In part 1 - Team Working for Continuous Integration we looked into the team practices that make Continuous Integration. In part 2 - Coding for Continuous Integration we explored the engineering practices for Continuous Integration. In this last part, we investigate the required practices for a team to succeed with Continuous Integration, i.e. which are the building practices and how to improve builds to support the team practices - especially Agree as a Team to Never Break the Build - and the coding practices - in particular Make Changes in Small Increments and Commit Frequently.

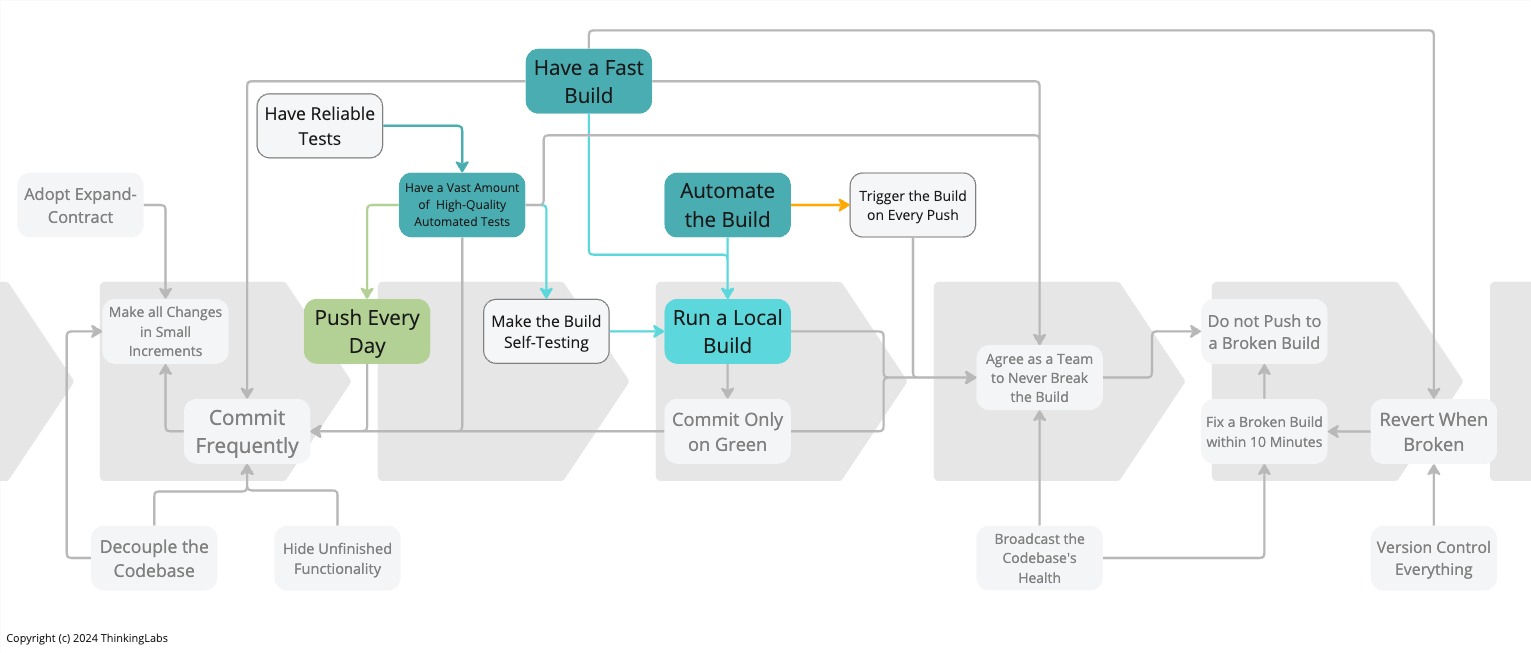

Update Sept 12, 2024: Add the infographic.

Practice 11: Automate the Build

To make things clear, right from the start, this is not about having a centralised build server. Though a centralised build server is helpful, it is not essential to attaining Continuous Integration. Unfortunately, it is common for teams to think that because they have a centralised build server, they practice Continuous Integration. It might be they do. However, from what I have seen (which is still a quite limited dataset), often they do not.

