Environment feature branches were popularised in the 1990s and 2000s by centralised Version Control Systems like ClearCase. Since the 2000s, this practice has become increasingly rare because of the awareness of its costs and more importantly its risks. Yet, some organisations still rely on them resulting in shaggy quality outcomes.

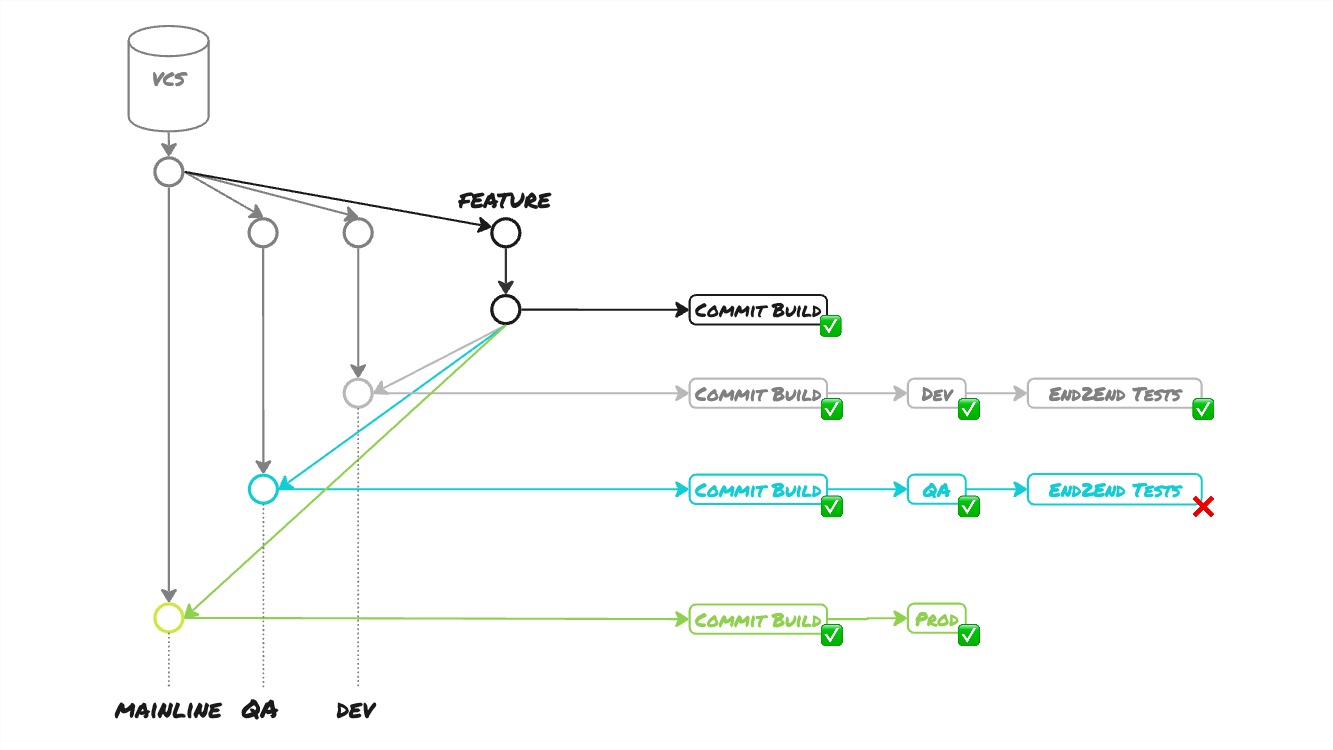

With Environment Branches, the Version Control System promotes changes between environments instead of the Deployment Pipeline. Engineers merge their Feature Branch into the branch that targets the environment where to deploy their changes. Upon merge, a “Deployment Pipeline” is triggered that compiles the code, executes unit tests, builds a binary artefact, and deploys it into the target environment. Depending on the target environment automated End2End Tests get executed.

This way of working involves a couple of obstacles and risks that disable a consistent, reliable, deterministic and repeatable process for releasing a software product.

First, it violates two core Continuous Delivery principles: Always build on foundations known to be sound and Keep the build and test process short. To satisfy these principles requires adopting the practice of Build Only Once.

On each feature branch merge into a subsequent environment branch, a new build is triggered that produces a brand new binary artefact. This means every environment receives a newly built binary artefact. As a result, what gets tested in development is not the same as what gets tested in QA, and is not the same as what gets deployed into production. With every build, we run the risk of introducing subtle differences: different compiler versions, different library versions, different compiler configurations, changes in the toolchain, etc. In a sense, we have no confidence at all whether the thing that gets deployed into production truly works. That is a first risk. This violates the Continuous Delivery principle to Always build on foundations known to be sound. The binary deployed into production should be precisely the same as the one that previously went in prior test environments. Some deployment pipelines validate this by storing hashes of the binary when created and verify the binary is identical at every following stage in the delivery process.

