In part 2 of this series - Why do Teams use Feature Branches? - and part 3 - But Compliance!? I went into all the possible reasons teams mention themselves to why they use feature branches. This time I want to go deeper into the problems introduced by the use of feature branches.

Before we move on, let me first clarify two definitions.

- What is mainline?

- What is Continuous Integration?

Mainline is the line of development which is the reference from which the builds of your system are created that feed into your deployment pipeline.

– Jez Humble, On DVCS, Continuous Integration and Feature Branches

Continuous Integration is a software development practice where members of a team integrate their work frequently - usually, each person integrates at least daily - leading to multiple integrations per day. Each integration is verified by an automated build […].

– Martin Fowler, Continuous Integration

Or said differently …

[It] is a practice designed to ensure that your software is always working, and that you get comprehensive feedback in a few minutes as to whether any given change to your system has broken it.

– Jez Humble, On DVCS, Continuous Integration and Feature Branches

This involves:

- Everyone in the team commits to mainline at least once a day.

- Every commit triggers an automated build and execution of all the automated tests.

- If the build fails it is back to green within 10 minutes.

The easiest way to fix a broken build is to revert the last commit that brings us back to the last known good state.

Note that Continuous Integration is a practice on its own! It requires few particular tooling.

The only tools we need for Continuous Integration are :

- a version control system,

- an automated build,

and team commitment to never break the build.

Extreme Programming defined Continuous Integration this way in the late 1990s. The idea was to have only one branch for the whole team, i.e. mainline. Whenever code could not integrate they wanted to receive alerts as soon as possible. Humans could perform the practice. No servers or daemons were required.

Still, nowadays, many teams choose to work with feature branches for the various reasons mentioned in part 2 - Why do Teams use Feature Branches? - and part 3 - But Compliance!?. But this comes with a myriad of problems.

The Problems

It delays feedback

Remember, Continuous Integration is a practice to ensure always working software on mainline and to get feedback within minutes whether a change broke the application or not.

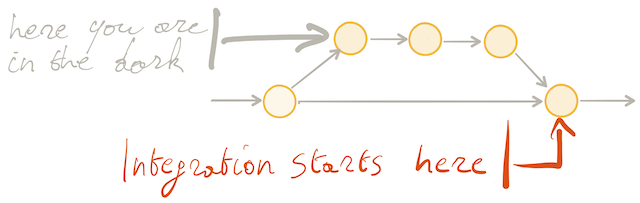

With feature branching this feedback is delayed. As long as we have not merged our branch back to mainline, we simply do not know if our changes broke the application or not. Continuous Integration is only triggered the minute we are merging back to mainline. Only then starts the integration of what is on the branch into the codebase.

This delay in feedback increases with the duration of the branch and with the number of parallel branches.

If the branch lives for a couple of hours, feedback is delayed by a couple of hours. If the branch lives for a couple of days, feedback is delayed by a couple of days.

Often the solution to delayed feedback is to start even more work, instead of finishing the work that is already in progress. Or, worse, throw even more people to the problem to then hit Brooks’s Law. Hence, again increasing the work in progress together with the number of parallel branches. To result with waiting times going through the roof and delaying feedback even more. All of this, of course, to optimise for utilisation. And here we are in hell.

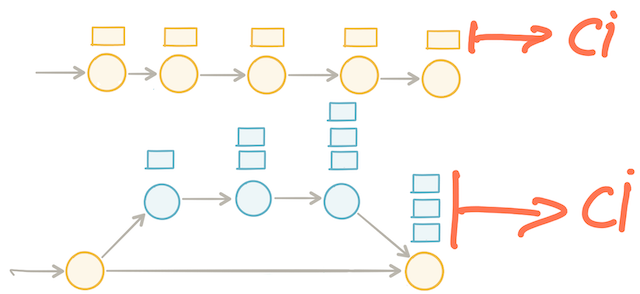

Or teams like to redefine Continuous Integration by saying: “We have our [preferred centralised build tool] running against all of our branches”.

Having an automated build running against all of our branches is certainly a good thing. But it is not Continuous Integration. We are not integrating. The only feedback we get is whether the code that exists inside our isolated branch still compiles and whether we have not introduced any regressions against the tests that exist inside that isolated branch. We do not get any feedback whatsoever on whether our changes integrate well with the changes that exist on all the other existing parallel branches. Even when all tests pass on the branch, they still may fail when merging back into mainline. The real authoritative feedback only happens at merge time when integrating, once the feature is finished. Everything else is a guess.

