continuous Integration, our software is broken until somebody proves it works. With Continuous Integration, our software is proven to work with every new change - assuming we have a decent set of comprehensive automated tests -, and thus, we know the moment the software is broken.

Following the principles of Work in Small Batches and Building Quality In, we push at least once a day into Mainline (more is better). Every commit triggers an automated build and execution of the automated tests. When the build fails, it gets fixed within ten minutes.

If we fail to implement any of these three criteria (push once a day, triggers a build, and fixed within ten minutes), we clearly do not practice Continuous Integration. Achieving Continuous Integration entails adopting 20 practices. As with accelerating releases, this is a journey. So, where do we start?

Continuous Integration is a prerequisite to Continuous Delivery. Although we have seen organisations reach Continuous Delivery without Continuous Integration. But that is not sustainable in the long term. Teams will be operating at higher levels of risk for delayed delivery or production failures than people can actually tolerate. This will create a higher risk for stress, fatigue and burnout. Which inevitably impacts organisational performance.

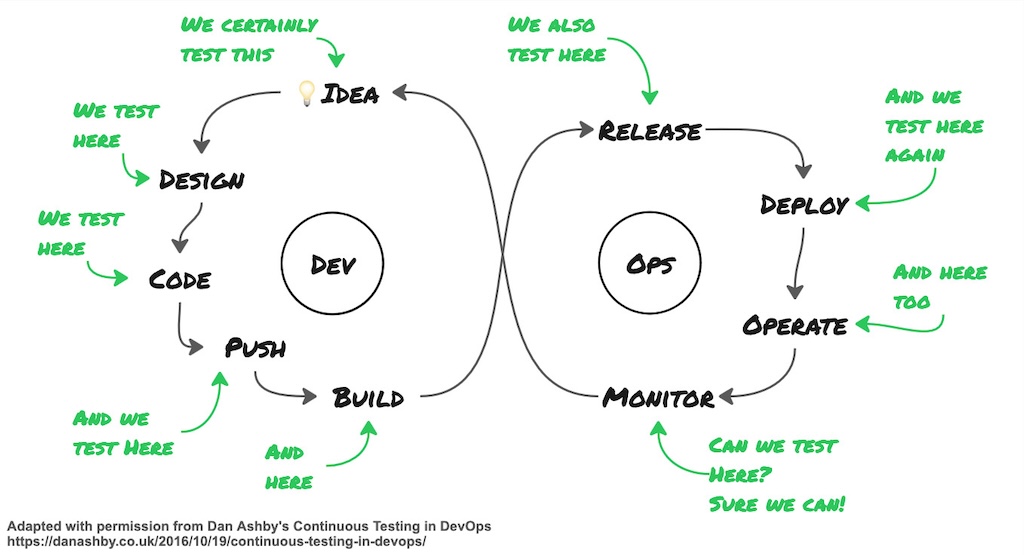

Continuous Testing

Following the principle of Building Quality In, testing has to be an integral part of the delivery process. We test at all stages of the value stream. This requires a multifaceted testing strategy that should be both automated and manual.

All features or improvements start from an idea. Testing the idea is critical. Does the idea make sense? Are users waiting for it? Does it solve a problem? We investigate the idea to uncover more information, enhance and crystallise it. User research and user interviews are an elementary part of testing the idea.

We test the design. It is exploratory in nature and risk-based. We use risks and heuristics to focus our investigation. While asking questions, we uncover more information that helps to refactor the design, to make it better (Ashby 2016).

We can investigate the code. Check it against expectations discussed during planning. Code reviews are exploratory testing to scrutinise wrong assumptions. When writing Unit Tests, we can pair with a Quality Engineer who can share test ideas about different risks, interactions, and perspectives (Ashby 2016).

We test the push, i.e. the merge of the local Mainline with the remote Mainline, using Continuous Integration.

We can certainly test the build (Ashby 2016).

We conduct Exploratory Testing of the product, on a local workstation, or in a test environment.

When releasing, we can test the release and the deployment with Smoke Tests (Ashby 2016), and, eventually, with more Exploratory Testing in production.

Finally, there is monitoring. Monitoring is about the known knowns. The things we can alert upon. As such, monitoring also requires testing. Does it provide the expected information? Does it alert?

On the other hand, observability is testing too, and also exploratory in nature. We explore usage patterns. It tells us how the system is being used by users, which feeds into new ideas.