That said, it should be possible for every new team member to check out the code from Version Control, build the application and run all automated tests using a single command from the command-line, i.e. the build script.

The Commit Build on the centralised build server will use that same build script. Conceivably, the commit build might perform a few extra actions not included in the build script such as uploading the build artefact to an artefact repository.

The build script is treated the same way as the production code. It is versioned, tested and constantly refactored. The same design principles (e.g. Simple Design, Single Responsibility Principle, abstractions, small files, small methods, …) apply to the build script to keep it simple and easy to understand.

The build script ensures a deterministic, repeatable, consistent and reliable build that can be executed over and over again without any side effects. It is idempotent.

The build script needs to produce a single unambiguous result: it is either SUCCESS or FAILURE.

Finally, the build script is a prerequisite to Run a Local Build, a required practice to prevent broken builds and keep the software always working. In the end, it increases productivity. Accordingly, it increases throughput of the IT delivery process and contracts time to market. Incidentally, it also improves team morale and drives down burnout.

This is the second of two practices effectively requiring a tool, the build script, to implement the practice. We can argue whether a build script is a tool. At least, to implement the build script we need a tool like a shell, Make, CMake, Rake, Gradle, NPM, Leiningen, SBT, … The other practice that expects tooling is Version Control Everything which introduces the Version Control System including Git, Mercurial, Bazaar, Perforce, SubVersion, CVS, …

Practice 12: Run a Local Build

To perform on-demand production releases at any given moment in time requires having an always-working software application. This means, Agree As a Team To Never Break The Build. As a consequence, everyone in the team has to run a local private build before committing into Mainline.

Running a Local Build means:

- refreshing the local workspace by pulling the latest changes from Mainline and merging these into the local workspace,

- executing the build script,

- when the build script says SUCCESS, we are ready to commit into Mainline.

The Local Build is identical to the Commit Build performed by the Deployment Pipeline or the central build server, except for some additional actions only performed by the Commit Build in particular uploading build artefacts.

It integrates the local work with the work all other team members made available on Mainline. It will detect any conflicts between local changes and remote changes. Not doing so will defer this conflict detection to the Commit Build. Which might introduce a broken build and violate Agree As a Team To Never Break The Build. Inevitably, this hampers the team, impacting the IT delivery throughput and expanding the time to market.

Ideally, we can run the Local Build offline without needing any Internet connection, besides some initial caching of required dependencies. Being able to run the Local Build offline gives engineers more flexibility. Engineers can build on the go while, for instance, being on a train, a plane or simply in the park. That enables engineers to work from anywhere while still being able to commit (assuming a Distributed Version Control System is used) and still receiving build feedback. But more importantly, if the build can be performed without Internet connection, there will be no network latency during the build. Unavoidably, this results in a faster build which in turn enables Have a Fast Build.

All too often, team members do not want to run a Local Build because it is seen as a waste of time (read the build is too slow). They prefer to commit, push, forget and switch to a new task hoping that in the meantime the central build will pass. Using this strategy, teams heavily rely on a central build server to detect integration problems. This way of working comes with many drawbacks. Integration problems are only detected late in the process, delaying feedback. If the build fails due to integration problems it creates context switching. The team member that triggered the build has to pause the new task they started. This also comes with increased work in progress which is inventory, money stuck in the system and comes with a myriad of other problems.

Upon committing, the Commit Build gets triggered. The code will again get compiled and Commit Tests get re-executed.

This might sound like a waste of time and waste of compute time. We are, in the end, building twice: once local and once remote. However, we gain essential early feedback on whether our changes integrate well with the changes of team members. This is economically more valuable as it reduces late rework and enables the fast flow of work. As such, it reduces time to market.

The team member that triggers the Commit Build, should monitor the build’s progress and not start any new task until the Commit Tests pass successfully. Only when the Commit Build is successful can the team member pick up a new task. Monitoring the Commit Build is a critical practice to fulfil the Stop starting, Start finishing-principle to keep work in progress and context switching at minimal levels. Both will ensure higher levels of delivery throughput.

Run a Local Build and monitor the Commit Build before moving on are strong arguments for Have a Fast Build to optimise engineering time, avoid increased work in progress and context switching.

Practice 13: Have A Vast Amount of High-Quality Automated Tests

If we do not have an automated test suite, the only information we get from running the build is whether the code compiles and whether a binary artefact was created for deployment. We do not receive any feedback on whether a change broke the application or not.

Remember, the purpose of Continuous Integration is to ensure always working software and receiving feedback within minutes on whether a change broke the application or not.

In that case, the only way of knowing if the application still works is by relying on time-consuming, repetitive, dull manual regression testing. Note, I am assuming here a modern team where testing happens by everyone in the team, not only by Test Engineers. So, it is a waste of time, energy and the value of every one in the team. It might even introduce burnout due to either boring work or being pressured to execute manual testing within an impossible time frame.

Because we now depend on time-consuming manual testing, we cannot Commit Frequently anymore into Mainline. As a consequence, we are starting to batch up work. From Lean Manufacturing, we know that big batches expand work in progress, drive down throughput and increase time to market. Also, on-demand production releases are not possible anymore, reducing throughput even more.

To gain confidence we are not breaking any existing functionality while committing extremely frequently into Mainline, we want:

- to have enough automated tests to receive ample feedback on whether the behaviour has been changed (in an intended way or not), for that reason, we want many of them, but they still need to be fast;

- and when automated tests pass, they give us enough certainty that we have not introduced a breaking change, on that account they need to be of high quality. Yet, watch out for tests that always pass regardless of changes, or tests that do not test what they promised to test or tests that do not give sufficient clear output to diagnose what changed or does not work.

Then again, it is perfectly fine to delete automated tests when they do not serve anymore as adequate change detectors or never did in the first place.

Having said that, I want to be very clear here. These vast amounts of automated tests are not here to eliminate Test Engineers. On the contrary, Test Engineers will be of enormous value in improving the team’s testing skills and as such enabling the team to build quality in right from the start as well as thinking of risks. Test Engineers can contribute in all sorts of ways: in defining the required acceptance criteria but also in designing and architecting tests, along with programming tests and generating test data. Ultimately, they will allow the team to explore the system’s behaviour in so many more ways.

As Seb Rose appropriately remarked, if we have lots of tests, does that automatically mean we have the right tests? Obviously, no. Many tests do not mean high-quality tests. It could be we have lots of tests but little feedback because they test the wrong things. Or we have few tests but excellent feedback because they test the precise right things. A good mix of roles (Product Manager, Test Engineers, Software Engineers, Operations Engineers, UX Designers) together with Example Mapping should ensure the correct things get tested.

When implementing automated tests, we should consider 3 types of tests:

- Unit Tests: These should be the largest part of the automated test suite. We are speaking 100s or 1000s of them. They should run in less than 30 seconds. Each test should take milliseconds. They should not talk to the database, filesystem or over the network. A test that takes seconds is a red flag and requires immediate attention. Note, this applies to backend code as well frontend code!

- Integration Tests: They should test the Adapters (from Ports and Adapters). These may hit the database, file systems and other systems. They will take longer to run, so we want to limit these.

- Automated Acceptance Tests: They test the application in isolation, without third party integrations, but with a database and a front-end as if it was a user using the application. Often these are implemented using Behaviour-Driven Development techniques. We should have 100s of them. Their total execution time is less than ten minutes. The ten minutes constraint nudges to make these tests efficient through test case isolation and parallelisation as well as improved code execution performance.

Going the extra mile towards Continuous Delivery, we would also have Smoke Tests. These are a restricted set, usually one to five, of end-to-end tests, i.e. including third-party services, executing our most important transactions to check everything works as expected right after deploying a new release. They take less than five minutes.

Note how each of these different kinds of tests have different levels of granularity. Unit Tests have a low granularity. They execute a limited amount of code. As a result, they are faster. Thus, we can have many of them. Also, because they exercise a limited amount of code, we can more easily reason about them. They have a reduced cognitive load. On the other hand, Acceptance Tests have a high granularity. They execute more code and more of the application. In doing so, they are slower. Therefore, we should have fewer of them.

