When tests occasionally fail because they are flaky, we can not rely on the tests any more to identify a good release candidate. At that point, we lose the codebase health monitoring. The benefits of Continuous Integration fall flat. On-demand production releases are jeopardised.

The objective of Continuous Integration, and by extension Continuous Delivery, is to eliminate bad quality release candidates as early as possible. Only changes that successfully moved through all stages of the deployment pipeline, and that have been thoroughly tested, get into production.

Decidedly, to discard unfit release candidates for production, we must have a reliable, deterministic, consistent, and repeatable Build. This is paramount!

reliable: consistently good in quality or performance; able to be trusted

– Oxford Languages

When tests are not reliable, we cannot trust them.

deterministic: of or relating to a process or model in which the output is determined solely by the input and initial conditions, thereby always returning the same results.

– Dictionary.com

When tests are not deterministic, we will obtain wildly varying results when continually executing them. Once more, we cannot trust the tests.

consistent: always acting or behaving in the same way.

– Britannica

When tests are inconsistent, they will not behave the same way when executed many more times. Again, we cannot trust the tests.

repeatable: something can be done again.

– Cambridge Dictionary

When executing tests repeatedly, we want them to be deterministic and consistent. The result should always be the same. When running tests 1000 times without any code changes, they should be green 1000 times. Not once red, and 999 times green. If they fail once in 10.000 runs without code changes, they are unreliable. Once again, we cannot trust the tests!

Even if we Have a Vast Amount of High-Quality Automated Tests, as soon as we cannot trust the tests, they have little value. Our vast amount of automated tests become useless. Right now, we will not mind any failing tests. After all, re-executing the tests might pass them to green. On that occasion, we can still perform an on-demand production release anyway. Nothing is blocking us. We only live once, don’t we?

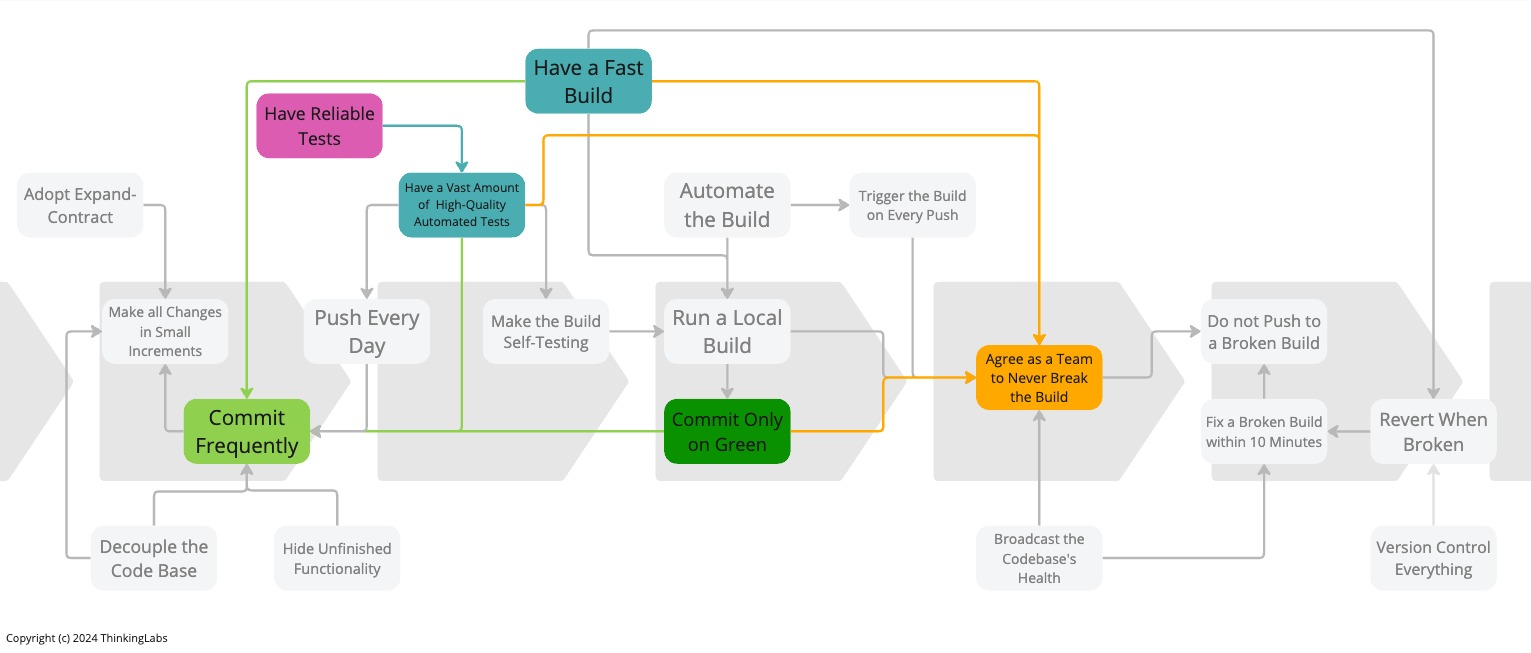

This conveys that unreliable tests disable Have a Vast Amount of High-Quality Automated Tests. Thus, it removes our ability to satisfy Agree as a Team to Never Break the Build, the most crucial practice to adopt to implement Continuous Integration successfully.

But there is more. Once we have one flaky test, we are at the start of much more flakiness. We will soon have two, three, five and more unreliable tests. It now becomes damn hard to satisfy Agree as a Team to Never Break the Build. Because the build now became non-deterministic, we will, time and time again, never know upfront whether the build will be green.