Because we are rebuilding binary artefacts for every environment we transgress a second Continuous Delivery principle to Keep the build and test process short to provide the team with feedback as soon as possible. Recompiling, re-executing unit tests and recreating binary artefacts takes time. The more environments, the more time adds up. This lengthens the release process and increases the delivery lead time. Moreover, from an audit perspective, it is essential to ensure that no changes are introduced, either malicious or by mistake, between creating and releasing the binaries.

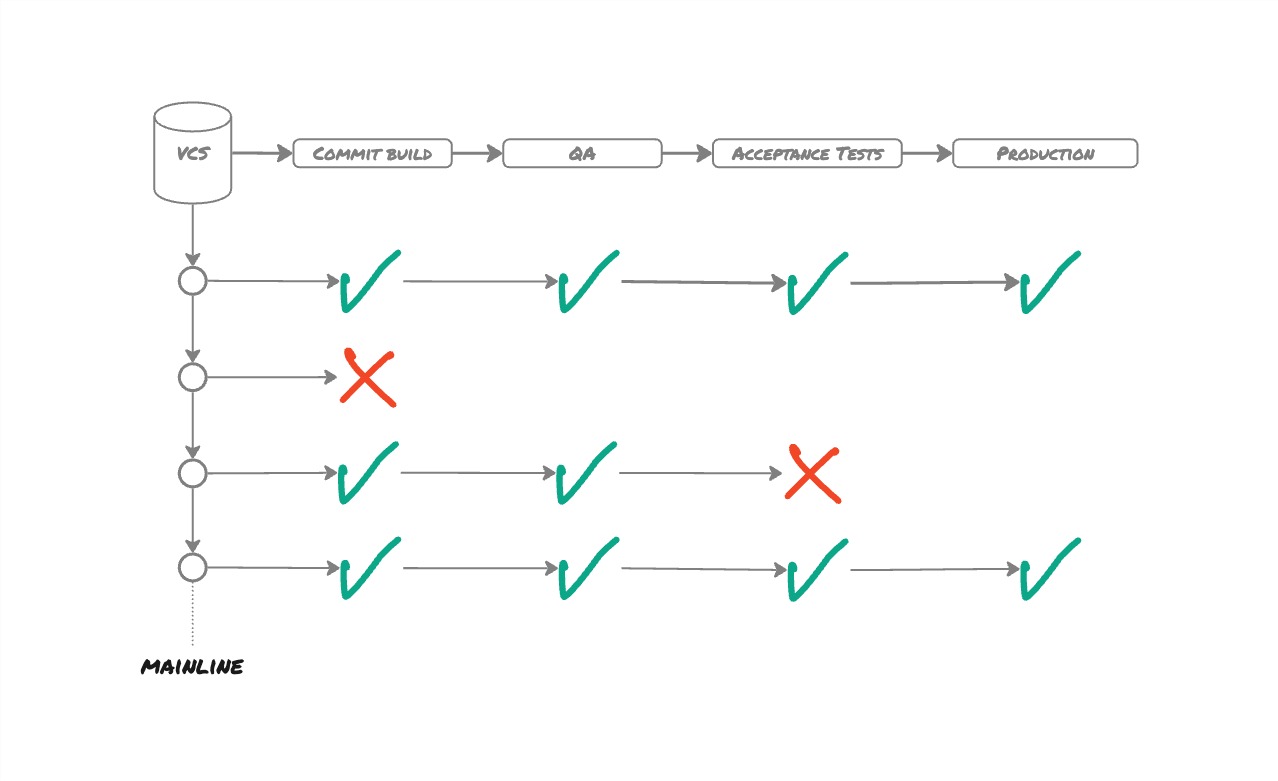

But, there is a bigger problem with this. The delivery process is not hampered by a failing test. As the diagram shows, the automated acceptance tests fail in QA, but the team is not blocked to nonetheless releasing in production despite failing tests. This infringes the practice of Stopping the Line when any part of the delivery process fails. When the line fails, the team owns that failure, drops everything, stops all work and fixes the problem immediately. The team picks up work again only on restoration of the delivery process. Without this practice, there is no incentive to fix failing tests. Failing tests will be left unbothered. Even worse, test failures will stack up over time turning the test suite useless. That is also what happened with that organisation. This is a second risk.

Because we can deploy straight to production with failing tests nothing prevents us from merging a feature branch right into Mainline and deploying to production without prior testing in test environments. This is a third risk.

