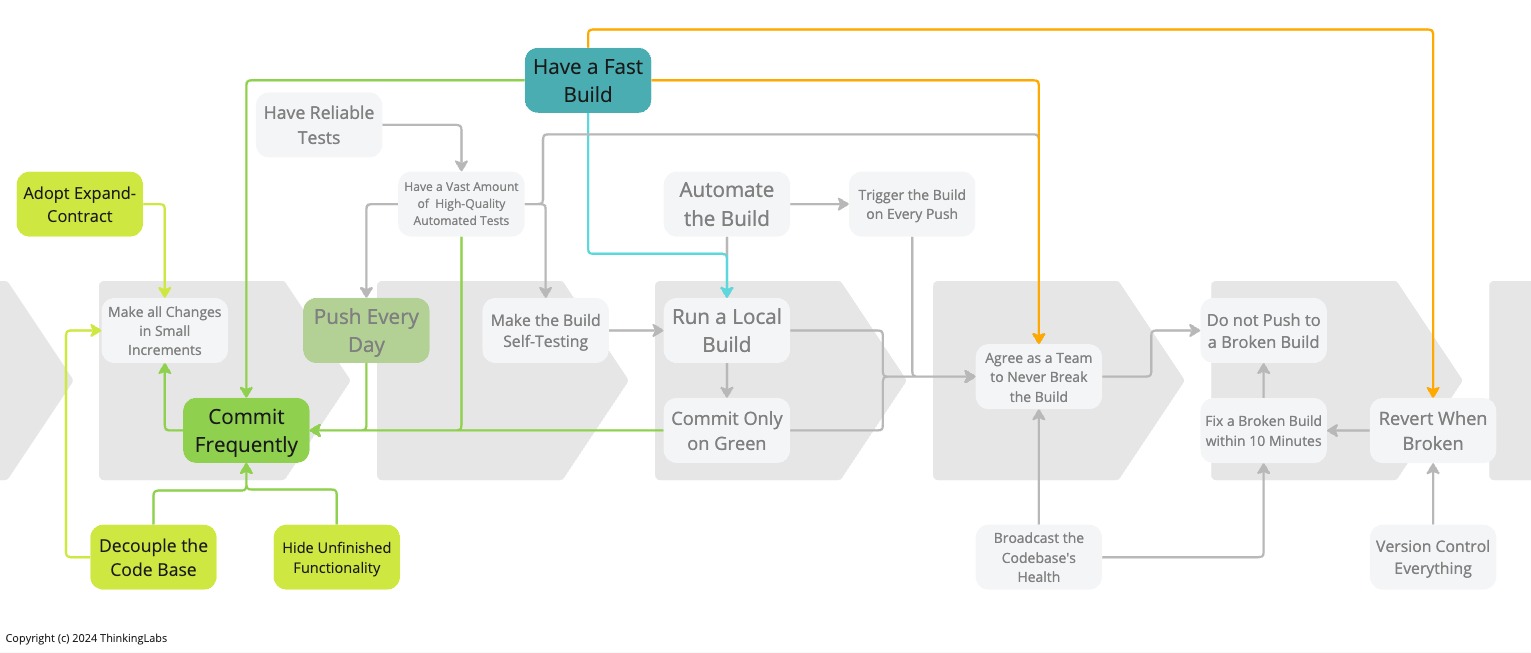

So we implemented Continuous Integration. It gives us the confidence to deliver – great! Though, we feel we are stuck in a suboptimal situation. We have not yet gained all the benefits that should come with Continuous Integration. We cannot deliver fast enough without causing stress on the team. How can we get the most out of it while keeping the team untroubled? Which additional practices are we missing? Which ones should we acquire? How can we raise the bar?

Update Dec 17, 2024: Reference TDD as an enabler for Commit Frequently.

Update Dec 18, 2024: Reference the Unix philosophy and the Dependency Inversion principle as an enabler of Decouple the Codebase.

Update Dec 18, 2024: Include the Expand-Contract infographic.

Update Dec 21, 2024: Include some questions from Agile Testing Days 2024.

Update Jan 24, 2025: Add the HP LaserJet FutureSmart case as a scaling example.

Push Every Day is one of the six foundational practices to get started with Continuous Integration. No matter how, if we want to leverage the benefits of Continuous Integration to the fullest, integrating once per day will not make it. That is pertinent but inadequate. To raise the bar to the next level, we have to Commit Frequently. After all, the central premise of Continuous Integration is integrating early and often on Mainline. It enables speed of delivery. As a result, it accelerates feedback, amplifies quality, and allows us to recover quicker from production instabilities.

