We are sold on the idea of practising trunk-based development. However, all the articles we read on the topic leave us with tons of questions. This is an attempt to answer these questions. See it as a kind of Trunk-based Development FAQ. I suppose this will be a continual work in progress, as new unanswered questions will arise. If you have an unanswered question, feel free to open a ticket here.

Update Aug 25, 2025: Add the Walking Skeleton to handling large-scale changes.

Update Aug 30, 2025: Add the question “How to maintain multiple versions?”.

Update Aug 30, 2025: Add the question “Can we use branches?”.

- How do we handle large-scale changes?

- How do we handle large-scale refactoring?

- Does the code tree end up duplicating some of the feature concepts?

- How do we handle development vs production vs testing environments?

- Where do people do experiments that may or may not go into production?

- How do we handle interim commits that are more about saving work than about committing for the long term?

- How to combine the version control system as a personal tool with the team tool?

- How to deal with a codebase without any tests?

- How to handle framework upgrades?

- How to maintain multiple versions?

- Can we use branches?

How do we handle large-scale changes?

The point here is incremental software development. Breaking up large changes into a series of small incremental changes. Regardless of how large a feature or change is, it grows small commit by small commit on Mainline. Every small commit is atomic. It keeps the codebase working.

This is hard work. It requires some upfront thinking on how to break down the large change into a series of changes that build upon each other. In some way, it is a form of mini-planning.

Supposing the new feature involves a new screen in the UI that uses a new backend service. We will typically first implement the backend service. As the backend service is not used, we do not need any Feature Toggles to hide the backend service. It can just linger around unfinished, as nobody cares. Once the backend service is ready, we can start implementing the new screen for the frontend. As long as the screen is not completed, we do not wire it into the frontend navigation. Again, we do not need any Feature Toggles to hide the screen. Only when the screen is finished, do we wire it into the navigation. Having said that, a better approach is to practice the Walking Skeleton. We start by implementing just enough backend service, followed by just enough UI that consumes the minimal backend service. The screen is still not finished. So we keep it unwired from navigation. However, even in this case, it will materialise over several commits where the minimal backend is implemented first, and thus kept hidden, followed by just enough UI. Once this Walking Skeleton works, we can grow both the frontend and the backend together. Still, frontend and backend changes can occur in a single commit, but most likely over several commits. We add a little backend followed by a little frontend.

Another strategy is to have two pairs, each implementing the frontend and backend in parallel. In that case, the frontend will work with a mocked backend until the real backend is ready. In this case, also, the frontend screen is not wired into the navigation until the screen is completed. But parallelising work is never a great idea; therefore, the first strategy would be the better option.

How do we handle large-scale refactoring?

The large-scale changes naturally raise the question about large refactorings that can take days, weeks or sometimes even months to complete. Months are not unlikely in infrastructure evolutions.

Let us say, a silly, simplistic example, we have a method that is used at 42 places in the code base. For some valid reason, we have to change the method signature. If we change the signature and all consumers in one go, this will take a fair amount of time during which no integrations happen and thus no feedback.

The classic way of solving that is to use Branch by Version Control. The team creates a version control branch and then performs all the required modifications. However, we run the risk that in the meantime, someone else introduces a new consumer for the old signature.

A better approach is to Adopt Expand-Contract, also known as Expand-Migrate-Contract or Parallel Changes.

When replacing an algorithm with a better, more performant version but that still needs testing in production, or when replacing a library, Branch-by-Abstraction would be the preferred option.

Does the code tree end up duplicating some of the feature concepts?

When modifying a large chunk of code, do you sometimes end up with “old version” and “new version” in the code base, so you can slowly improve the new version, and only flip it on when ready?

The alternative would seem to be, make the single version always able to act like the old and new version, but that seems both hard and brittle. But… lots of code dupes in the tree seem not great, too. You’re basically making branches, but in-tree.

Yes! We do sometimes have both “old version” and “new version” alongside each other. It is not that unusual, as it is the only way to evolve a codebase incrementally without breaking. This happens even more often with infrastructure code. Just renaming a resource already requires duplication.

In reality, it is a documented pattern known as “Expand-Contract” (or expand-migrate-contract) (as explained in the previous question How do we handle large-scale refactoring?).

Indeed, we do introduce a code branch instead of a version control branch. But with the benefit that it is visible to the team. The team sees the impact on their code and can adapt. This is not possible with a version control branch. In that case, the code is hidden from the team.