Continuous Testing is evidently more than only automated tests. We cannot rely solely on automated tests. Teams attempted that in the 2000s, with the rise of automated testing frameworks such as xUnit, among others. It did not work out well. Quality problems still arose. Some issues can simply not be detected with 100% coverage. Automated testing is excellent for guiding design, revealing when a feature is complete, and a substitute for manual regression testing, i.e. the known knowns. It will not uncover faults of omission or unexpected user behaviour, to name a few, the unknowns. As expressed earlier, it calls for a multifaceted testing strategy that encompasses both manual and automated testing. Accordingly, manual testing is an invaluable factor. But it should never be a gate.

Though when implementing Continuous Delivery, we have to Have A Vast Amount of High-Quality Automated Tests on top of the manual testing. It ensures we create multiple feedback loops to deliver high-quality software to users more frequently, reliably and sustainably (Farley and Humble 2011). The key pattern which connects these feedback loops is the Deployment Pipeline.

One Pattern

Deployment Pipeline

Some call it CICD-pipeline, some DevOps pipeline, but the true name of the pattern is manifestly the Deployment Pipeline (Farley 2007, Farley and Humble 2011).

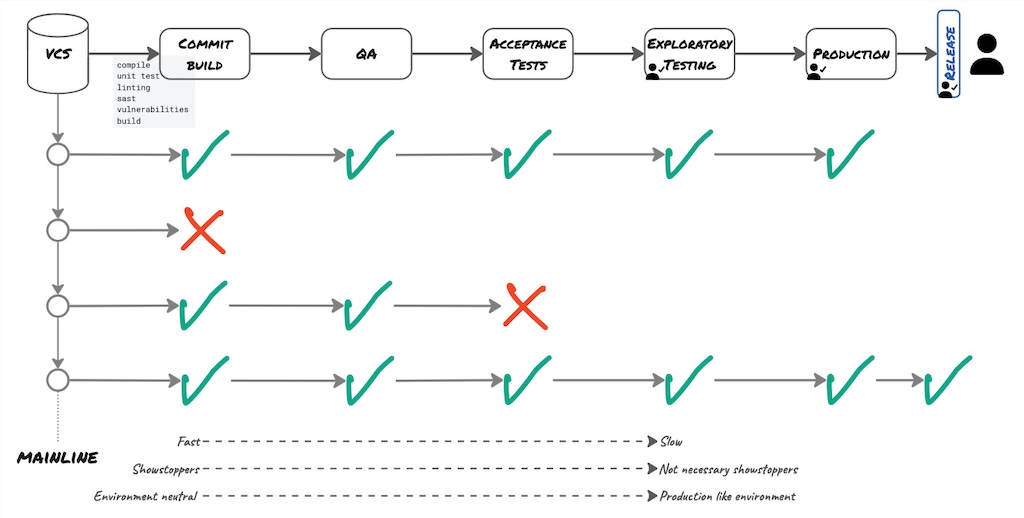

One of the rare occasions in IT where the factory metaphor applies is the technology value stream, because it is a homogenous process where every step is deterministic, much like an assembly line. The Deployment Pipeline is some sort of an assembly line, a conveyor belt. It is the automated manifestation, consisting of several stages, to get software out of Version Control, test the software, package the software, run additional tests and ultimately bring it into the hands of the users in production.

The Deployment Pipeline is the implementation of the technology value stream that is part of the overall value stream to take an idea about a feature out of the mind of users, Product Manager or team, into the hands of the users. Hence, it only covers the downstream part of the value stream from Version Control until production and releasing.

The objective of the Deployment Pipeline is to eliminate bad quality Release Candidates as early as possible. It acts as a sequence of gates (Farley 2007). Whenever a stage is red, it discards the Release Candidate. As such, only changes that successfully went across all stages of the deployment pipeline and have been thoroughly tested, get into production.

The Deployment Pipeline comprises several stages. Some are automated, others are manual. It is perfectly okay to have manual steps in the Deployment Pipeline. Often, the implementation of a Deployment Pipeline starts from the technology value stream map from Version Control to production. It might be that at the start, all those steps are still manual. Then, following the Pursue Continuous Improvement relentlessly and Automate the Right Things principles, we automate the steps that form a bottleneck or are risky or repetitive.

Some stages will have automatic thresholds. For instance, when an automated test fails or a vulnerability is found, the stage will turn red and reject the Release Candidate. Other stages require human intervention to evaluate the results, such as for load or performance testing, where it is difficult to define a distinct baseline.

The stages at the start of the Deployment Pipeline are fast. As we progress in the Deployment Pipeline, the stages become slower. We prioritise the fast stages first to accelerate feedback. That is the reason we execute the fast Unit Tests in the first Commit Build stage and only execute the slower Acceptance Tests in a later stage.