People regularly indicate that this focus on delivery speed puts pressure on teams. I can see that. But we are missing the point. We want teams to be serene and comfortable, without stress and fear. Exactly that empowers the team to deliver at speed. However, to enable this, it requires adopting Decouple the Codebase, Hide Unfinished Functionality and Expand-Contract.

To satisfy Commit Frequently, we have to commit at least once per hour, preferably multiple times per hour. It contributes to the real-time communication of changes with the rest of the team. This is especially important when refactoring. Thoughtful engineers will commit and push after every little refactor. This avoids surprises for the rest of the team when one team member releases a series of refactorings in one big batch that results in a significant redesign. We want to avoid that. We should communicate early and often to allow the rest of the team to adapt to our changes.

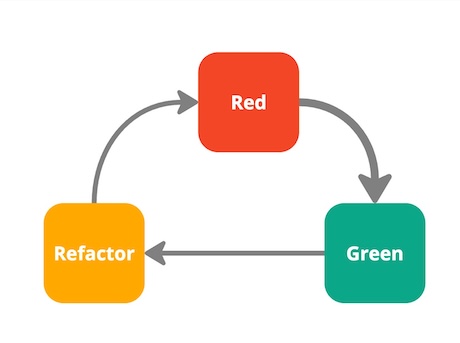

This is when Test Driven Development (TDD) comes in. We write a small failing test. We add just enough production code to get the test passing to green. When the tests are green, we commit and push into Mainline. Then we refactor. If the test fails, we revert. When the test is back to green, we commit and push again into Mainline.

Test Driven Development creates this commit cadence to enable Commit Frequently and is required to attain a state of Continuous Integration.

When we Commit Frequently we reduce the size of our changes. Merge conflicts are unlikely and broken builds are infrequent.

It also reduces risks. If the build happens to break, it is fairly easy to find the root cause because the changeset is so small. Probably also, because we only introduced the failing change just minutes ago. We still have enough context to fix the build readily. Getting the build back to green within ten minutes becomes attainable.

If we have to revert a failing commit, that too, will be effortless. Because the change is so small, we are not plagued by the sunk cost fallacy. Deciding to revert becomes straightforward.

Once we commit and push every so often into the remote Mainline, multiple times per hour, it becomes apparent that version control branches, and specifically Feature Branches with Pull Requests, turns out to be untenable. The cognitive overhead is way out of balance compared to the illusive benefits. Additionally, Pull Requests will bring to a blatant halt all the benefits we built up with the practices that bring Continuous Integration.

Inherently, Commit Frequently creates a gentle design pressure to work in many more smaller steps, to keep the code base even more decoupled, to further speed up the build, and lastly to increasingly hide unfinished functionality. This creates a virtuous circle resulting in committing all the more frequently.

To Make all Changes in Small Increments it is vital to Decouple the Codebase. When a codebase is too coupled, it becomes tough to adopt incremental software engineering skills. Any change will rip apart the application and prevent the application from working all the time. We find ourselves not releasing anymore at any time, incurring delays in delivery and an increased opportunity cost.

Adopting Ports and Adapters together with the four rules of Simple Design, intentional code duplication (with Expand-Contract), the Unix philosophy and Dependency Inversion Principle helps to decouple the codebase. Interestingly, these patterns not only amplify quality and improve maintainability, they also optimise the required engineering time for new functionality. It proves to be cheaper to introduce changes.

Inherently, when a code base is decoupled, we can Commit More Frequently.

Most often, a feature takes a fair amount of time to implement. It involves a series of commits. We grow the feature small step by small step, commit by commit. How can we ensure the unfinished functionality is not released to the end user?

The classic approach is to use Feature Branches. As long as the feature is not done, the branch is not merged into Mainline. Intrinsically, the feature is hidden using the version control system as a manual toggling mechanism. This has a downside. The feature is not integrated with all the other ongoing changes while the feature is being implemented. We are blind to whether the feature will cause any integration problems until the feature is finished and merged into Mainline. This delays feedback. Inevitably, it negatively impacts quality and necessarily increases the lead time to market.

Remember, the central premise of Continuous Integration is to integrate early and often to get feedback within minutes.