So, from this moment on CI stands for Continuous Isolation and not any more for Continuous Integration. We are not integrating outside changes and the rest of the team does not know how our changes integrate with their work.

The value of accelerating feedback resides in failing fast. Problems are spotted early, within minutes. We achieve this when committing frequently, multiple times a day, regardless of code complexity or team size. But it requires we work very hard to keep getting fast feedback. This means if the build is too slow, we need to speed up the build; if tests are too slow, we need to write better and more concise tests; if the hardware is too slow, we need to buy faster hardware; if the codebase is too coupled, preventing us to write concise tests, we need to decouple the codebase.

It hinders the integration of features

If we are implementing multiple features at the same time in parallel, integrating these features becomes exponentially harder with the number of features that are being implemented in parallel, and the number of changes required to implement these features.

One way to avoid these integration problems is using what Martin Fowler calls Promiscuous Integration. Be aware, Martin does not advise the use of Promiscuous Integration. He just named the pattern.

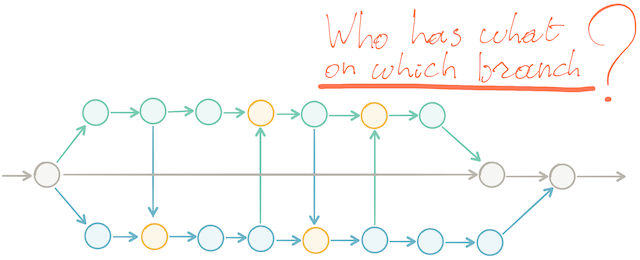

To use changes from another feature that is currently being implemented, we cherry-pick some commits from that feature branch into our branch. Now, we are in fact communicating changes between branches.

However, the biggest concern I have against Promiscuous Integration, apart from introducing a lot of process complexity, is that with all that cherry-picking, we lose track of who has what on which branch. Also for test engineers, it becomes a painful exercise to figure out where the risk resides, on which branch and what to focus feedback on. This creates cognitive load that unmistakably harms IT delivery throughput and time to market for new features.

Compare this complexity with the simplicity of having everyone in the team commit its changes immediately to mainline. They communicate their changes straight away with the rest of the team. Helping to create a shared understanding of the codebase and a collective ownership of the codebase. Inevitably, this leads to better quality and higher IT delivery throughput and reduces the lead time and the time to market.

It hides work for the rest of the team and therefore disables communication

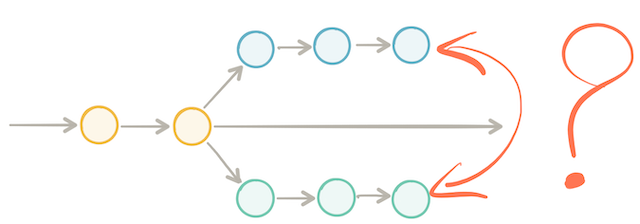

As long as we have not yet merged our branch back to mainline, the rest of the team simply does not know in which direction we are taking the code to implement the feature we are working on.

This is fine as long as everyone on the team works on different parts of the application. But, the minute two team members are working on the same codebase area they are each blind to how their work affects the other person. As a result, collaboration is sacrificed because everyone is focused on the changes happening on their isolated branch.

On the other hand, if we are committing more frequently to mainline, we communicate to the rest of the team the direction we are taking with the code to implement this feature. For example, we could add a conditional indicating the start of the new code we are working on and have it disabled by default. From then on the rest of the team sees the newly introduced changes. They can immediately spot how this affects their work and thus can instantly adapt to these changes. Naturally, collaboration and communication starts inside the team. Therefore, it eliminates the classic rework happening at merge time and enables the fast flow of work through the value stream.

To summarise: Working on mainline forces communication!

It discourages refactoring

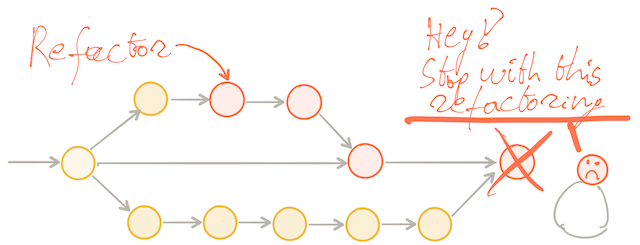

Because feature branches hide work for the rest of the team, it also discourages the adoption of refactoring.

