This first part of this series investigates the practices that enable teamwork that in turn enable Continuous Integration. Continuous Integration is a Team Practice. We achieve it as a team and not as a set of individuals. Most of the time, practices are defined for individuals. When most team members apply them, the team does well. However, with Continuous Integration, most team members have to implement other practices before the team can say they practice Continuous Integration.

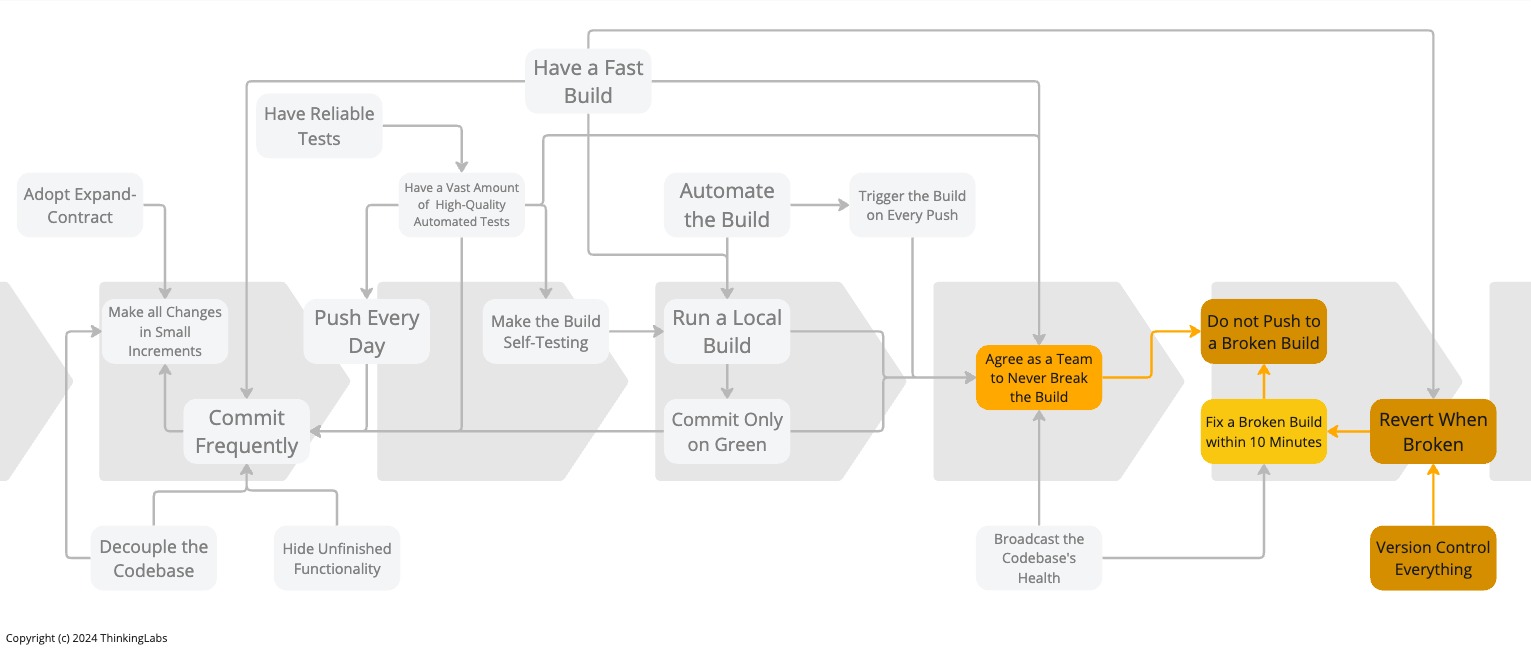

Update Sept 12, 2024: Add the infographic.

The difference between a tool and a practice is that a practice only exists when you are doing it.

– Steve Chapman, Tools versus Practices - Lessons learned from DIY

Tools are very appealing to many engineers because, often, engineers hope by adopting a tool, they get the practice for free. Though, again and again, that is not true.

On the other hand, a practice is the actual application or use of an idea, belief, or method. It is a codified way of working that might involve some tooling to achieve the practice, but generally, no tooling is required.

Practice 1: Version Control Everything

We would think, by 2022, this would be obvious. It seems the inverse is still true (rolling eyes).

Historically I meet 1 team a year on average who aren’t using version/source code control. Common reasons:

- very immature team

- SQL

- PickOS derivative or ERM/CRM system

Last category may even lack tooling

– Allan Kelly (@allankellynet), Nov 8, 2020

Continuous Integration is a state we accomplish as a team, not as an individual. Therefore, to work as a team, we need something to coordinate production code, test code, application and system configurations, database schema evolutions, infrastructure code and many other things.