Instead, we could plainly Hide Unfinished Functionality. This is likely the most uncomplicated practice to adopt. It is downright acceptable to have unfinished functionality sitting in production provided it is not discoverable and does not introduce any security risks. Commonly, we do not need elaborate Feature Toggles for that. For instance, when adding a new screen to an existing user interface we simply do not wire the screen into the navigation. We only do that at the end, once the screen is ready. The same is true for new API endpoints or backend services. As long as they are not ready, we do not document them or we do not use the backend service.

Sometimes, we have to modify a widget from an existing screen or the behaviour of an existing backend service. In that case, Feature Toggles will be necessary. However, if we do not want to self-sabotage ourselves, this requires managing toggles. We have to be mindful and conscious about that. If we do not, it can go terribly wrong. We are aware of one organisation that went bankrupt because of unmanaged toggles.

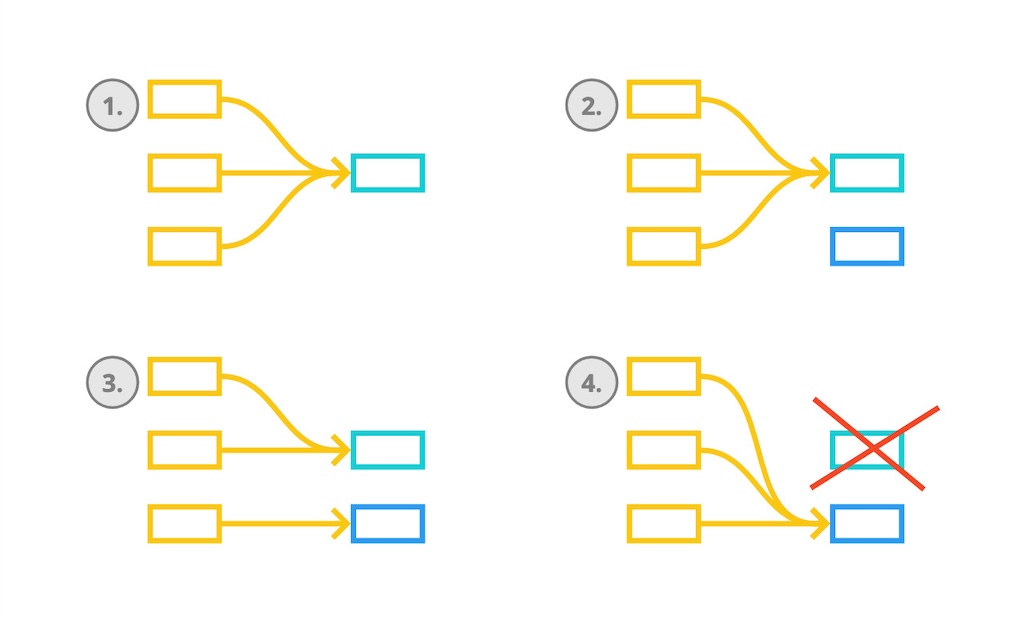

In some cases, we will have to perform a large refactoring that can rip apart the application for an extended period. Let us say, we want to replace a library or a framework with another or we need to break backwards compatibility on a certain service. Here too, the classic approach is to use Feature Branches. Again, the problem is we are not integrating. In the meantime, while the large refactoring is happening, new functionality is added. When the refactoring is finally ready, the integration will be tedious and time-consuming. Accordingly, delivery comes to a halt and delivery lead times go through the roof. On top of that, we have created a massive amount of inventory that we do not dare to integrate as we fear how complicated that will be.

How can we do this more smoothly, in a more effective way, without impacting the flow of delivery? Adopt Expand-Contract. This is the intentional code duplication we mentioned earlier. Once we understand Expand-Contract, it is gold!

Truthfully, Expand-Contract will introduce a certain level of complexity. We will have to think harder. We might move slower. But, it brings the tremendous advantage of delivering new functionality while a large-scale refactoring is happening that takes days, weeks or even months to complete. The application keeps working at all times, allowing us to perform on-demand releases anytime. At no single moment, we are blocked. The flow of delivery steadily continues.

Yet, Expand-Contract is critical in avoiding breaking changes that impact the team. It necessitates Commit Frequently to keep communicating changes with the team. That will especially help, but that is still insufficient. Verbal communication is indispensable. “We intend to perform this change. We expect that might have this and that impact or not.”

