Everyone in the IT industry agrees, and research confirms this, that Continuous Integration is a required practice to realise quality and stability. Yet, few teams have truly implemented Continuous Integration. Based on the limited data I have, it appears only one in ten teams genuinely practices Continuous Integration. This is surely not a hard number, but I think it is already on the high side. Why is that?

Update Jul 27th, 2025: Clarify the context of OSS and regulation.

First, there is a massive Semantic Diffusion around Continuous Integration. It got worse over the past two decades. Mainly with the advent of GitHub with Pull Requests and GitLab with Merge Requests. Teams like to redefine Continuous Integration by telling: “We have our GitLab-CI running against all of our branches, you know!”. This is a reductionist view on Continuous Integration as merely a tooling problem. However, Continuous Integration is a team practice that, on its own, requires another series of practices to be adopted to realise it. In reality, we do not even need a central build to implement Continuous Integration. We only need two tools.

Having an automated build running against all the branches is, in actuality, a good thing. But it is not Continuous Integration. We are not integrating at all. By rebasing mainline onto the branch, we only perform a Semi-Integration. But we have no information whatsoever on whether the branch integrates with all the parallel branches. At this point, CI stands for Continuous Isolation. The rest of the team ignores how their work will be impacted by our branch.

Because of this semantic diffusion, around 2006, people from ThoughtWorks started to speak about Trunk-based Development to mean true Continuous Integration with a single long running branch, Mainline, and no other branches of any kind as opposed to the common implementation of “Continuous Integration” using a central build server with branches, mostly particularly long-lived. Here is the thing: Continuous Integration implies trunk-based development with straight commits to mainline. Yet according to Accelerate (p55), fewer than three active parallel branches with a lifespan of a maximum 24 hours equate trunk-based development. I understand that the data shows where the performance hits the cliff edge. However, the research outcome was not helpful. It appears to have fed the semantic diffusion more. Nowadays, many teams pretend to practice trunk-based development or even “scaled” trunk-based development, but forget that their branches last for days or more.

Then we have the commandment “You shall not commit straight to mainline”. Is this the first IT-axiom? Or a spiritual law? From where does this come? Specially, given that when RCS was introduced in 1982 as one of the first version control systems, everyone stuck to the mainline, though it had support for branches. Everyone was cautious. This approach remained until the introduction of Git in 2005.

Provided that Continuous Integration means single-branch development, teams fear breaking things, the build or a running service. Therefore, they tend to adopt feature branches and Pull Requests to create a false sense of safety and control. To not break things, it requires adopting a shear amount of engineering practices. Here is the problem. Teams lack the necessary engineering skills to make this work. Particularly, they lack incremental software engineering skills. It takes effort to split work into a sequence of small incremental changes that keep the system always working and in a releasable state. That is hard work. We have to think harder, and we will move a bit slower. But, with the advantage of having always working software. This enables on-demand production deployments at any time. This is a considerable competitive advantage.

This fear of breaking things is particularly oriented towards breaking the build. Agreed, one of the Continuous Integration practices is to Agree as a Team to Never Break the Build. Indeed, this puts some pressure on teams. Still, the build will, regardless, break from time to time. That is fine. As my friend, Yves Hanoulle, says: “When a team only has green builds, the team has a problem”. That means the team becomes stagnant. More important is the time to recover. Hence, the team has to Fix a Broken Build Within 10 Minutes. Yet another practice many teams lack. They spent too much time trying to fix the build under pressure instead of just reverting the last failing commit. That is mostly due to a widespread Sunk-Cost Fallacy. But, to quickly fix a broken build, this calls for Having a Fast Build.

The lack of automated tests emphasises this fear even more. We would think that automated tests are nowadays the norm. Hell no. Manual testing or the absence of a comprehensive automated test suite is still common. Naturally, teams fall back to Pull Requests as a safety net. As if the Pull Request code review will prevent something from breaking. Needless to say, this will not happen. Even with a decent set of automated tests, systems will breach, anyway. Thus, with no automated tests, even more things will be disrupted. To implement Continuous Integration successfully, we need to Have a Vast Amount of High-Quality Automated Tests.

To integrate at least once a day, we need to commit at least once a day to mainline. To achieve the benefits of Continuous Integration, we should integrate multiple times per day, hourly or even multiple times per hour. That means committing multiple times per hour to mainline. Because of the requirement to Run a Local Build together with Commit Only on Green, we have to Have a Fast Build. Though here is the trouble. Most teams have especially slow builds. Or do not have staged builds where the fast narrow-scoped tests are executed first, followed by the slower broader-scoped tests. If a build takes 45 minutes to complete, that means we can only commit every 45 minutes. If we want to integrate continually, we need to keep the build under ten minutes, preferably five. This is tough work and necessitates continuous improvement. Do teams have this habit?