When we are just adding new code, integrating that code is fairly straightforward. But if we are refactoring our code, we are introducing new abstractions and new concepts. For instance, we rename a method; extract code as a new method or a new class; reorder methods inside a class; or move code between classes.

Unfortunately, Version Control Systems are not aware of semantic changes which make merging arduous. Either this introduces tons of conflicts at merge time or even worse Semantic Bugs.

If we have two team members, each working in parallel on their feature branch.

One team member refactors and merges back first. The other person has a significant amount of changes on their branch. Merging back to mainline will be far more painful for that second person. Probably, that will create some tension inside the team. Even in teams that work downright well together, where they understand this can happen and so do not necessarily get upset, still one has to “give in” and compromise. Which is never a good feeling.

The longer the branch lives and the more refactoring has occurred, the harder it becomes to merge back because of all the potential merge conflicts and all the potential rework that might be required at merge time. Merging back becomes a time-consuming and very unpredictable activity. Inevitably this slows down the team.

It is exactly this slow down of the team that discourages the adoption of refactoring inside the team. We all know, that not enough refactoring prevents paying back technical debt. When not paying back technical debt, adding new functionality to the codebase becomes considerably more tedious and complicated. Again, this slows down the team. To then end in this vicious circle where the team slows down over time. Eventually, they come to a halt and nobody truly understanding why and how this happened.

It works against Collective Ownership

Collective Owernership is one of the key practices from Extreme Programming: anyone who sees an opportunity to add value to any portion of the code is required to do so at any time.

This instigates the following benefits:

- Complex code does not live very long, because someone else will soon simplify it. For that reason, adding new functionality will never be laborious, or time-consuming.

- Anyone who finds a problem, will fix it immediately, resulting in higher quality.

- Knowledge of the system is now shared between team members. Anyone can add functionality or apply changes to any part of the system removing bottlenecks and enabling the fast flow of work through the value stream.

However, with feature branches, each team member works on its own isolated branch hidden from the rest of the team. As a consequence, feature branching works against collective ownership. Code is written by one individual introducing the strong tendency to see the code they wrote as “my code”.

As a consequence, we lose the benefit of being a team. The team now depends on individuals. It is not resilient any more. We now rely on specific team members to change specific parts of the system. Needless to say, this introduces bottlenecks for change, reducing throughput and increasing time to market.

Because feature branching goes against collective ownership, code will tend to be more complex. Adding new functionality becomes burdensome and labour-intensive. Again, this reduces IT delivery throughput and increases time to market.

Because now knowledge of certain parts of the system gets concentrated on specific individuals, it also increases risk.

At last, because feature branching cancels collective ownership, nobody shares the responsibility any more for the quality of the IT systems resulting in reduced stability.

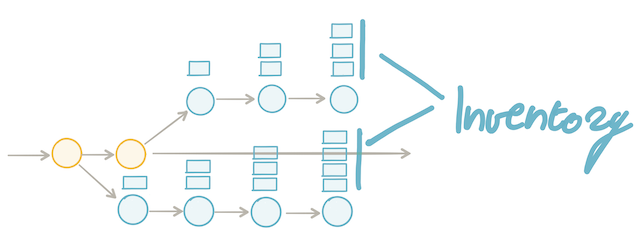

It introduces batch work and inventory

When using branches we introduce batch work. The longer the branch lives and the more changes are accumulated on the branch, the bigger the batch size becomes. Where the batch size is the number of commits that exist on the branch since the creation of the branch.

Taiichi Ohno discovered the drawbacks of batching back in the 1950s at Toyota.

… he made an unexpected discovery – it actually costs less per part to make small batches of stampings than to run off enormous lots.

… Making small batches eliminated the carrying cost of the huge inventories … Even more important, making only a few parts before assembling them […] caused stamping mistakes to show up almost instantly.

The consequences of this latter discovery were enormous. It made [workers] much more concerned about quality and it eliminated the waste of large numbers of defective parts.

… But to make this system work at all […] Ohno needed both extremely skilled and a highly motivated workforce.

– Womack, Jones and Roos, The Machine That Changed The World, p52

Womack, Jones and Roos called this Lean Manufacturing. Later, Mary and Tom Poppendieck proved it also applies to software development. Donald Reinertsen discussed at great length the harm caused by batch work in his book The Principles of Product Development Flow, chapter 5 “Reducing Batch Size”.