At any time, anyone can introduce changes in any environment branch resulting in the long-running branches to diverge. Meaning that binary artefacts will diverge even more between environments. Many times it happened that an environment branch had to be recreated from Mainline. That is a fourth risk.

As one can see, the delivery process becomes quickly fairly complex. The build pipeline supporting this includes many exceptions and special cases to cope with the differences and vagaries of the various environments. Such build systems make unnecessarily complex what should be trivial. This forces us into fragile, expensive release processes in which the qualitative outcome is questionable.

Lastly, this practice of environment branches brings an unquestionable fair share of stress and cognitive load for the team.

Naturally, the question raises Is quality important to this organisation? According to me, undeniably no. If it was, different practices would have been established.

The crucial practice to adopt to build quality into the product is the Deployment Pipeline. It is a linear process which is fairly simple to reason about. The commit build produces a binary artefact that gets promoted from one environment to another until it finally arrives in production.

A Deployment Pipeline provides visibility to everyone in the team about the delivery process to improve feedback and create an empowered team. Clearly, with environment branches, that is not the case any more. It is moderately difficult to know which commit is in which environment, even less which feature. Features were tracked using the ticketing system. This implies relying on people to update the information as there is no automated audit trail any more.

When I suggested a Deployment Pipeline, I received some backfires.

“I can see this working for teams of three, but this cannot work for ten-engineer teams. Team members will be blocked by other team members, preventing them from delivering.” Of course, if we have a team of individuals each working in isolation on their allocated feature, this makes things harder. But that is not a team. It is merely a bunch of individuals assigned to a software product where everyone is incentivised to deliver what they are working on. This is not a team focused on delivering outcomes. This is a team focused on output.

The embedded HP LaserJet FutureSmart Firmware shows this easily scales to 400-person distributed across three continents, integrating 100-150 changes per day into Mainline and producing every day 10-15 good builds of the firmware. If this works for embedded software with 400 engineers, this might work for a ten-engineer team. Without even mentioning Google.

The team raised a common concern about unfinished functionality. Let us say three features are being implemented at the same time: features A, B and C. All three features are in the QA environment but the client only gave a go for feature A. Or feature A is ready, but testing reveals issues for features B and C. Does that mean we have to revert features B and C? No! Features B and C can go into production together with feature A. We simply do not release them. There is a difference between deploying and releasing. Deploying means deploying code into production. Releasing means making a feature available to users. Deploying and releasing should be decoupled. That is when Feature Toggles come into place. Feature B and C get into production but are hidden from the user. However, Feature Toggles come with a decent amount of practices to adopt to avoid nasty outcomes. But, this is still a more straightforward approach than environment branches.

What if we need to apply an urgent hotfix? If we have to go through all environments that will slow us down. As already mentioned, one of the Continuous Delivery corner stores is to keep the build and test process short to accelerate feedback and to deliver quickly. Fixes should always follow the same delivery process as features to avoid the Dual Value Stream antipattern. That said, Having a Fast Build is hard work.

The failing End2End Tests was another matter. As the name implies, the tests covered several services not necessarily managed by the team. As a result, the tests often failed for reasons outside the team’s control. This is reasonably frustrating. Therefore, the team wanted to have the flexibility to still deliver in production despite failing End2End Tests. Especially, as the teams were under management pressure to deliver. The team’s request is therefore comprehensible. End2end Tests are an antipattern. Continuous Delivery advocates Automated Acceptance Tests together with Contract Tests to cover the integration between services. Both are in control of the team and will fail for reasons induced by the team. The team is again empowered.

The team realised that the fact they could bypass environments was problematic. Hence, they suggested that the delivery system checks whether every commit went through all environment branches. That is a manifestly bad idea. By all means, avoid fixing a complex system by adding another layer of complexity. Organisations need simple delivery processes like the Deployment Pipeline.

… most troubles and most possibilities for improvement add up to proportions something like:

- 94% belong to the system (responsibility of management)

- 6% special

– W. Edwards Deming, Out of the Crisis, p270

Many times, quality problems are caused by the system. In this case, the use of environment branches. It is then distressing to see leadership pressurising teams to deliver while still expecting quality. When teams are under tension, they will cut corners. Leadership is responsible for the system teams are working in. It is up to leadership to allow teams to improve. Undoubtedly, they will naturally evolve towards a Deployment Pipeline with all the benefits that come with it.

Acknowledgements

Martin Dürrmeier to review the article and provide essential insights.

References

-

Organisation antipattern: Release Feature Branching, Steve Smith

-

Continuous Delivery, Dave Farley and Jez Humble