Because we have no faith in the automated tests, we lose confidence in the release process. If tests are green, are they truly passing? When they are red, are they indeed failing? In theory, our build is broken. When the build is broken we do not have Continuous Integration.

Without Continuous Integration, our software is broken until someone else proves it works.

Hence, we find ourselves adding another layer of expensive, time-consuming manual regression testing as an additional quality gate to gain assurance that our release candidate is genuinely good.

Be aware, this is not to say that manual testing is a bad thing. We do need Exploratory Testing, preferably in production, on top of automated tests to find all the unknowns. The automated tests can only check the knowns. Despite that, manual regression testing as a process gate is a bad idea. Research indicates that process gates drive down quality and introduce delays.

Ultimately, we find ourselves with a quality gate hoping to increase our confidence, but with a significant chance to obtain lower quality. Additionally, time to market is delayed and we incur an opportunity cost. Not particularly an economically healthy situation.

We might as well delete the unreliable automated tests. The outcome will be the same. In both cases, we still need manual regression tests to instil a quality illusion.

Even though this sounds attractive, do not delete unreliable tests. After all, they do not provide any assurance. But they do give information and somehow valuable feedback. Yet, this requires a more in-depth analysis. It will take time to figure out what is happening. Again, we pay a lead time tax.

But, once we have flaky tests, how do we get out of this? How do we solve this? How do we get to a better, more manageable situation empowering us to perform on-demand production releases at any time?

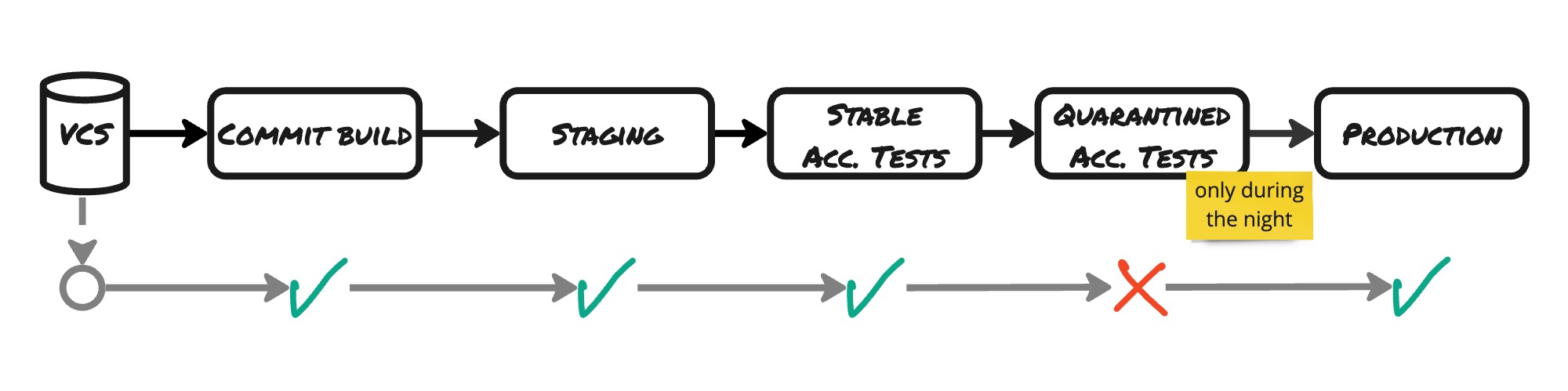

To build our self-assurance, we should place the unreliable tests in quarantine. We split the automated tests into two sets of tests:

- A set of stable tests. They are executed all the time. If any of these fail, they drop the release candidate.

- A set of unstable, quarantined tests. These are only executed overnight. If they fail, it never blocks a release. But it still provides us with precious information.

Note that this is only a solution to a symptom, not being able to count anymore on our automated tests to make a release decision. This is now again possible. We now need to tackle the root cause. We must bring the number of flaky tests back to zero by gradually fixing them. Turning them again into reliable tests. This is hard work!

As with many practices that make Continuous Integration, if we want to keep our organisation financially healthy, our tests must be reliable, deterministic, consistent, and repeatable. If they are not, we must quarantine unreliable tests and progressively fix them.

Acknowledgments

Maaret Pyhäjärvi for bringing this practice to my attention after attending my talk The Practices that make Continuous Integration at ScanAgile23.

The Series

The Practices That Make Continuous Integration series:

- Team working for Continuous Integration

- Coding for Continuous Integration

- Building for Continuous Integration

- Make the Build Self-Testing

- Push Every Day

- Trigger the Build on Every Push

- Fix a Broken Build within 10 Minutes

- Have Reliable Tests

- Broadcast the Codebase’s Health

Definitions

Mainline

The Mainline is the line of development in Version Control which is the reference from which system builds are created that feed into a deployment pipeline.

For CVS and SubVersion, this is trunk. For Git, this is the remote main branch. For Mercurial, this is the remote default branch.

Build

In this case, the build is seen as a general activity encompassing several stages from a Deployment Pipeline, often also called a Staged Build. It involves the Commit Build as well as the execution of an eventual full set of Automated Acceptance Tests.

Commit Build

The Commit Build is a build performed during the first stage of the Deployment Pipeline or the central build server. It involves checking out the latest sources from Mainline and at minimum compiling the sources, running a set of Commit Tests, and building a binary artefact for deployment.

Commit Tests

The Commit Tests comprise all of the Unit Tests along with a small simple smoke test suite executed during the Commit Build. This smoke test suite includes a few simple Integration and Acceptance Tests deemed important enough to get early feedback.