Without version control, we do not have a single source of truth. Releasing a piece of software becomes a marathon of chasing bits and pieces of code on engineers’ machines or shared network drives.

Without version control, we may need a team of integrators to integrate the code before releasing it. It will lead to far fewer integrations per day, in turn impacting the quality and throughput of the IT delivery process together with the lead time for delivery and time to market.

Without version control, it becomes damned hard to roll back a deployment that went awry because we do not have that single source of truth allowing us to go back to the last known good state.

If we do not version every single artefact required to create the software application we will not enjoy any of the benefits of Continuous Integration. All of the practices that make Continuous Integration and that are pre-requisite to Continuous Delivery rely on having everything under Version Control. All of these practices help to reduce the IT delivery lead time and increase quality.

Be aware that a Version Control System is not only about versioning source code. It is first and foremost, a communication tool to communicate changes amongst all team members. Together with Continuous Integration, it reveals the impact on others within minutes. It helps in gaining a Shared Understanding of the system and building a Collective Ownership over the codebase. In turn, this will allow for increased integration frequency. Consequently, this enables communication and collaboration inside the team. As a result, it enables the fast flow of work through the value stream. Inevitably, this results in better quality and higher throughput for the IT delivery process and thus for a shorter time to market.

In the past I have gone to extraordinary lengths to version intractable software, I recall our team reverse-engineering the RDBMS storage that backed an ESB system, and inventing a DSL that we could script the ESB config with so that we could store it in VCS 🙄

– Dave Farley (@davefarley77), Nov 8, 2020

This is the first of two practices that effectively need a tool to implement the practice, i.e. we need a Version Control System. The other practice is Automate the Build. To be clear, Automate the Build is not about having a “CI-tool”. It is about having a build script. We will get to that in more detail in part 3 - Building for Continuous Integration. All other 12 practices do not need any tooling at all. In the end, to carry off Continuous Integration, we only need two tools. But we will need to implement 14 practices.

Practice 2: Agree As a Team To Never Break The Build

Get every one of the team to agree to the following:

From now on, our code in revision control will always build successfully and pass its tests.

– James Shore, Continuous Integration on a Dollar a Day

I am putting this in bold because, without any doubt, this is unquestionably key to the success of achieving Continuous Integration as a team. It ensures we have always working software. It guarantees the code we get out of version control simply works at any given moment in time assuming we have a sufficiently comprehensive set of automated tests.

But, to be honest, it only reveals the known knowns. At this point, we do not know if the system is valuable for users. We do not understand how it behaves in front of the users. That is where manual exploratory testing will add more information. However, not breaking the build ensures manual exploratory testing can actually happen and that we can deliver a working system to users so we can, in effect, learn how it behaves in front of the user.

That said, this practice is non-negotiable. There is no single acceptable reason that would allow breaking this agreement. Even if production is burning. Nevertheless, it requires to Run a Local Build, Commit Only on Green, Have a Vast Amount of High-Quality Automated Tests and Have a Fast Build. But how many tests is vast? If we have a considerable amount of tests, does that automatically mean we have the right tests? And when is a build fast? That too will be discussed in more detail in part 3 - Building for Continuous Integration.

If we do not get everyone in the team to agree to this, Continuous Integration will clearly not work for our team. That is a fact! When the build is broken we do not have Continuous Integration. Without Continuous Integration, our software is broken until someone else proves it works.

After all, the reason for integrating code is to gain confidence about the quality of the code in the version control system. When the build breaks, the scope of possible root causes is broad. We are not so sure where to look. Therefore, reducing the range of potential root causes is essential to developing quickly and, as such, increasing IT delivery throughput. If we know our code worked five minutes ago, we only need to consider our actions from the past five minutes when investigating a broken build. That considerably reduces the scope for finding the root causes. Usually, we only need to look at the error message to understand what is wrong. No debugging is required.

Therefore, agree as a team to never break the build.

To attain this, it requires everyone in the team to fetch the latest changes first from the remote Mainline and Run a Local Build before committing into Mainline. When the Local Build was successful, push to the remote Mainline and wait till the Commit Build passes to green before starting new work. In all honesty, that is not yet a guarantee for the Commit Build not to break. As Seb Rose rightfully observed, it is still possible to have a broken Commit Build when two engineers Run a Local Build simultaneously. That is why waiting until the Commit Build passes is so essential.

Practice 3: Do not Push to a Broken Build

If the build happens to break, we Stop The Line and fix the build immediately.