Note that the Commit Build serves as a Commit Gate. Once it passes, it frees engineers to move on with new tasks (Farley 2007).

Because the first stages are fast, they are also environment-neutral. Where Automated Acceptance Tests and Load Testing need to happen in a production-like environment. By contrast, Exploratory Testing can, as part of a Continuous Testing mindset, already occur in an early stage in an environment-neutral setting and can also happen again in a production-like environment or even production using different test charters.

Stages at the start are also showstoppers. Meaning, if these fail, they discard the Release Candidate. Further down the Deployment Pipeline, they are not necessarily showstoppers. Some, like the Automated Acceptance Tests, must be; others not. As Exploratory Testing is not regression testing, it does not necessarily eliminate the Release Candidate. That is a reason for the Exploratory Testing not to be on the path to production. It could be limited to production.

The Deployment Pipeline has three purposes:

- Make every part of the process of releasing software visible to everyone.

- Improve feedback to identify problems early when they are still small and easy to fix, and therefore to resolve them quickly.

- Empower teams to deploy any version of the system to any environment as they please, limiting the wait time and improving lead times.

All three purposes are important, though point one - make every part of the process visible - is especially paramount. It calls to maintain only one, single Deployment Pipeline per binary artefact.

With the rise of GitOps, we now see implementations consisting of two pipelines. The so-called “CI-pipeline”, usually including only one single stage, the Commit Build, which produces the binary artefact. The “deploy pipeline” implemented using a different tool that promotes and deploys the binary artefact in the subsequent environments. This antipattern infringes on the visibility purpose. Identifying which commit landed in which environment takes effort. Measuring Continuous Delivery becomes difficult. Automating the execution of the Automated Acceptance Tests might be tricky and certainly not straightforward, which generates complexity. Lastly, it enlarges the technology landscape and thus the cognitive load for the team. To summarise, with GitOps, it is decidedly challenging to attain Continuous Delivery.

The Deployment Pipeline is the logical extension of Continuous Integration, where every commit creates a potential Release Candidate, following the Build Only Once practice, after which the Release Candidate is promoted from stage to stage to, at last, arrive in production.

Lastly, the deployment pipeline code is handled in a similar way to production code. It is versioned, evolves with refactoring, and abstraction and Single Responsibility design principles apply.

Three Practices

Build Only Once

Delivery systems based on recompiling code and rebuilding binary artefacts for each environment are flawed. Every time we rebuild, we run the risk of introducing some differences (Farley and Humble 2011). The compiler version could be inconsistent, or its configuration. We could pick up different versions of third-party libraries. In essence, we wish to minimise the opportunities for errors to creep into the process (Farley 2007).

This rebuilding antipattern violates two principles: Create a Repeatable, Reliable, Deterministic, and Efficient Process for Releasing Software and Build on Foundations Known to be Sound.

Rebuilding violates Create a Repeatable, Reliable, Deterministic, and Efficient Process for Releasing Software, as rebuilding takes time. Also, every rebuild requires retesting. This quickly becomes a lengthy process, with long lead times that come along with a Cost of Delay. Not retesting defies determinism and reliability.

It disregards the Build on Foundations Known to be Sound, as it enables the risk that some changes have been introduced between the creation and subsequent testing and the release of the binary artefact.

Therefore, binary artefacts should be built only once, by the Commit Build stage, to ensure that the binary which gets deployed into production is exactly the same as the one that went through the Automated Acceptance Testing stage, and any other testing stage that may well be present. Each binary artefact is tagged with the version information of the source code they were built from. The tag is a Release Candidate identifier, also commonly known as a version number (Farley 2007). Today, this could be a combination of commit-SHA and built timestamp (or commit timestamp). This ensures traceability between the binary and the source code version that triggered the build.

This is the precise motive for GitFlow to be incompatible with Continuous Delivery. It forces a rebuild to deploy in production and release. With GitFlow, it is decisively impossible to reach Continuous Delivery.

Deploy the Same Way to Every Environment

It is key to use the same process to deploy to every environment, whether into testing environments or production, to ensure the build and deployment process has been tested effectively (Farley and Humble 2011).

The frequency of deployment is inversely related to the risk associated with each environment. We will deploy frequently to the test environment, but less to production. Before deploying to production, we will have tested the deployment many times in the upstream environments to discard any possible errors.