Other than that, there is, among teams, a certain unawareness of what high performance looks like. Few engineers have experienced that. Even if engineers who have experienced high-performance enter the team, the team sticks to what they know, following unconscious bias. Oftentimes causing teams not to see the problem, leading to a team’s Dunning-Kruger effect of overestimating themselves as being high-performing, where effectively they are nowhere. Likely because of a misconception of seniority as having years of work experience rather than having experienced many organisations. We might conclude teams lack seniority.

Lastly, a lack of seniority indicates an absence of economic sense. As one leader once said: “One can only be senior if they understand the economic consequences of their technical choices.”. Continuous Integration is what it is for economical reasons. It increases quality and stability, accelerating speed and shortening times to market, which reduces the cost of delay. This is money! This is about increasing turnover.

Conclusion

In conclusion, teams do not practice Continuous Integration because:

- There is Semantic Diffusion on the meaning of Continuous Integration, leading to implementations using branches and central builds.

- Teams fear breaking something.

- Because of a lack of engineering skills.

- And a lack of automated tests.

- Slow builds refrain from integrating regularly.

- Lastly, unawareness of economic reasons to implement Continuous Integration.

To clarify, Continuous Integration, as intended in this article, is compatible with regulation and compliance. No single reason should prevent practicing Continuous Integration in a regulated environment. To the contrary, it will significantly help in satisfying compliance requirements. But, sure, as a team, it requires to change some habits and be curious to succeed.

However, it is true that Pull Requests with status-checks are a good fit for OSS when core maintainers want to accept contributions from the outside world. This is a classic low-trust environment. Yet, the core maintainers should practice Continuous Integration when contributing themselves. They should operate under high-trust.

In conclusion, even though teams like to see themselves as experienced and high-performing, without true Continuous Integration, they will be none.

Acknowledgements

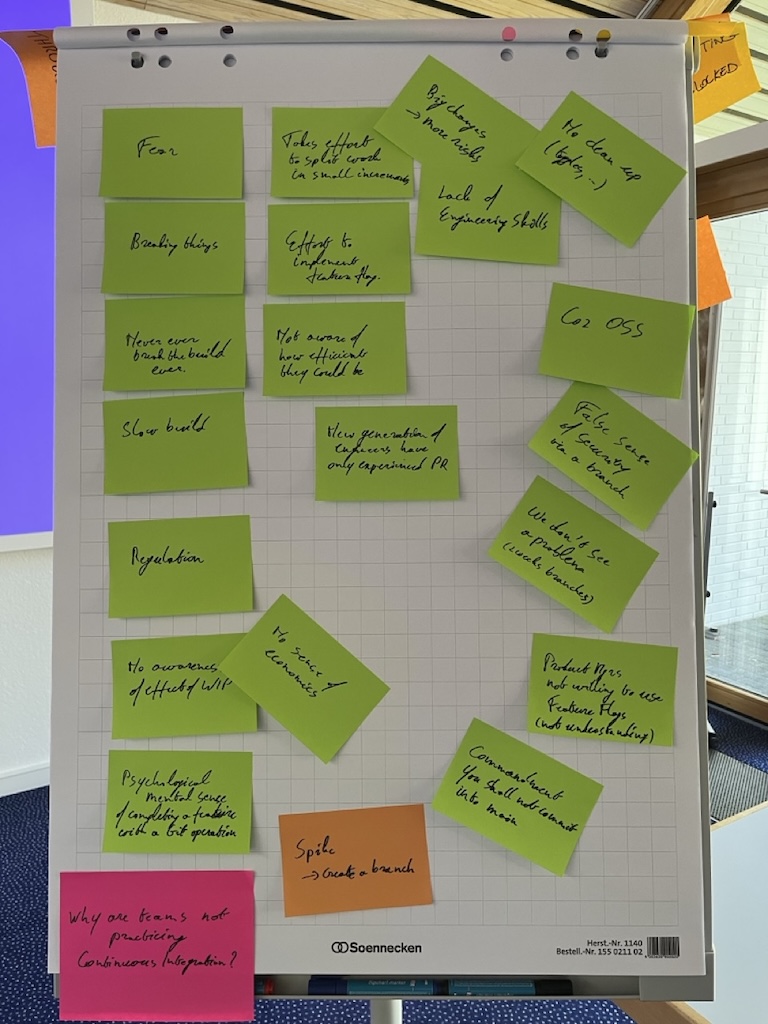

The participants in my SoCraTes 2025 open-space session “Why are Teams not practising Continuous Integration?” for their valuable input.

Martin Mortensen for his feedback.

Steve Fenton for highlighting the research data showed the performance limits of branches.

Related articles

Definitions

Mainline

The Mainline is the line of development in Version Control, which is the reference from which system builds are created that feed into a deployment pipeline.

For CVS and SubVersion, this is trunk. For Git, this is the remote main branch. For Mercurial, this is the remote default branch.