How do we handle development vs production vs testing environments?

Environments are not handled by the version control system.

In the early 2000s, ClearCase advocated for version control environment branches. To deploy in an environment, code had to be promoted into the respective environment branch, which triggered a deployment in the said environment. This way of working has severe downsides and should not be followed any more.

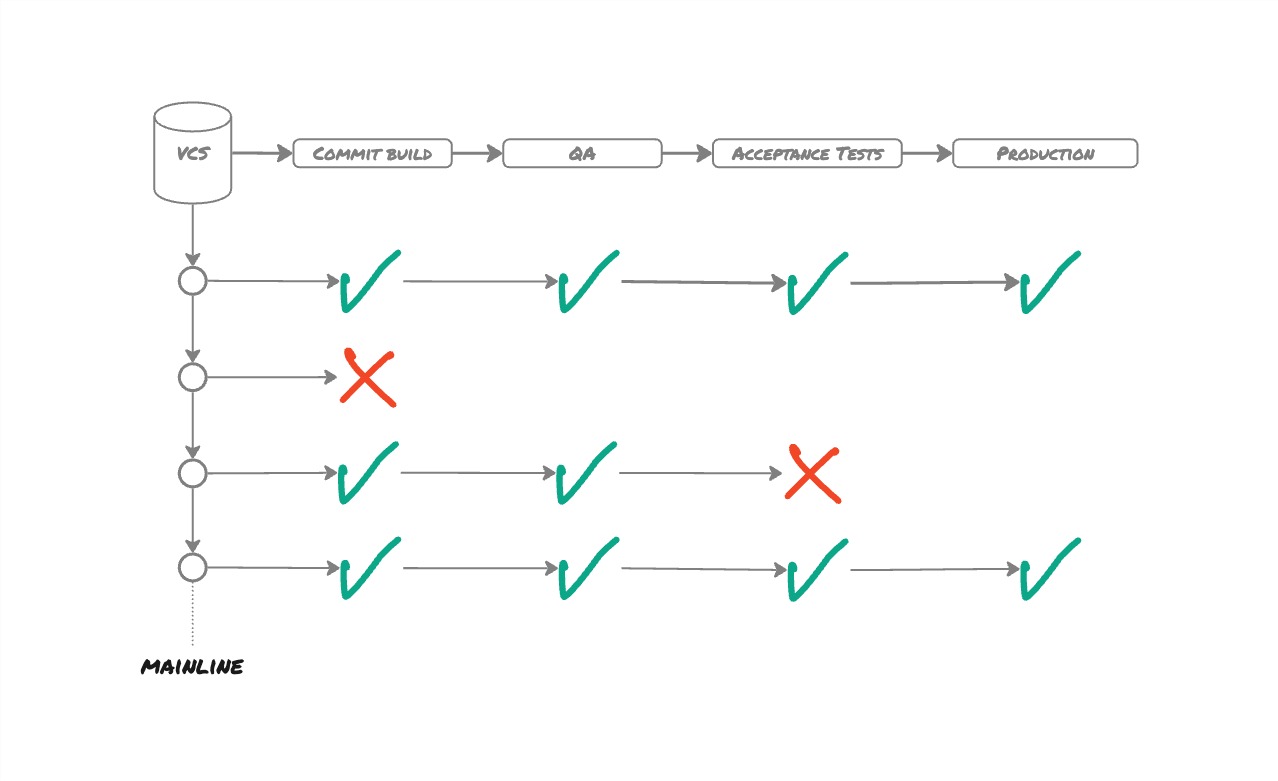

Deployments in the different environments should be handled by the Continuous Delivery Deployment Pipeline.

The Deployment Pipeline consists of several sequential stages. Some stages could be executed in parallel. For instance, load testing and security testing could all happen in parallel with the Automated Acceptance Testing.

The first stage of the pipeline is always the Commit Build (or Commit Stage). It is triggered by any commit on Mainline. The outcome of the Commit Build is a binary build artefact, i.e. a Jar file, a Python PyPi package, a Docker Image, …

Once we have the build artefact, the next stage can deploy it in a testing or QA environment. The following stage can now start executing the Automated Acceptance Tests on the testing environment.

Once all of that is successful, we can decide to deploy to production, which happens in the final stage of the Deployment Pipeline.

Essentially, the Deployment Pipeline builds the build artefact only once and then promotes it from one environment to the other.