The bigger the batch size, the more work we have in progress. The more work in progress the more inventory we have. Inventory is just money stuck into the system.

It is stuck into the system because the organisation invested quite a lot of money to create this inventory consisting of all the code that lies around on all those parallel branches. But this investment does not generate any revenue for the organisation. As long as we have not merged back into mainline, deployed the code into production and released it to the end-users, it does not create any value. Only when this code gets into production in the hands of the users it will generate feedback on how it behaves in production and how it is being used by the users. Only then we can take new decisions and come up with new ideas on how to find new ways to delight the user and solve their problems and needs. This will have an enormous impact on business growth and opportunities.

Remember, the goal of any organisation is to create a positive business impact.

To reduce this inventory, we know from Lean Manufacturing, we have to reduce the work in progress.

This means, working in smaller batches and reducing the lifetime of the branch. Hence, committing more frequently to mainline. This means, integrating more often. As such, achieving a state of Continuous Integration and bringing us closer to a single-piece flow.

Also from Lean Manufacturing, we know that a single-piece flow will increase the IT delivery throughput, increase quality and stability and reduce the lead time for changes, and the time to market for new functionality.

It increases risks

Because long-running branches create batch-work, they also create bigger changesets. Bigger changesets mean more risks.

If we commit more frequently to mainline, the Continuous Integration process will process a smaller changeset. If the build happens to break, finding the root cause will be fairly easy because the changeset is so small. Probably we introduced the failing change just a couple of minutes ago. As a consequence, we still have enough context to easily fix that failing build. In the end, we can fix the build within 10 minutes and hence still achieve a state of Continuous Integration.

On the other hand, when using feature branches, merging back to mainline happens less often. As a result, the Continuous Integration process has to process a bigger changeset. If the build happens to break, finding the root cause will be far more difficult because the changeset is so big. Also, probably we introduced the failing change a couple of hours or, worse, a couple of days ago. This time, we do not have enough context any more to quickly fix that build. Fixing the build becomes time-consuming. From then on, we run the risk of having a broken build for a long period of time. We just lost the monitoring of the health of the application. Accordingly, we also lost the ability to perform on-demand production releases at any given moment in time. Undeniably, this harms lead time and time to market.

When having huge changesets, Lisi Hocke remarks, any kind of feedback activity will find fewer improvements than when you have a small changeset. A small changeset that fits in our head allows us to create a good mental model of it. We can think about the implications and risks. We probably will find lots of small improvements. But, huge changesets on the other hand take already long to just … read through. Not even talking about understanding or even picturing what the impact might be from a risk perspective. Regardless of the effort put in by the author, the bigger the changeset, the more people just want to get done with this as fast as possible. Consequently, the willingness to make improvements decreases. Anything we find, we will often postpone. Finally, it becomes difficult to give feedback. People have spent so much time creating this changeset they might be more reluctant to hear the bad news or to change direction. Because of the Sunk Cost Fallacy.

As we see, increasing the size of changes increases risk. It is essentially the same as deploying our code less frequently. The amount of change is larger and the risk is greater.

This brings us back to feedback. The longer we defer feedback, the greater the risk something unexpected, unusual and usually very bad will happen. We have zero visibility of what is happening on the other parallel branches. Our work may eventually not merge. We could lose days or weeks of work. Which comes with a remarkable cost.

It might impact testing

In all sincerity, this topic requires more thought. The topic is, to tell the truth, more subtle from a test engineering perspective than I initially thought with my limited testing experience. When discussing this with Lisi Hocke, I realised there seem to be good and bad parts to branching about testing. This requires a more in-depth analysis than can be done in the context of this article. Eventually, this will get some more attention in a later article on the consequences of branching for testing.

The good part of branching is it allows us to test the feature in isolation. In this regard, when the feature is broken, it is easier to understand why it does not work. We can check the behaviour in different conditions and simulate different situations. In contrast, this would be harder to check and understand once integrated. Does it not work because of the feature itself or because of the integration with the rest of the system? To summarise, we first try to see if the feature works as expected before exploring, still in isolation, what unknown risks and surprises might be there. All of this gives valuable feedback and information that will feed into the later testing of the integration. Testing the integrated parts becomes then more tangible and focused.