The above is mostly influenced by the Testing Pyramid. Not everyone is happy with that metaphor, especially in the Testing Community. But, in my humble opinion, the Testing Pyramid has the benefit of giving us an indication in which order tests should be executed. At the bottom, we have the fast Unit Tests. We execute these first in an attempt to receive fast feedback. The feedback is nevertheless not perfect. Numerous issues are still missed. As we go up the pyramid, tests are taking longer and executing more code and more of the application but giving us more precise feedback. To improve the feedback of our fast Unit Tests, each time a longer-running Acceptance Test fails, we try to reproduce the problem with a new Unit Test. This ensures next time the problem is covered by a fast Unit Test that is executed first. As a consequence, we receive earlier feedback. But also, the feedback from these Unit Tests becomes more and more precise and more valuable. Lastly, at the top of the pyramid, we have the Exploratory Tests. Often, they are manual but can be assisted by automation. They typically take longer to execute. Despite that, we surely do not want to eliminate them because they generate a lot of feedback value. Automated tests generally only check what we know about the system. Though, we can use automated tests to falsify hypotheses like in the case of Property Based Testing. That said, Exploratory Testing searches for what we do not know about the system. These newly discovered unknowns, which now became knowns, can now feed into new automated tests. Hence, we are improving the quality of our tests.

During the Local Build and Commit Build only Unit Tests are executed together with a small straightforward smoke test suite. This smoke test suite performs a few simple Integration Tests and Acceptance Tests to make sure the most commonly used features are not broken. This set of tests is what we call the Commit Tests.

To commit frequently into Mainline, we need to run these tests repeatedly. Therefore, the Commit Tests should be expeditious. The rest of the Integration Tests and the Automated Acceptance Tests will run in later build stages of the Deployment Pipeline on the central build server.

Practice 14: Have a Fast Build

If everyone in the team wants to commit multiple times per day into Mainline, the Local Build has to be prompt. To prevent breaking the build, we need to execute this Local Build before committing into Mainline.

When the build is slow, two things may happen:

-

Either people tend to not execute the Local Build before committing to Mainline.

From then on, we run the risk of introducing regressions and having a broken build for an extended period. In turn, this prevents on-demand production releases to happen. Consequently, this impacts the delivery throughput and time to market.

-

Or people tend to execute the build less often.

From that time, we introduce batch work. When we build less often, we will commit less frequently into Mainline as we are supposed to only commit after running a successful Local Build and having all tests green.

This batch work initiates larger changesets. Larger changesets introduce higher risks because our build will have to process a large change. If the build happens to break, finding the root cause will take a far longer time. That being the case, we run the risk of having a broken build for a prolonged time. As such, we have lost the monitoring of the health of our application code. This unavoidably impacts the quality of the software. From now on, we lost the ability to perform on-demand production releases, which again lowers the throughput and extends the time to market.

Batch work also delays feedback. Delaying feedback drives down quality. Bad quality will impact the use of software engineering time to introduce new changes. Again this downscales throughput and prolongs time to market.

But what is a fast build?

Twenty years ago Extreme Programming suggested the build should take no longer than ten minutes.

Dave Farley advises in Optimising Continuous Delivery we keep the Commit Build under five minutes.

To conclude, ten minutes is the limit, everything under five minutes is better, 30 seconds is … plain bonus for engineers, though some engineers have an even higher standard …

One of the FogBugz developers complained that compiling was pretty slow (about 30 seconds), which was leading to a lot of sword fights in the hallway.

– Joel Spolsky, Solid State Disks, 2009

Having said that, we have to take into account that every integration takes two builds: one local and one central commit stage build. Because of Agree as a Team to Never Break the Build we should wait for the central Commit Build to be successful before moving. So, when a build takes ten minutes, an engineer has to wait for 20 minutes in total. This is one more reason to keep the build short.

Have a Fast Build seems to contradict with Have a Vast Amount of High-Quality Automated Tests. The first thing to consider is to make tests run faster. Second, we should think of removing old, obsolete tests that have no value any more from the test suite. Many times, teams are afraid to remove tests because of the Sunk Cost Fallacy and the Endowment Effect. They just keep adding. Third, at some point, we will need to split the tests into several stages. We first run the fastest tests during the Commit Build. Longer running tests are executed later. Fourth, we may perhaps think of optimising the automated acceptance tests by attacking the underlying API instead of the UI. In that case, the UI testing should happen with a stubbed backend. Lastly, later, we might need to optimise the test execution even further.

At last, the faster our build is, the easier we can fix a broken build. If a build takes more than ten minutes, we cannot satisfy one of the preconditions for Continuous Integration: fix a broken build within ten minutes.

Conclusion

At first, these building practices do not seem important. In the end, this is just about building, this is just machine time. But, in truth, they are undoubtedly important.

The building practices support both the Team Working and Coding practices that enable Continuous Integration. Failing to implement these building practices will surely fail to implement the other practices and therefore fail to reach Continuous Integration.

This article closes this series on the Practices that Make Continuous Integration. As we can see, Continuous Integration is really not a tooling problem.

Many practices are involved in realising Continuous Integration. Each practice is valuable. Each practice is on its own an enabler of Continuous Integration. But no single practice exists on its own. They are all tangled.

Because each practice amplifies the benefits of the others it becomes challenging to select which practice to adopt first and which practice to adopt next. Selecting the practices to adopt first depends on the unique context and circumstances of our team. Hence, we should use a Continuous Improvement framework, like the Improvement Kata, that takes this context into account to kick-start a Continuous Integration program.

Because of all the benefits put forward in each and every practice, adopting Continuous Integration will improve quality and throughput of IT changes. Dr Nicole Forsgren and Jez Humble confirmed this in their 2016 peer-reviewed academic paper The Role of Continuous Delivery in IT and Organisational Performance that Continuous Integration together with Trunk-Based Development are statistically significant predictors for adopting Continuous Delivery. In turn, Continuous Delivery predicts higher IT delivery performance. Together with adopting Lean Product Management and a Generative Organisational Culture, they predict higher organisational performance, i.e. generating more money.

To conclude, if we want to be ahead of our competition, not adopting these practices is just not an option.

Acknowledgments

Again, a big thank you goes to Lisi Hocke, Seb Rose and Steve Smith for their rigorous review.

Bibliography

- Software Configuration Management Patterns, Steve Berczuk with Brad Appleton

- Continuous Delivery book, Jez Humble and Dave Farley

- Continuous Integration book, Paul Duval

- Acceptance Testing for Continuous Delivery, Dave Farley

- Eviscerating the Test Automation Pyramid, Seb Rose

- The Role of Continuous Delivery in IT and Organizational Performance, Dr Nicole Forsgren and Jez Humble

- Feature Branching is Evil, Thierry de Pauw

The Series

The Practices That Make Continuous Integration series:

- Team working for Continuous Integration

- Coding for Continuous Integration

- Building for Continuous Integration

- Make the Build Self-Testing

- Push Every Day

- Trigger the Build on Every Push

- Fix a Broken Build within 10 Minutes

- Have Reliable Tests

- Broadcast the Codebase’s Health

Definitions

Commit

In the context of Distributed Version Control Systems (DVCS), when I say commit I honestly mean commit-and-push.

Mainline

The Mainline is the line of development in Version Control which is the reference from which system builds are created that feed into a deployment pipeline.

For CVS and SubVersion, this is trunk. For Git, this is the remote main branch. For Mercurial, this is the remote default branch.

Commit Build

The Commit Build is a build performed during the first stage of the Deployment Pipeline or the central build server. It involves checking out the latest sources from Mainline and at minimum compiling the sources, running a set of Commit Tests, and building a binary artefact for deployment.

Commit Tests

The Commit Tests comprise all of the Unit Tests along with a small simple smoke test suite executed during the Commit Build. This smoke test suite includes a few simple Integration and Acceptance Tests deemed important enough to get early feedback.