The usual way to achieve fast Continuous Code Reviews is through Pair Programming or Ensemble Programming. In this article, I will share a less common approach to Continuous Code Reviews using Non-Blocking Reviews.

Update Apr 7th, 2025: add missing links for Gerrit and ReviewBoard.

Somewhere around 2012, I had the opportunity to tech coach a somewhat novice team inside a somehow conservative renowned financial player. The purpose of the coaching was to upscale the team’s software engineering skills. I have already mentioned this team before in On the Evilness of Feature Branching - A Tale of Two Teams. Yes, the one where we practised trunk-based development with a novice team not knowing what we did was called trunk-based development.

A question I often get asked when talking about trunk-based development is: But how do you do code reviews without branches? Implying one needs branches to code review because of the ubiquitous Pull Request.

With PRs we created a world where the amount of time we spend reviewing code has become disproportionate to the time spent creating value.

– Seb Rose (@sebrose), Aug 29, 2022

There are different ways teams can run code reviews.

The one with the minimal impact on flow of delivery is Pair Programming or Ensemble Programming. The code is being reviewed while it is being written before being committed into mainline. Multiple pairs of eyes read the code. We have Continuous Code Review for free.

However, we never got that novice team to pair program. Not everyone feels comfortable with pairing. I respect that. This is something that should not be imposed. Also, because there are unconscious power dynamics in place that are all too often forgotten in the agile community.

We did some pair programming as a learning opportunity. My fellow coach and I sat next to a team member showing how a practice worked or how to achieve something more efficiently. But nothing more. There was, unfortunately, no continuous writing of production code in pair.

Back then, I was a fervent believer in code reviews based on the books Code Complete and Facts and Fallacies of Software Engineering. I saw reviews as a way of improving code quality. But mainly as a learning opportunity.

Given the team was novice, we decided that every single commit had to be reviewed. But I did not want to introduce a hierarchy in the team. So, we introduced peer reviewing. Everyone was going to review the code of everyone, i.e. seniors from juniors but also juniors from seniors. I was not expecting the juniors to find much, though you would be surprised. I hoped juniors would somehow learn something from reading the code from more experienced engineers. This also meant that team members would read the code from my colleague coach and myself. Also, code always had to be reviewed by someone different from the person who wrote the code.

As the team practised trunk-based development, reviews were happening on mainline after merging into mainline. But reviews were still happening on a per-feature level. The feature was the unit of work on our Kanban board. Still, the feature was not the unit of integration or software delivery as we practised true Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery. Every commit that went successfully through all stages of the deployment pipeline could eventually go into production.

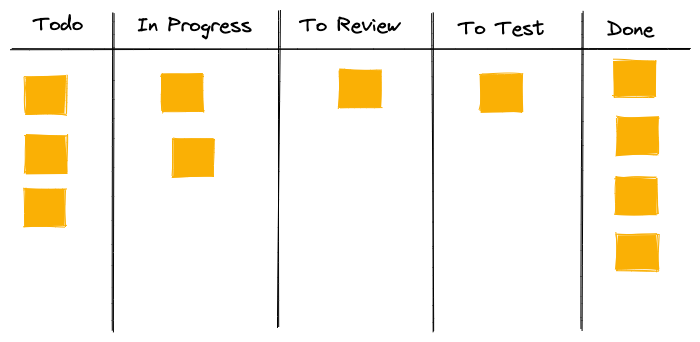

To track the reviews and guarantee we did not forget to review a feature, we added an additional To Review column to the Kanban board.

To avoid context-switching, we also decided that whenever someone finished a piece of work, before starting new work or at the start of the day, they would first check the To Review column to spot whether nothing is waiting to be code reviewed.

We can argue we run the risk of having bad-quality code in production. Yes, you are right. That is possible and that will happen. I do not see a problem over here. First, bad quality does not mean a bug. Code reviews are not there to catch bugs. For this, we have our automated tests and exploratory tests. We had team commitment that any change had to be covered by an automated test, preferably a unit test. We also had manual exploratory testing in place by a peer, different from the engineer that implemented the functionality. Lastly, we had a fair amount of static code analysis that would break the build on rule violations.