This means that all environments receive the same version of the codebase. Variations between environments are handled by configuration, and exceptionally by code branches. We say exceptionally, because environment code branches are difficult to test, so we want to avoid that.

Where do people do experiments that may or may not go into production?

If experiments should go into production, in all evidence they should land on Mainline, likely behind a Feature Toggle to allow turning the experiment on and off.

If the experiment should not go into production, I guess we are more speaking about a Spike, writing throw-away code to test an idea. Such experiments should be sharp and short. At all times, we avoid committing to version control. The minute code lands in version control, it becomes production code. Because of the sunk cost fallacy, it gets particularly hard to throw away the code. This only works for experiments under 24 hours. That is not always possible. Sometimes experiments require more investigation, more collaboration. To save us from landing spike code into production code, we should commit to a “spike” branch that is automatically deleted after 72 hours.

How do we handle interim commits that are more about saving work than about committing for the long term?

I never want to walk away from my desk with code that has not been committed and pushed, so I am never at risk of data loss. But I don’t have the luxury of always guaranteeing I end the day at a good stopping point, which means committing and pushing WIP code.

I guess, in this case, a temporary branch would be acceptable, like for the experiments, just to store the end-of-day work that will be picked up the next day. To avoid this temporary branch from becoming a Feature Branch, the work on that branch should be integrated at the start of the next day with Mainline and the temporary branch destroyed.

Having said that, a better approach is to have atomic commits at all times that leave the codebase in a releasable state. That eliminates the need for a temporary branch, as then we can just push to the remote Mainline at the end of the day.

How to combine the version control system as a personal tool with the team tool?

I am very used to using version control as a personal tool, not just a group tool — I commit individual, incremental chunks that are easy to understand and test in isolation. I regularly look at a diff to see what I’ve changed and check myself. I can’t keep track of huge commits, so I use version control to keep the WIP manageable.

If I’m working against main, it seems like I lose the “personal tool” bits, and only have the group tool — everything is for everyone.

How do you replace the utility version control has for me, before I am ready to share, before work is ready to push?

I know the high level answer is “make smaller commits that always result in green builds”, but… how?

To be honest, it is the first time this aspect has been raised.

But, a version control system is first and foremost a communication tool for the team to communicate changes. In the end, it is a team that delivers working software, not individuals. Hence, the reason for Continuous Integration is to have working software all the time, which enables on-demand production deployments and thus shortens time to market and reduces the cost of delay.

Yet, by times it happens that at the end of the day we do not have working software but we still want to store interim commits. It is not ideal, but human, as long as we are mindful of the exception.

How to deal with a codebase without any tests?

Do you have any advice on how to deal with a codebase without any tests? Is it too risky to use trunk-based development in this context?

We should understand that whether to use branches or trunk-based development, in the case of a codebase without any tests or few tests, does not change much. The situation remains the same. Having a branch likely followed by a code review only gives a sense of risk mitigation and safety, but it will not improve much. A better risk mitigation would be manual testing, which is possible in both cases. Be aware that with trunk-based development, a commit to Mainline does not equal a deploy and release to production. The commit still has to go successfully through the Deployment Pipeline, and thus be promoted over the different environments before landing in production.

In the end, the question is not whether to use branches or not when having no tests. The question is how much risk-appetite the team has and how much willingness to change the situation.

If the team is confident enough, they might choose to go for trunk-based development. It will uncover all the problems and gently nudge the team to adopt the necessary practices to mitigate the risks. That should encourage the team to grow a comprehensive automated test suite. But, the target is not 100% code coverage. 20-30% might be enough if the core, or high-risk part of the codebase, is covered.

If the team is more risk-averse, they might opt for branches together with growing the test suite. However, the problem with branches is that they tend to cover up the problems. It may remove the incentive to do something about the situation. That all depends on the team’s motivation and perseverance.

How to handle framework upgrades?

How would you suggest implementing this methodology when it comes to, say, framework migrations? Can’t have two versions of the framework coexisting at runtime, so how do you achieve this using only incremental changes?

Or upgrades of Java, Ruby, Python, …

Clearly, as we cannot have both versions coexisting in the same codebase, techniques for large-scale refactoring like Expand-Contract will not work.