During the time the build is broken, no new code is added. Adding new code only aggravates the situation by adding more problems and triggering new broken builds. In the end, it makes the failure even worse. Fixing the broken build becomes harder and harder. At a certain point, people get used to seeing a broken build. Quickly this results in a situation where the build stays broken all the time. From this moment on, we have lost the health monitoring for our application. Inevitably this impacts the quality of the software. Accordingly, we also lost the ability to perform on-demand production releases at any time. Naturally, this reduces IT delivery throughput and increases our time to market.

The most crucial step in reaching Continuous Integration as a team is to accept as a team that each time code is committed, it builds successfully and passes every test without exception. If the build fails, the whole team owns the failure. Hence, Agree As a Team To Never Break The Build. Therefore, when the build fails, the whole team stops and fixes the build before moving on with anything else. To realise Continuous Integration it is imperative to adhere to the rule of not adding new code while the build is broken. Again, when the build is broken we do not have Continuous Integration. Adding new code on top of a broken build will keep the build broken for a more prolonged time, keeping the team farther away from Continuous Integration.

Practice 4: Revert When Broken

One of the preconditions of being in a state of Continuous Integration is to fix a broken build within ten minutes. The longer it takes to fix the build, the longer we block a whole team. Given the salaries for IT engineers, that is quite a lot of money held in standstill. What is more, it disables on-demand production releases. Consequently, it reduces IT delivery throughput and increases time to market.

But why within ten minutes? Why not within five or 15 minutes? Because this is related to Have a Fast Build. If the build is under ten minutes, quickly fixing the problem and re-running the build will work if the fix is easy.

However, if we cannot fix the problem right away, then the easiest and fastest way to fix a broken build within ten minutes, and ensuring not to impact the time-to-market, is to revert the commit that caused the broken build. It allows us to go back to the last known good state of our application codebase. Obviously, this requires Version Control Everything, otherwise reverting will become a battlefield.

If you do revert a broken deployment, why would you not revert a broken build?

– Steve Smith during a phone call

Conclusion

Investing in these practices is very valuable. Each on their own enables the fast flow of work for the team. Each on their own enables more integrations. The more integrations happen, the closer the team gets to a state of Continuous Integration. However, these are demanding practices to adopt as it involves people. But implementing these practices is a good investment, not a bad cost, as it unlocks faster IT delivery throughput and higher quality.

Acknowledgments

Lisi Hocke for reviewing, genuinely questioning what I wrote from a tester’s perspective and all the cheering.

Seb Rose for his extreme kindness to offer at SoCraTes his precious time to review this article and for finding the bugs in my reasoning.

As always, my dear friend Steve Smith for his discerning and to-the-point feedback.

Bibliography

- Tools versus Practices – lessons from DIY

- Software Configuration Management Patterns, Steve Berczuk with Brad Appleton

- Continuous Integration, Paul Duval

- Continuous Integration on a Dollar a Day, James Shore

- Continuous Delivery, Dave Farley and Jez Humble

- The Art of Agile Development, James Shore

- Continuous Integration Certification, Martin Fowler

The Series

The Practices That Make Continuous Integration series:

- Team working for Continuous Integration

- Coding for Continuous Integration

- Building for Continuous Integration

- Make the Build Self-Testing

- Push Every Day

- Trigger the Build on Every Push

- Fix a Broken Build within 10 Minutes

- Have Reliable Tests

- Broadcast the Codebase’s Health

Definitions

Commit

In the context of Distributed Version Control Systems (DVCS), when I say commit I honestly mean commit-and-push.

Mainline

The Mainline is the line of development in Version Control which is the reference from which system builds are created that feed into a deployment pipeline.

For CVS and SubVersion, this is trunk. For Git, this is the remote main branch. For Mercurial, this is the remote default branch.

Commit Build

The Commit Build is a build performed during the first stage of the Deployment Pipeline or the central build server. It involves checking out the latest sources from Mainline and at minimum compiling the sources, running a set of Commit Tests, and building a binary artefact for deployment.

Commit Tests

The Commit Tests comprise all of the Unit Tests along with a small simple smoke test suite executed during the Commit Build. This smoke test suite includes a few simple Integration and Acceptance Tests deemed important enough to get early feedback.

Lead Time

From Monday.com and Wikipedia: the “latency” (time interval) between the start and completion of a certain task.

It is most often used in Manufacturing and Supply Chain. Yet, it is applicable to all product-based businesses including the business of software.

In IT, lead time is the time between receiving a user request, prioritising it, designing, implementing and getting it released into the hands of the users in production.

For IT delivery, lead time is often limited to the time between committing code into a Version Control System and getting that code into the hands of the users in production.