This implies we must use the same script and the same binary artefact to deploy to each environment. Of course, environments differ from each other. Surely, they will have different IP addresses, different database connections and other external services. Therefore, we separate binary artefacts and deploy scripts from configuration and keep the configuration outside (Humble et al. 2006) of the deploy script in configuration files under Version Control, and secrets in vaults, also under Version Control.

As for build scripts to Automate the Build, and the deployment pipeline code, the deploy script is treated the same way as production code. It is versioned, tested, and evolves continuously through refactoring. We apply similar design principles as for production code, such as abstractions, small files, Cohesion and Coupling, Simple Design, and Single Responsibility Principle.

Deploying the same way to each environment guarantees repeatability, consistency and determinism. The deploy script has to be idempotent. Deploying the same version of the system over and over again in an environment results in the same outcomes without any side effects.

If any Part of the Deployment Pipeline Fails, Stop the Line

To establish rapid, repeatable, reliable releases, we have to accept as a team that every change, every commit into Version Control, will successfully build, pass every test and deploy (Farley and Humble 2011). In that case, Agree as a Team to Never Break the Build extends to the whole Deployment Pipeline. This implies that if any part of the delivery process fails, the team owns the failure, Stops The Line, and fixes it immediately before moving on with any ongoing work. This is vital to Build Quality In.

Closing

As demonstrated, Continuous Delivery is another discipline where the lack of tooling is not the problem, as is the case for Continuous Integration. To be successful with Continuous Delivery, and henceforth have a performant, reliable, deterministic IT release process, calls for an understanding of the principles, the foundations, the one pattern and the practices.

Continuous Delivery is essentially about applying the ideas from Continuous Integration to the entire IT delivery and release process.

Despite everything that has been said, where do we start? Again, context matters. The journey that worked for one organisation will not necessarily work for another organisation. With the Improvement Kata we consider the organisation’s context. We start by defining a vision. Then we iterate towards the vision using the PDCA-cycle together with Theory of Constraints to find the bottleneck, and thus identify the experiments most likely to succeed. This has been outlined in the case study From bi-annual to fortnightly releases in 4 months for 15 teams and a single monolith.

Once we fathom all of that, the rest will follow, naturally. It becomes a virtuous cycle where quality leads to higher throughput, and throughput leads to even better quality.

Je n’ai fait cette lettre-ci plus longue que parce que je n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte.

– Blaise Pascal, Les Provinciales, Seizième lettre (1656)

Acknowledgement

Lisi Hocke, Gitte Klitgaard, my colleagues Eduardo da Silva and João Rosa, and my best friend Martin Van Aken for their precious feedback that helped in creating a well-rounded, balanced article. Thank you, my friends!

Related Articles

References

- Out of the Crisis, Edwards Deming, 1982

- A typology of organisational cultures, Westrum, 2004

- The Deployment Production Line, Jez Humble, Daniel North, Chris Read, 2006

- The Deployment Pipeline

- The Principles of Product Development Flow, Donald Reinertsen, 2009

- Improvement Kata, Mike Rother, 2009

- Continuous Delivery: Reliable Software Releases Through Build, Test, and Deployment Automation, Dave Farley, Jez Humble, 2011

- The chemistry of enthousiasm, Dominico Azzarello, Frédéric Debruyne, Ludovica Mottura, 2012

- The Role of Continuous Delivery in IT and Organizational Performance, Nicole Forsgren, PhD, Jez Humble, 2016

- Continuous Testing in DevOps, Dan Ashby, 2016

- Accelerate: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations, Nicole Forsgren, PhD, Jez Humble, Gene Kim, 2018

- Measuring Continuous Delivery, Steve Smith, 2020

- The effects of low trust in organisations, Rahat Joshi, 2023

- 5 Hidden Consequences Of Leaders Not Trusting Employees, Kate Wieczorek, 2025

- From bi-annual to fortnightly releases in 4 months for 15 teams and a single monolith, Thierry de Pauw

Definitions

Mainline

The Mainline is the line of development in Version Control, which is the reference from which system builds are created that feed into a Deployment Pipeline.

For CVS and SubVersion, this is trunk. For Git, this is the remote main branch. For Mercurial, this is the remote default branch.

Commit Build

The Commit Build is a build performed during the first stage of the Deployment Pipeline or the central build server, triggered by a commit in the Version Control System. It involves checking out the latest sources from Mainline and, at a minimum, compiling the sources, running a set of Commit Tests, and building a binary artefact for deployment.

Commit Tests

The Commit Tests comprise all of the Unit Tests along with a small, simple smoke test suite executed during the Commit Build. This smoke test suite includes a few simple Integration and Acceptance Tests deemed important enough to get early feedback.