One option is using a Canary Build. We set up a second build alongside the main build that uses the newer version of the framework or the programming language. For any failure, we try to fix it on Mainline in such a way that it complies with both versions. We manipulate the codebase to be compatible with both versions. Is that easy? No. That will be hard work. But it has the benefit that we never block the flow of work through the value stream. We can keep delivering new functionality while we perform the upgrade in small incremental steps. Obviously, this requires to Have a Vast Amount of High-Quality Automated Tests.

The alternative is either halting all delivery while performing the upgrade on Mainline. Not great, business-wise. If that only takes a week, that could be conceivable. If it takes weeks, it is an outright bad idea. Or using the classic approach with a considerably long-lived branch upon which the upgrade is performed. New deliveries are still possible, but have to be cherry-picked into the branch. That is a substantial additional effort, and mistakes can happen.

How to maintain multiple versions?

Not all code bases are SaaS products. Some code bases are on-premise solutions released following a specific version scheme. Depending on the support model, older versions need to be maintained. How does that work with trunk-based development?

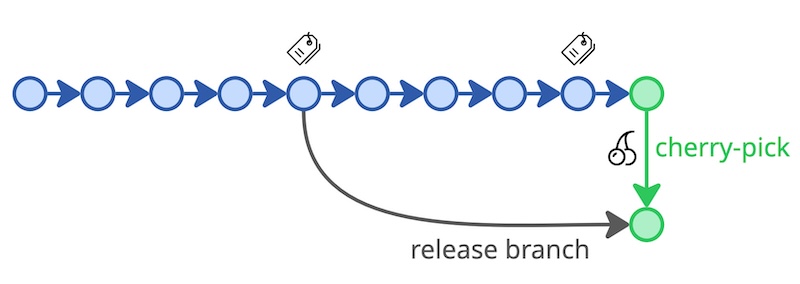

When releasing a version, we tag the code base in Version Control with the version number. In that case, we do not yet create a release branch. We only create the release branch the minute we need to fix the version.

Here is the hint. Fixes do not happen on the release branch. The fixes happen on Mainline and cherry-picked into the release branch. It has the benefit that we do not need to merge the release branch back into Mainline.

On the odd occasion we cannot apply the fix on Mainline because Mainline has diverged too much from the release branch, we have no choice but to perform the fix on the release branch and eventually replicate it on Mainline.

Can we use branches?

The data shows that fewer than three active parallel branches at any time, with very short branch lifetimes, i.e. less than a day, equate trunk-based development (see Accelerate, p55). Essentially, this comes down to practising GitHub Flow but with short-lived branches.

So, yes, according to the data, branches are compatible with trunk-based development, meaning fewer than three, shorter than 24 hours. trunkbaseddevelopment.com also mentions it as one of the three styles of trunk-based development: committing straight to Mainline, short-lived branches, Google’s “Patch Review” system.

However, we start to see in the industry, teams pretending they practice “scaled” trunk-based development. Yet, most of the time, they only apply GitHub Flow while forgetting the part about short-lived branches, which essentially means merging at the end of the day. That is one reason why we are quite persistent in committing straight to Mainline.

Having said that, some branches have their place with trunk-based development:

- spike branches for experimentations.

- release branches when having to maintain various versions of a single code base.

[…] Trunk-based development is great for straightforward changes, mainly when these changes can be split into a sequence of little steps. Feature branches are great for experimental stuff when we don‘t know where the journey will go - or if we even will throw the whole branch away and start over.

You might say: „Then use feature flags/toggles!“. Yes, sometimes. But feature flags also add complexity, […]

– Urs Enzler, Dec 9, 2025

Acknowledgement

Luke Kanies for raising the idea for a kind of Trunk-based Development FAQ.

Steve Hallman for raising the Walking Skeleton.

Related Articles

- On the Benefits of Trunk-based Development

- Continuous Integration! Where to Start?

- Environment Branches harm Quality

Definitions

Mainline

The Mainline is the line of development in Version Control, which is the reference from which system builds are created that feed into a Deployment Pipeline.

For CVS and SubVersion, this is trunk. For Git, this is the remote main branch. For Mercurial, this is the remote default branch.

Commit Build

The Commit Build is a build performed during the first stage of the Deployment Pipeline or the central build server. It involves checking out the latest sources from Mainline and, at a minimum, compiling the sources, running a set of Commit Tests, and building a binary artefact for deployment.

Commit Tests

The Commit Tests comprise all of the Unit Tests along with a small, simple smoke test suite executed during the Commit Build. This smoke test suite includes a few simple Integration and Acceptance Tests deemed important enough to get early feedback.