In part 4 of this series - The Problems I dived deep into the problems introduced by feature branching. But, what can we do about this? How can we avoid the problems introduced by feature branching altogether?

By adopting Continuous Integration as it was meant when introduced by the Extreme Programming community in the late 1990s. Ensuring always working software on mainline. Allowing us to perform on-demand production releases from mainline at any given moment in time.

This means:

- Everyone in the team commits to mainline at least once a day.

- Every commit triggers an automated build and execution of all the automated tests.

- If the build fails it is back to green within 10 minutes.

Continuous Integration is one of the most critical practices to adopt to enable the fast flow of work through the value stream and to get us close to a single-piece flow. From Lean Manufacturing, we know that a single-piece flow increases the stability and throughput of our IT delivery. It delivers higher quality products. And finally, it reduces the lead time for changes and the time to market for new functionality.

The purpose of Continuous Integration together with a Version Control System is to publish our ideas to the rest of the team and see the impact on others within minutes. The rest of the team sees the direction of our thinking. As a consequence, it accelerates feedback and enables communication and collaboration inside the team. In turn, it helps in gaining a shared understanding of the system and achieving collective ownership over the codebase. Undoubtedly, this again results in better quality, higher IT delivery throughput and unlocks the fast flow of work.

Also, the value of accelerating feedback resides in failing fast. Problems are spotted early, within minutes. We achieve this when committing frequently, multiple times a day, regardless of code complexity or team size. But it requires we work very hard to keep getting fast feedback. This means if the build is too slow, we need to speed up the build; if tests are too slow, we need to write better and more concise tests; if the hardware is too slow, we need to buy faster hardware; if the codebase is too coupled, preventing us to write concise tests, we need to decouple the codebase.

Earlier feedback also results in smaller changesets and better code. Increasing the commit frequency into mainline forces us to work in small incremental steps that preserve existing functionality. We take smaller steps, which generally break less and keep the application always working. We can perform production releases at any given moment in time, as such reducing risks. When we do break something, we can find it sooner and fix it faster, instead of waiting days or weeks to discover it. We also have more context about how to fix broken things than when we commit infrequently into mainline and have to wait for days or weeks for feedback. Here lies an important engineering skill: the ability to break up large changes into a series of small increments. A feature grows over multiple commits on mainline versus designing and implementing the feature in isolation on a branch. Whenever we think the feature is good enough, we release it within minutes. This is possible because we keep our systems always working and always in a releasable state. Consequently, enabling on-demand production releases which in turn again reduces time to market.

We can therefore conclude Continuous Integration satisfies the goal of any organisation to sustainably minimise the lead time to create a positive business impact!

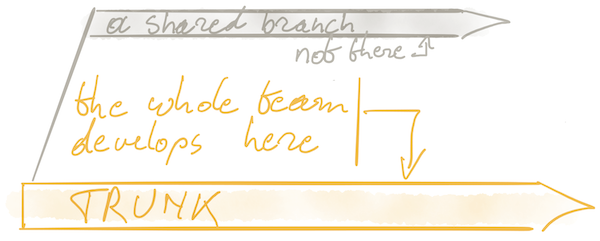

But, Continuous Integration also implies the adoption of trunk-based development.

Trunk-Based Development is what individuals practice to achieve Continuous Integration as a team.

It is a version control strategy in which everyone commits multiple times a day into mainline. As a result, changes are small. Merge conflicts are very unlikely. The codebase is always in a releasable state. Testing happens on mainline. Production releases ideally happen from mainline. If a release needs to be stabilised we can create a short-lived release branch and release from that release branch. In that case, fixes happen on mainline and are cherry-picked into the release branch. It has the advantage we can just delete the release branch after the release without having to merge it back to mainline.

To debunk the classic counter-argument “technically, when cloning a remote repository you are already creating a branch” when I say commit, I honestly mean “commit-and-push”. It is therefore important to regularly pull the latest remote changes, execute a local build and automated test execution, and when it is green push our local changes. All of this is to shorten the timespan of un-integrated code as much as possible.

Nonetheless, there are different ways of practising trunk-based development. Paul Hammant identified three different styles of trunk-based development:

- Commit straight to mainline. This is the traditional way of practising trunk-based development. Also my favourite style and popular amongst Extreme Programmers. It is the high throughput way of working. Still, the biggest challenge here is how long the local build takes to execute.

- Short-lived branches that are merged back to mainline within a couple of hours. According to the book Accelerate it is compatible with Continuous Integration. Also according to Accelerate, it can be seen as trunk-based development when branches live shorter than a day. Yet, I have never seen this work in my humble career. The challenge here is the risk of batching up more commits than if we could push directly; the risk of taking more time and the risk of the slow-review and the slow-build reality that might push us into a multi-day branch.

- Coupled “Patch-Review” system. This is Google’s way of working. All engineers work from head, i.e. a single copy of the most recent version of the code base. When engineers commit, their changes are immediately visible and useable by other engineers. However, changes are reviewed before being committed. That said, Google engineers have their workspace in the cloud and can enable auto-commit. When the review is marked complete and tests pass successfully, changes are committed without further human intervention.

To be frank, trunk-based development is not a recent new hype as I sometimes read on Twitter. To tell the truth, it exists since 1982 when RCS was introduced to replace the first version control system SCCS written in 1972. It supported branches, but teams were very cautious and stuck to mainline.

But, how do we achieve Continuous Integration? How do we prevent it becomes a mess when everyone in the team commits multiple times a day to mainline? Something many teams are most afraid of.

Recently, I identified 14 Practices That Make Continuous Integration. Each of these practices will help us avoid it becoming a mess. Each of these practices is on its own an enabler for achieving a state of Continuous Integration.

Bibliography

- Accelerate, ch 4 Technical Practices, Dr Nicole Forsgren, Jez Humble and Gene Kim

- Continuous Delivery, p. 382 Chapter 14: Advanced Version Control, Dave Farley and Jez Humble

- trunkbaseddevelopment.com - Continuous Integration, Paul Hammant

- trunkbaseddevelopment.com - Styles and Trade-offs, Paul Hammant

- Why Google Stores Billions of Lines of Code in a Single Repository, the paper, Rachel Potvin, Josh Levenberg

- Why Google Stores Billions of Lines of Code in a Single Repository, the keynote at @Scale 2015, Rachel Potvin

The Series

The On the Evilness of Feature Branching series:

- A Tale of Two Teams

- Why Do Teams Use Feature Branches?

- But Compliance!?

- The Problems

- How To Avoid The Problems?

- What about Code Reviews?

- Where is the Evilness?