To Commit Frequently into Mainline, we must Run the Local Build repeatedly before each commit to satisfy Agree as a Team to Never Break the Build. Additionally, when engineers commit multiple times per hour, they execute the Local Build multiple times per hour. That means we ought to Have a Fast Build. This is primordial! But also hard work. Lots of teams struggle with that. Often teams hide slow builds behind version control branches and remote Pull Request builds that in line introduce a decent amount of context switching and fatigue.

When the build is too slow, two things can happen. Either teams do not tend to run the Local Build before committing. We then run the risk of introducing regressions, thus impacting delivery throughput. Or teams tend to execute the build less often. In that case, batch work is introduced. We know from Lean Manufacturing that it drives down quality and consequently inflates time to market.

But, what is fast? We focus on a Local Build (and thus also a Commit Build) of five minutes but no longer than ten minutes. If we can bring it to 30 seconds, it will avoid any hallway sword-fighting sessions.

We could argue that Have a Fast Build contradicts with Have a Vast Amount of High-Quality Automated Tests. When adding more tests over time, the build typically expands in execution time. How can we keep the build fast? First, we should consider including a fitness function as part of the build to monitor the build lead team. Whenever it exceeds five minutes, it fails the build. At that point, we need to inspect individual unit test execution times. Any unit test that takes one second to execute is a red flag and requires immediate attention. Second, at some point, we cannot run all tests inside the Local Build (and the Commit Build) anymore. Now, we have to evolve the build towards Progressive Testing. We split test execution into several stages. The fast unit tests execute during the first stage, the Commit Build. The slower, broader automated tests are delayed to later stages. Lastly, later on, we might need to optimise more by adopting parallelising test execution and looking at the software system performance. Also, we should consider deleting obsolete tests that have no value anymore.

With all this automation in place, we may well think there is no room for manual actions. The opposite is true. All this test automation ensures regressions are covered, removing the need for time-consuming manual regression tests. Ultimately, it gives the team time and space for valuable Exploratory Testing that can uncover potentially serious system-level bugs or usages we have not pondered.

To conclude, if we want to raise the bar, it is fundamental to Have a Fast Build. This is crucial as it allows us to commit all the more frequently, enabling us to work in increasingly smaller steps. But to Commit Frequently, also requires to Have a Decoupled Code Base and understanding we have to Hide Unfinished Functionality. Lastly, Adopt Expand-Contract helps us to refactor in small increments and to commit frequently when refactoring and delivering new functionality at the same time.

Can this scale? Absolutely! We saw an organisation of 150 engineers distributed over 15 teams working on a single monolith. All teams commit to a single repository, triggering a single build and releasing every fortnight. The embedded HP LaserJet FutureSmart Firmware scaled to 400-person distributed across three continents, integrating 100-150 changes per day into Mainline and producing every day 10-15 good builds of the firmware. Google being the ultimate example that this can scale. In 2016, Google had 25.000 engineers working from a single Mainline with 16.000 changes per day. Continuous Integration is the only process known to scale effectively without the nasty and unpredictable integration, stabilisation and hardening phases associated with other approaches like release trains or feature branches.

Looking at some of the practices, one might think this presupposes a mature team. Sure, maturity helps. But, do not be fooled. Do not assume that a mature team will naturally flourish and conversely, that this cannot possibly work for a novice team. We have had outstanding experiences with novice teams and have seen first-hand accomplished teams with skilled engineers unable to pull this off. To progress, we must have a growth mindset and openness to novelty. Then miracles happen …

Showing my age: Before we had version control, we only did trunk-based development. Even with several people. I was certainly a novice then. It worked. (We talked to each other when things didn’t work.)

– Johanna Rothman (@johannarothman, Jul 15, 2021

Related Articles

- Continuous Integration! Where to Start?

- The Practices that Make Continuous Integration

- On the Evilness of Feature Branching - A Tale of Two Teams

References

Definitions

Mainline

The Mainline is the line of development in Version Control which is the reference from which system builds are created that feed into a deployment pipeline.

For CVS and SubVersion, this is trunk. For Git, this is the remote main branch. For Mercurial, this is the remote default branch.

Commit Build

The Commit Build is a build performed during the first stage of the Deployment Pipeline or the central build server. It involves checking out the latest sources from Mainline and at minimum compiling the sources, running a set of Commit Tests, and building a binary artefact for deployment.

Commit Tests

The Commit Tests comprise all of the Unit Tests along with a small simple smoke test suite executed during the Commit Build. This smoke test suite includes a few simple Integration and Acceptance Tests deemed important enough to get early feedback.