For this to work, we need team agreement every commit will be reviewed. Any issue raised during a code review had to be picked up immediately with high priority to ensure this poor quality would be removed from production as soon as possible.

The fact that non-reviewed code can be tested or deployed in production is surprisingly the most significant benefit. We do not ever block the flow of work through the value stream. We can already obtain valuable feedback from testing, and production. We do not have to wait for a reviewer, or worse the ping-pong between reviewer and reviewee, for the feature to be available for testing or deploying into production.

Now the testing part is not totally true as we also had a To Test column. The feature first had to be reviewed before it could be tested. I now realise this was sub-optimal. We could have improved this by making sure the testing did not depend on the review. It would have delivered more gains as made clear in the previous paragraph.

But there is more. Often, it happened a dreadful design came along during a review. That were moments when I wished we practised pair programming to catch these situations earlier. But then again, this was not a real problem. Testing found the feature good enough. In the meantime, it was even already delivered in production. We had all the time to redo the design. Our users already had the benefits of the feature. We could even incorporate the feedback from the user into the new design.

Whereas with blocking reviews, like Pull Requests, a redesign means a delay in delivery. With Non-Blocking Reviews we do not have that. Yet, to be honest, when I have to work with Pull Requests I frequently find myself accepting non-optimal designs to ensure the feature is delivered. But I suggest improving the design. Nevertheless, I always leave that decision to the person requesting the review to create empowerment.

We call this way of code reviewing Non-Blocking Code Reviews. I did not coin this term. In the past, I used to call this reviewing after the fact on mainline. It was only when reading Optimizing the Software development process for continuous integration and flow of work from Martin Mortensen that I came across the term Non-Blocking Code Reviews. I quite liked that term as it better describes the benefit. It does not block the flow of work. It does not block IT delivery. Ever since, I use this term to describe this way of reviewing.

Once, the team was contacted by internal auditors because we did not follow the standard way of working in the organisation. After explaining our process, the auditors had to conclude we did far more quality assessment than the standard process with even better audit tracking.

Alternatives

Samir Talwar shared at the 2022 SoCraTes Germany unconference his experience achieving the same result:

-

Dedicate half an hour at the start of the day where the whole team reviews the commits of the last day.

-

Have an optional half-hour call every day to discuss code with the team.

Tooling

Back then, there was tooling available to support Non-Blocking Reviews:

- With the team, we used Atlassian Crucible. We tagged every commit with the feature ticket number. The tool allows to group all commits based on a ticket number to create a code review. The state of that tool is unclear at the moment.

- JetBrains had a similar tool called UpSource. It has been discontinued.

- There was Phabricator from Facebook. That has also been discontinued. Though, there seem to exist a fork, Phorge.

Although these tools help reach the fast flow of work, vendors are discontinuing these tools in favour of Pull Request-based tooling.

At the 2022 SoCraTes Germany unconference, I met Tomas Skogberg. He works for Auctionet. Tomas shared they practice trunk-based development for ten years. Being confronted with the same situation, Auctionet decided to implement their own code review tool, ex-remit, for Non-Blocking Reviews which is open sourced.

People told me this way of working should be possible with Gerrit, implemented by Guido van Rossum, the creator of Python, for the Android teams at Google. Though, my understanding was that Gerrit blocks commits in the review Git repository before pushing to the main repository.

Recently, I discovered ReviewBoard which seems to work in a similar way as Atlassian Crucible.

No Tooling

But, in all truth, we do not necessarily need any tooling for running code reviews. An engineer can as well guide the team through the code and have a discussion. Though, if we need an audit-trail of reviews, tooling will help.

Definitions

Mainline

The line of development in Version Control which is the reference from which the builds of the system are created that feed into a deployment pipeline.

For CVS and SubVersion, this is trunk. For Git, this is the remote main branch. For Mercurial, this is the remote default branch.

Bibliography

- Optimizing the Software development process for continuous integration and flow of work, Martin Mortensen

- The Talk: Non-Blocking Continuous Code Reviews - a Case Study

Acknowledgment

Dave Farley for nudging me to write this article.

Update Jul 13, 2023: In the mean time, Dave published an excellent YouTube video on the subject: I Found Something Better Than Pull Requests…