But we are testing twice!? This comes with a non-negligible cost. However, here comes the counterintuitive part. The more we can test in layers along with the incremental development work and the earlier we learn and understand the mental model, the faster we can provide feedback from testing. Not doing this comes with its fair share of downsides. The biggest one is delayed feedback about the implementation.

But, as long as we have not merged back into mainline, we still have no feedback on the quality of our work. The only definitive point is the testing happening at merge time. Do our changes work with everyone else’s changes? Before that, though we collected valuable information, it is still a guess. We do not know. We can only hope nobody did something horrid that breaks our work.

That is where the bad part of branching comes. When software engineers hold back their branch for way too long. When they finally merge we might discover lots of surprises. Either there is a risk they went for too long a time in the wrong direction and we only find out about this too late. Or we end up with long testing cycles finding lots of issues but yet by far not as many or not as relevant as when the branch would have been kept short with a small changeset. Fatigue is a real thing!

That said, having to retest the integrated solution after having tested the feature in isolation has a risk for Testing Theatre. That is exactly where feature branching impacts testing. The test engineer might think “I have already done this” to then not test as thoroughly on mainline. Thereby, defects can creep in. And here we are, damaging the stability and quality of the product.

It introduces rework and therefore makes releases unpredictable

As long as we have not merged back into mainline we simply do not know how much work is still left to do. Merging a single branch into mainline is often not that difficult. Yet, integrating multiple parallel branches is painful. It requires a significant amount of rework caused by merge conflicts, incompatibilities between features and/or conflicting assumptions from team members that need to be resolved and requires multiple rounds of unplanned retesting and bug fixing.

Integrating features into mainline becomes an expensive, time-consuming and wildly unpredictable activity. In consequence, the whole IT delivery process becomes very unpredictable, increasing the lead time, and the time to market for new functionality.

It is expensive and therefore less efficient

Branch creation is cheap and easy. But keeping the branch up-to-date and integrating the latest changes from mainline as well as from all other parallel branches is far more expensive.

The longer we keep our code changes in isolation and do not integrate them with the code changes from other team members the higher the risk the changes will conflict leading to the well known Merge Hell.

This is completely unrelated to the quality of merge tools. Current distributed version control systems have indeed very decent merge tools. Most of the time merges are quite simple and automatic, except when they are not. No merge tool can predict if two features being implemented in parallel, each on their isolated branch, will work together. This can only be discovered at merge time. Again, we have delayed feedback.

The minute we need to manually intervene in a merge conflict, there is a cost. How big that cost will be is entirely unknown until merge time. This results in building up Merge Debt, i.e. the increasing cost of working in isolation on a branch without integrating outside changes.

Merge Debt is commonly caused by:

- Rework at merge-time;

- Wasted time due to rework efforts;

- Risk for lost changes during automatic, silent merges or when manually resolving merge conflicts;

- Or having to throw away days or weeks of work and start over again because differences are so big we are unable to integrate the changes.

The longer we wait to integrate changes into mainline, the more likely the merge pain will get worse rather than better. We are better to take the pain of a merge now so we know where we are.

Apart from Merge Debt, feature branching introduces other significant costs:

- Automated tests need to be executed twice: once on the branch and one more time on mainline after the merge.

- Manual exploratory testing happens also twice.

- Branches introduce batch-work, which in turn introduces inventory which, as we have seen, also comes with a cost.

- Branches introduce higher risks due to deferred feedback and bigger changesets. The longer we defer, the greater the risk that something bad will happen.

It creates cognitive overload

Lastly, it creates cognitive overhead for the team members.

- To start a feature development, we have to create a branch and push the branch to the remote repository.

- To reduce merge complexity, we have to rebase mainline onto our branch frequently.

- To communicate changes between features being designed in parallel, we have to cherry-pick changes between branches.

- To switch work between features - which is never a good idea, but it happens - we have to switch between branches.

- When the feature is dev-complete and merged back into mainline, we may not forget to delete the branch. Otherwise, we end up with a repository having a truckload of branches no one dares to delete. Which introduces another kind of technical debt.

Now imagine the insane context and branch switching for a test engineer inside a team that uses feature branches. It is not just the three branches a software engineer switches back and forth between. It is three branches per software engineer. In a team of five engineers, it means a test engineer juggles between 15 branches. Each branch is a different topic. Each branch has different dependencies requiring reinstalling dependencies with each branch switch. Not even mentioning incompatible database migrations between branches requiring to rebuild the database from scratch. If you were wondering why your test engineer is exhausted at the end of the day, here is your story.

