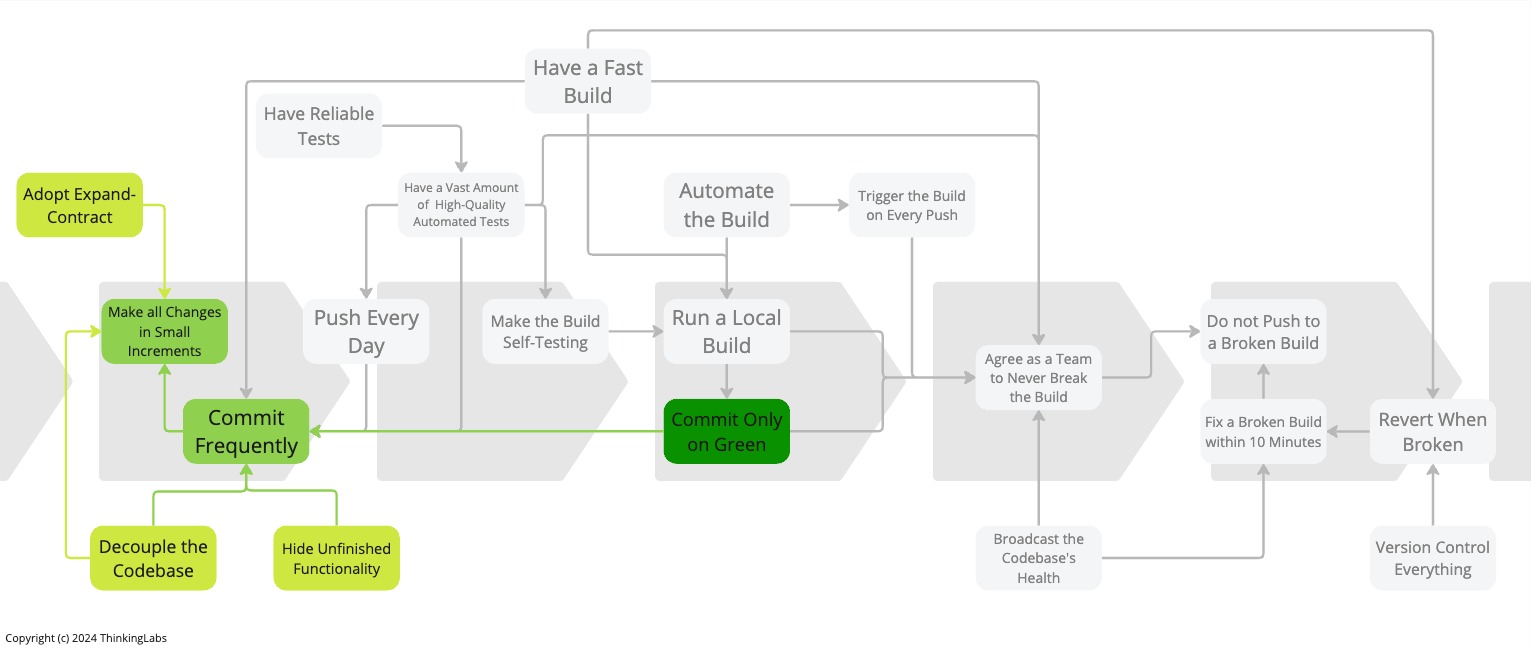

In part 1 - Team Working for Continuous Integration we looked at all the necessary practices to achieve team work around Continuous Integration. Now, we investigate the critical engineering practices individuals, pairs or ensembles should adopt to attain Continuous Integration as a team.

Update Sept 12, 2024: Add the infographic.

Practice 5: Make All Changes In Small Increments

Break large changes into a series of small incremental changes that keep tests passing and do not break existing functionality.

In Growing Object-Oriented Software Guided by Tests, Steve Freeman and Nat Pryce make this analogy with surgery: Surgeons prefer keyhole surgery over opening a patient’s body because it is less invasive and cheaper.

For the same reasons, we prefer to work in small, incremental steps because it is less invasive. We are not ripping apart the application. Therefore it is cheaper because we keep the application always working. We can perform on-demand production releases of the application at any given moment in time because the application is always releasable.

When releases are only happening every month, or every three, six months or once a year, features are pilling up until they finally get deployed into production and released to the users. This pile of features is, as a matter of fact, nothing more than Inventory, similar to manufacturing inventories. With this exception that in manufacturing it is quite easy to see Inventory. Just look around on the work floor for stuff piling up. However, in the software industry, Inventory is far less visible. But it does not mean Inventory is costless for the software industry. On the contrary, it is still money stuck in the system. It is stuck because that money was invested in creating software that we intend to sell. As long as it is not released, that investment does not generate revenue for the organisation.

Accordingly, if we can release any time, we are not pilling up features waiting to be released. Thus, we do not create Inventory. As a consequence, delivery is cheaper.

Because we can release more frequently, we are not holding up changes until a feature is deemed complete. No, we deploy bits of features piecemeal into production. Hence, we receive early feedback on how these changes behave and adapt accordingly. For this reason, we also drive down the Cost of Delay. Again, that makes the delivery cheaper.

Because we are now releasing smaller bits and pieces into the wild, it also becomes far less risky, because the changesets are smaller.

Though, that is hard work. We are continuously solving the hard problem of keeping the application working as we go instead of having to solve this at the end when it is time to release. But it pays off. We can stop at any time. We prevent the sunk cost involved in getting halfway through a big change and then having to abandon it.

This practice applies to all code required for releasing a software system. It applies to production code, as well as to test code, database schema evolutions, application and system configuration and along with infrastructure code.

Make All Changes in Small Increments together with Agree As a Team To Never Break the Build are the two most crucial but also the two most valuable practices to adopt. Yet, from my humble experience, it seems Make All Changes in Small Increments is also the toughest practice to adopt.

Practice 6: Commit Frequently

The central premise of Continuous Integration is integrating early and often on Mainline. This requires frequent commits into Mainline.

When not committing frequently, integrating code becomes time-consuming, vastly non-deterministic and varies wildly in duration. As a consequence, this will slow down the IT delivery Throughput and time to market.

When not committing frequently, this also prevents the communication of changes inside the team. This results in blocking team members to use the latest changes. Again, this will inevitably hurt quality and IT delivery throughput.

As a corollary, to commit frequently we absolutely need to Make All Changes in Small Increments, Have a Fast Build, Have a Decoupled Codebase andHide Unfinished Functionality. If we do not adopt all of these practices, committing frequently will be complicated, if not impossible.

Because we commit more frequently, changes become smaller. We can now work in smaller increments. Merge conflicts and broken builds become less likely.

If a broken build happens, reverting a small change becomes easier than having to revert a big chunk of changes. Reverting now also takes less time, therefore reducing the timespan for a broken build.

Because we commit more frequently, we now feel a gentle pressure to speed up the build even more, keep the codebase even more decoupled, work in even smaller steps and look for ways to hide unfinished functionality which in turn will again allow us to work in smaller increments. Leading to a virtuous circle of improvements.

Practice 7: Commit Only on Green

To keep our application always working at any given time, we may only commit on green. This means, we only commit when the Local Build says SUCCESS which also involves all tests being green.

On the other hand, when committing on red, we violate one of the two paramount practices: Agree As a Team To Never Break The Build. Once we violate this practice, we lose the ability to reach Continuous Integration as a team. On top of that, we lose the ability to release an increment. All things considered, this means the team does not come close to a single-piece flow. We learned from Lean Manufacturing this comes with an increased lead time and time to market.

This is where Test Driven Development (TDD) supports Continuous Integration. We start by writing a failing test. We implement as little production code as required to get the test passing to green. When the tests are green, we commit into Mainline. Then we refactor. If the test is red, we revert. When the test is green again, we commit again into Mainline.

Thus, TDD creates this commit cadence that satisfies Commit Frequently and that is required to accomplish a state of Continuous Integration.

That said, even when not following Test Driven Development, it is possible and still vital to satisfy Commit Only on Green. But … we will have less confidence because we are moving forward in the dark. For sure, we will move slower. Again, this involves long lead times and increased time to market. What is more, our design will not be as good as when we practice Test Driven Development. The importance of Test Driven Development is not the tests, it is to force the code into good design and write testable code. Test Driven Development is a design tool, not a testing tool.

Practice 8: Decouple the Codebase

To work in small increments, we definitely need a decoupled codebase.

When a codebase is too coupled, it is arduous to adopt incremental software engineering skills. Any change will ripple through the whole codebase, ripping apart the application and preventing the application from working all the time. Again, we incur a sunk cost because we cannot release what we have already implemented for a long time.

That is why adopting patterns like Ports and Adapters (aka Hexagonal Architecture) together with Simple Design and intentional code duplication (code, not concept duplication) are so important. These design principles help us in getting a decoupled codebase. Consequently, this leads to a more maintainable codebase and even more crucial: simple code that fits in our head.

From my humble experience, having small classes, small methods, and applying the Single Responsibility Principle together with Dependency Injection Principle already brings us a long way forward.

It is generally accepted that adopting these software design principles is beneficial for quality. Interestingly, it also optimises the required engineering time to introduce new changes, hence reducing the time and effort spent. As such, it also reduces Operational Expenses.

A decoupled code base also allows for teams or even pairs inside teams to move forward independently. Hence, fewer changes are stuck waiting for other changes to finish. Therefore, teams spent less time on changes.

As a result, it drives down the lead time for changes, reducing the time to market and increasing the Throughput of the IT delivery process.

Because we spent less time on changes, we have a smaller Inventory of unfinished functionality. Together with the reduced Operational Expenses, it reduces the money spent on changes.

Having a Decoupled codebase not only improves quality, but it also improves all three Theory of Constraints metrics: we increase Throughput, while simultaneously reducing Inventory and reducing Operational Expenses. This leads to more money generated for the organisation.

Practice 9: Adopt Expand-Contract

Expand-Contract seems to be a forgotten pattern in the IT industry. It is a little unknown gem. Though, it is unquestionably a strong enabler for Continuous Integration.

If we have to perform a large-scale refactoring that could rip apart our application for a long time, preventing on-demand production releases.

For instance, let us say we want to change the signature of a method. But, that method is used at 42 places in our codebase. Changing that signature together with all consumers in one go can take fairly long. During that time our application is broken. It is ripped apart. It does not work anymore. We cannot release the application into production at any time anymore.

To avoid breaking the build, many teams tend to use the classic approach with Branch by Version Control, i.e. create a branch in version control. However, this approach introduces the problem of hiding the change from the rest of the team. The change only becomes visible the minute the branch gets merged back into Mainline when the refactoring is finished. During that time, team members may have continued to add additional consumers for the old method signature. At merge time, this may create the necessary merge conflicts and rework. Performing that refactoring then becomes an especially time-consuming and hugely unpredictable activity. In addition, at merge time, it may also halt the delivery of all ongoing new functionality. Because everyone in the team needs to integrate that change that was not known before into all ongoing work. All of this will again increase the lead time for the refactoring, reduce the Throughput and slow down the time to market.

Instead of using Branch by Version Control, we should adopt Expand-Contract.

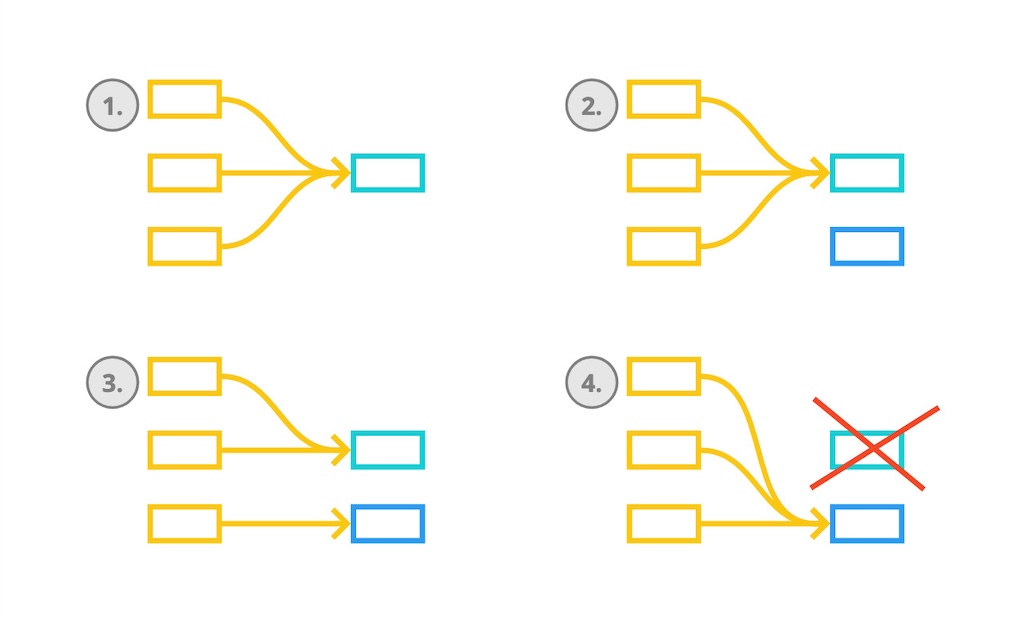

Expand-Contract works as follows. (1) We start from a situation where a method is called at various places in the code base. Instead of changing the method signature and breaking the codebase, we duplicate the method and apply that signature change to the duplicated method.

(2) Now we have two methods: the old one with the old signature called from 42 places in the codebase and the new one with the new signature that is nowhere used in the codebase. At this point, we mark the old method as deprecated and we commit. This is called the Expand phase. We expanded the codebase with a new method having the new method signature.

It is a good practice to also verbally communicate to the rest of the team that a new method exists and that everyone should start using that new method. Now, the rest of the team is aware they should use that new method. Moreover, the team can, in effect, start using that new method immediately. At this point, we can still release the software into production.

(3) Next, we will gradually move consumers to use the new method signature. On each consumer move, we can commit and we can again still release the software into production.

(4) Once all consumers call the new method signature and the old method with the old signature is nowhere called anymore, we can remove the old method. This is called the Contract phase. We contracted the codebase by removing the old method. Again, we did not break the codebase because there were no consumers left using the old method signature. Again, we can release it into production at any given moment.

Evolutionary database changes use Expand-Contract extensively to rename columns, rename tables, split columns into two columns, and move columns, …

When introducing a v2 API alongside a v1 with different URLs we also make use of Expand-Contract.

Blue-Green Deployments is Expand-Contract for deployments. We expand by adding a new version in production (blue) next to the old version (green). We keep blue and green running until blue is deemed good. We contract by removing green.

Many breaking infrastructure changes are implemented with zero downtime using Expand-Contract.

In Make large scale changes incrementally Jez Humble reported how ThoughtWorks’ GoCD moved incrementally from using Velocity and JsTemplate as User Interface technology to using Ruby on Rails on the JVM. Jez calls this Branch by Abstraction, a technique introduced by Paul Hammant in his original article on the technique. In my humble opinion, what GoCD did was Expand-Contract.

I would say Branch by Abstraction is a special kind of Expand-Contract. The difference lies in the use of an abstraction layer to cut away the time-consuming refactoring.

We use this technique, for instance, to replace an algorithm with a more performant algorithm. Or to replace a library used everywhere in the codebase with a different library. For instance, we want to replace our Object Relational Mapping (ORM) library with another one or, let us be wild, with plain old SQL.

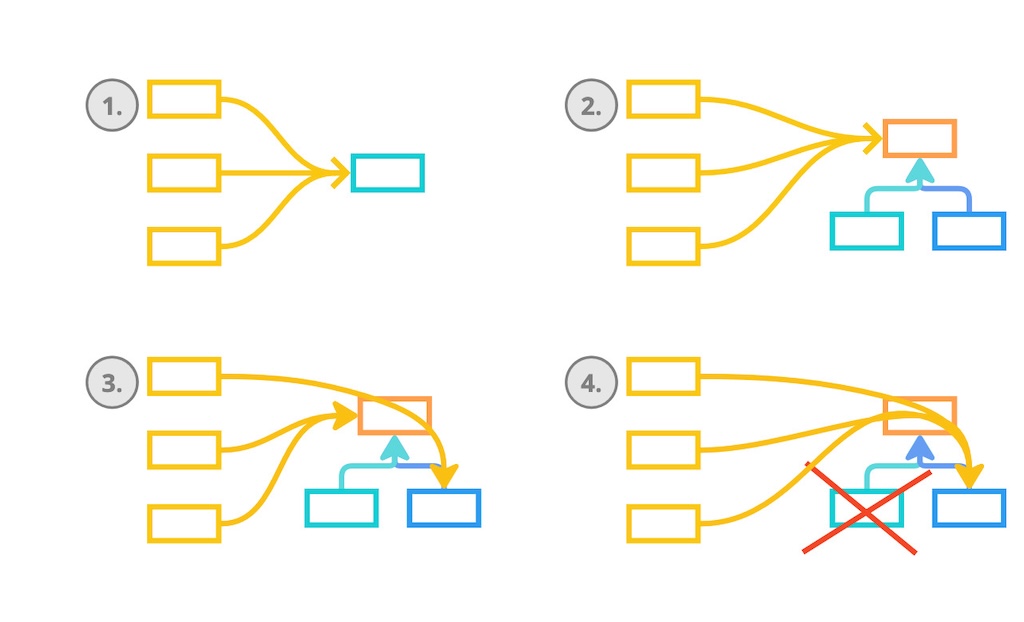

Branch by Abstraction works as follows. We begin with a situation where various parts of the software are calling some supplier code (the algorithm or the library we want to replace).

First, we start by introducing an abstraction layer in front of the supplier code we want to replace. In most programming languages that would be an interface or an abstract class.

Next, we gradually move all client code to use that new abstraction layer.

In the meantime, we start a new implementation for that abstraction layer that uses the new supplier code (that new more performant algorithm or that new library).

Lastly, we now gradually swap out the old supplier code until all client code uses the new supplier code.

To summarise, Expand-Contract and Branch by Abstraction allow us to perform refactorings that take weeks or months to execute while keeping the application always working. Allowing us to perform on-demand production releases at any given moment in time and still be able to add new functionality while the refactoring is ongoing. We are never blocking the flow of work through the value stream. We are never blocking the delivery of new functionality. As a result, we are never creating Inventory and thus never keeping money stuck in the system.

Practice 10: Hide Unfinished Functionality

What if a feature takes too long to implement?

Often features take a long time to implement. Most of the time it makes no sense to release a feature incrementally. For that reason, many teams use Branch by Version Control to hide the unfinished functionality. That approach has the downside that we never integrate the feature with the rest of the code during its implementation. The feature only gets integrated with the rest of the codebase once we finish the feature and we merge the branch back into Mainline. During the time the feature is being implemented, we are blind to whether the feature causes any integration problems or not.

Instead of using Branch by Version Control to keep unfinished functionality out of a release, we should just hide the unfinished functionality from the user.

Hide Unfinished Functionality is probably the most straightforward practice to adopt. It is perfectly acceptable to have unfinished functionality sitting in production. It may even be behind a publicly accessible URL as long as it is not discoverable by the users and cannot be misused by malicious actors (e.g. to gain access to the system or learn valuable information about the system). Most of the time we do not need fancy feature toggling to hide unfinished functionality.

For instance, if we are developing a new screen for our User Interface. As long as we have not finished that screen, we do not add a menu entry to the navigation. We only add this at the end, when the screen is completely done. We could say that adding the menu item is kind of flipping a toggle.

The same is true for extending backends. If we are adding a new backend service, we do not add consumers as long as the backend is not yet finished. Or for adding new API endpoints. Simply do not document the endpoint as long as the endpoint is not ready.

Of course, this is not always possible. Sometimes we have to modify a widget inside an existing screen. Or we have to change the behaviour of an existing backend service. This is when Feature Toggles are required.

Feature Toggles give great flexibility. Toggles are an enabler for Operability and Resilience. But …

Be careful! With great power comes great responsibility. Feature Toggles can be extremely dangerous when done badly. It is tremendously easy to shoot oneself in the foot and introduce lots of technical debt with toggles.

Badly managed toggles can backfire horribly! Like we learned from the Knight Capital Group case. Knight Capital Group was a financial services firm. In 2012, Knight was the largest trader in U.S. equities with a market share of around 17 percent on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) as well as on the Nasdaq Stock Market. They managed to lose 440 million USD in 45 minutes. Because they repurposed an existing feature toggle between two releases giving the toggle a different meaning together with manual deployments on eight servers. However, they forget to deploy the new release on one of the eight servers. One server still ran the old application version with a different meaning for the repurposed feature toggle. This resulted in one server sending child orders totally out of control for each incoming parent order. Ouch!

That being the case, we need to manage toggles. Like with Work in Progress, we do not like to have too many active toggles. Whenever we do not need a toggle anymore, we delete it, immediately. Otherwise, we run the risk of having a codebase with quantities of toggles. No one knows wherefore they are used. Hence, no one dared to remove them.

Toggles should not depend on each other. Avoid the situation where to turn a feature on, we have to turn toggle X on, toggle Y off and toggle Z on again. It is extremely difficult to reason about such a situation. It introduces a testing headache (or should I say hangover). As a consequence, always have one feature, one toggle.

Toggles introduce branching logic. Branching logic needs to be tested. Therefore, we have to run our automated tests against our application with both the feature on and off. On the other hand, in most situations, manual exploratory testing should only happen against the next situation that will happen in production. If the toggle will be on in production, exploratory testing should happen with the toggle turned on. But as Lisi Hocke rightfully commented: it depends! If we want to have information about the production situation, yes, manual exploratory testing should happen with the toggle on. However, if we want to know how things behave in the case we turn the toggle off, are there no side effects, then manual exploratory testing should happen with the toggle off.

Branching logic also means introducing code complexity. Code complexity means maintenance burden. There are many ways we can implement a toggle. Not all of them are good. Pete Hodgson suggests in his article Feature Toggles different maintainable implementation techniques.

Conclusion

To gain Continuous Integration, a team has to adopt six software engineering practices where Make All Changes In Small Increments has a central place. It instils the five other practices. Each and every one of those five practices is in place to enable incremental software development skills which are vital to get to Continuous Integration.

Acknowledgments

Lisi Hocke, Seb Rose and Steve Smith for their thorough review of the article and their many feedbacks.

Lagavulin for helping me finalising the damned article.

Bibliography

- Growing Object-Oriented Software Guided by Tests, Steve Freeman and Nat Pryce

- Continuous Delivery book, Jez Humble and Dave Farley

- The Goal, Eliyahu Goldratt

- Make Large Scale Changes Incrementally with Branch by Abstraction, Jez Humble

- Parallel Change, Danilo Sato

- Introducing Branch By Abstraction, Paul Hammant

- Branch by Abstraction, Paul Hammant

- Feature Toggles, Pete Hodgson

- The $440 Million Software Error at Knight Capital, Henrico Dolfing

- Feature Branching is Evil, Thierry de Pauw

The Series

The Practices That Make Continuous Integration series:

- Team working for Continuous Integration

- Coding for Continuous Integration

- Building for Continuous Integration

- Make the Build Self-Testing

- Push Every Day

- Trigger the Build on Every Push

- Fix a Broken Build within 10 Minutes

- Have Reliable Tests

- Broadcast the Codebase’s Health

Definitions

Commit

In the context of Distributed Version Control Systems (DVCS), when I say commit I honestly mean commit-and-push.

Mainline

The Mainline is the line of development in Version Control which is the reference from which system builds are created that feed into a deployment pipeline.

For CVS and SubVersion, this is trunk. For Git, this is the remote main branch. For Mercurial, this is the remote default branch.

Lead Time

From Monday.com and Wikipedia: the “latency” (time interval) between the start and completion of a certain task.

It is most often used in Manufacturing and Supply Chain. Yet, it applies to all product-based businesses including the business of software.

In IT, lead time is the time between receiving a user request, prioritising it, designing, implementing and getting it released into the hands of the users in production.

For IT delivery, lead time is often limited to the time between committing code into a Version Control System and getting that code into the hands of the users in production.

Throughput

From Theory of Constraints: the rate at which the system generates money - through sales. The sales part is quite important. If an organisation only produces stuff without selling, it will just go bankrupt.

Inventory

From Theory of Constraints: all the money that the system has invested into purchasing or creating the things it intends to sell.

Operational Expenses

From Theory of Constraints: all the money the system spends in order to turn inventory into throughput.