To summarise, to implement a feature, team members have to perform lots of version control operations on a day-to-day basis. Thus, they need to remember a large set of version control commands. This creates cognitive overhead in addition to all the context switching that could slow down the team. Again, this will unavoidably hurt IT delivery throughput, lead time and time to market.

Compare this complexity with the simplicity of having everyone on the team commit frequently to mainline, reducing redundant effort and simplifying the workflow. We pull the latest changes from the remote repository, add our local changes, to then commit and push. This is fairly easy, fairly simple. In the end team members only have to remember a small set of version control commands to perform their day-to-day work.

Conclusion

Continuous Integration is really about exposing changes as quickly as possible to increase feedback.

Any form of branch is about isolating changes. By design, it hides changes for the rest of the team. Although, branches with a very short lifetime (less than a day) can achieve Continuous Integration.

Teams that did well had fewer than three active branches at any time, their branches had very short lifetimes (less than a day) before being merged into trunk and never had “code freeze” or stabilization periods. It is worth re-emphasising that these results are independent of team size, organisation size or industry.

– Dr. Nicole Forsgren et al., Accelerate, p55

But … if less than a day, why bother with the overhead of branches?

[A branch] is antithetical to CI, the clue is in the name “CONTINUOUS INTEGRATION”!

– Dave Farley, Continuous Integration and Feature Branching

Continuous Integration was exactly introduced to obtain faster feedback, to have better, greater insights into the effects of changes. Faster feedback requires more frequent commits into mainline. Forcing us to work in smaller increments, resulting in better, more maintainable code. More frequent commits mean smaller changesets and fewer risks. In the end, achieving a single-piece flow which in turn increases quality and IT delivery throughput together with reducing lead time for change and time to market. Inevitable, this also comes with vastly reduced costs.

Continuous Integration together with Version Control Systems, enable the fast communication of changes inside the team. Surely, this instigates a shared understanding of the system and collective ownership over the codebase. As a consequence, this fosters communication and collaboration inside the team which in turn enables, once more, the fast flow of work through the value stream. Thus, emphasising even more the increase of quality and IT delivery throughput.

To conclude: Do not use branches!

Over the past decade, branching became a standard for most teams. But it does not bring any benefits to the bottom line: deliver quality software in production at speed. To tell the truth, branches essentially slow us down and impact quality! When they can be avoided, a team’s productivity and confidence will drastically increase.

Acknowledgments

As always, thank you to Lisi Hocke and Steve Smith for taking the time and energy to review this quite long article. This would not have been possible without there support.

Glenfarclas, Jura, Bowmore and Black Bottle for keeping me company late at night.

Bibliography

- Continuous Integration (original version), Martin Fowler

- Continuous Integration, Jez Humble

- ContinuousIntegrationCertification

- On DVCS, Continuous Integration and Feature Branching, Jez Humble

- Continuous Integration on a dollar a day, James Shore

- Don’t Feature Branch, Dave Farley

- Continuous Integration and Feature Branching, Dave Farley

- Continuous Isolation, Paul Hammant

- Fake News Via Continuous Isolation, Paul Hammant

- continuousisolation.com, Paul Hammant

- Promiscuous Integration vs. Continuous Integration, Martin Fowler

- Long-Running Branches Considered Harmfull, Jade Rubick

- Accelerate, ch 4 Technical Practices, Dr. Nicole Forsgren, Jez Humbe and Gene Kim

- Git Branching Strategies vs. Trunk-Based Development, LaunchDarkly

- If you still insist on feature branching, you are hurting your business and our profession, Jon Arild Tørresdal

- Extreme Programming Explained, p59, p67, p99-100, Kent Beck

- The Art of Agile Development, p192, James Shore and Shane Warden

- trunkbaseddevelopment.com, Paul Hammant

- Trunk Based Development, Jon Arild Tørresdal

- The Machine That Changed The World, p52, Womack, Jones and Roos

- Branching Strategies, Chris Oldwood

- From GitFlow to Trunk Based Development, Robert Mißbach

- GitHub Workflow vs Mainline Development, Leena S N

- You Are What You Eat, Dave Hounslow

- Why you should not use (long-lived) feature branches, Jean-Paul Delimat

- Why I don’t like feature branches, Paul Gross

The Series

The On the Evilness of Feature Branching series: