In this post, Leena interviews Thierry de Pauw, a Software Engineer who coaches on Continuous Delivery and other Software Engineering Practices. His focus is helping teams to improve the flow of software delivery.

Thierry is a good friend of Leena. He is usually very soft-spoken. But in this interview, he has a lot to say about his exciting career journey. Read on.

This interview taken by my friend Leena was originally published on continuousdelivery.in the 20th of March 2018.

The original article can be found here.

A quick introduction about yourself, i.e. your experience as a Developer, and your journey with eXtreme Programming(XP) & Continuous Delivery(CD)

Unfortunately, I kind of missed the eXtreme Programming(XP) movement. As with many things I have been a late adopter.

My first programming experience started on my parent’s PC XT computer having an Intel 8086 processor. It had a Hercules graphics card. Only two colours, but a very decent resolution of 720x350. I discovered you could do some graphics programming with GWBASIC, a Basic interpreter delivered with MS-DOS.

Later at University, I obtained a Master of Science in Electro-Mechanics (heavy machinery) with a specialisation in production chain management. That was my first encounter with Lean — at the time it was called Just-In-Time (JIT) and Theory of Constraints. Unfortunately, I forgot about it. Recently, while cleaning the attic, I rediscovered the courses at a time I did a lot of investigation around lean.

Although I was somehow destined to study computer science, I didn’t because some dude at the time told me there was a lot of statistics. And I hated statistics. And I have to say; I still have troubles with it.

For a long time, I felt inferior in the software engineering industry because I lacked a formal computer science education, until someone who had a computer science degree told me: “with the knowledge you have, you missed nothing”.

First production application

My thesis was about developing an educative application for solving hyperstatic beams (aka statically indeterminate beams). The application would draw the beam and the forces applied to it according to the specifications given by the user. Based on that, it would then calculate the bending of the beam and resulting forces inside the beam.

Our thesis mentor was a Linux freak and a heavy Emacs user. He heard about the new language Java and suggested we could use if for the educative application. We ended up having a front-end as a Java applet using Java 1.0.x, Apache httpd with CGI and a backend in C. That would have been my first production application.

My professional career started at ClickTouch, an SME of forty people and a leader in membrane switch panels. Together with the production/R&D manager, the two of us were responsible for:

- Managing the machinery park

- Performing research and development around membrane switches

- Managing the IT

- Developing software for both administrative purposes, sales as well as for the machines used in production

- Helping design and build our own machines This was a great time. I was able to balance between the pure engineering stuff related to my education as well as the IT/software stuff.

Career switch — as Software Engineer and Freelancer

Two years later I made the switch to software engineering and joined an IT consulting firm helping organisations with their software problems. Nothing very interesting there, only body shopping. But it got me in touch with the people of Acse, now Acsone.

They were specialised in SGML/XML solutions. They developed a persistent DOM for their document solutions (a NoSQL document store, but for XML) and an XML-RPC framework Xooof for implementing a services architecture before anyone was talking about SOA. I liked that they had chosen a niche, SGML/XML, and they only did fixed price projects. This involved ownership of the team to implement the right thing for the customer.

From agile, they’ve adopted the concept of iterations. An iteration takes a month or two. Not very agile, but at least it was something better than — Big Design Up Front [BDUF]. At the time I started introducing unit testing and continuous integration with CruiseControl on the projects I worked on.

Six years later I made the leap forward and became a freelancer, the best decision of my life. From then on I started taking care of my personal development. I started reading books, going for conferences and code retreats (started with once in a year then twice, later multiple times a year). This was when I started adopting the XP practices.

The next milestone in my career would be Inventive Designers, a Belgian software company of twenty-five people of which ten highly skilled software engineers. I got the opportunity to work on the main product Scriptura, a high volume mail merger. It generates 200 pages per second in different output formats ranging from barcode printers, EPS, PCL to PDF as well as JPEG and GIF.

I always wanted to work for a product company. I always paid a lot of attention to quality, but on projects no-one really cared. So I was frustrated. I hoped a product company would be different. And I was lucky. They did.

This was my first contact with Scrum and a self-organised team. The team was the product owner of the product. They defined which features and/or bugs went into the product, and which ones did not. Sometimes sales and professional services went crazy because a feature didn’t get into the product or was only planned for future releases. I loved this situation. For once, we — the development team — were in control. We could pull work instead of having work pushed on us. Quality mattered a lot to the team. They invested heavily in automated acceptance tests. The product was supported on five platforms (AIX, HP-UX, Solaris, a Linux and AS-400). Every night the tests ran on each platform to detect regressions. Every morning during the stand-up we went over the build failures, and we shared the problems amongst us.

Static code analysis was in place, breaking the build on violations. New rules got added whenever we felt the need. We did code reviews, not systematically, only on bugs and high profile features. The reviews also happened to new feature requirements, making sure everyone understood what was requested.

We had a lot of heated design discussions around whiteboards. But once we came out of the room, everything was ok. This was possible because of the safety within the team.

It was also the first time I got in touch with development at scale. A huge code base (20 million lines of code, 200 projects simultaneously open in Eclipse). Continuous Integration (CI) took 2 hours. By now I know this is not CI ;). Performance mattered.

There were threading problems. It takes a day to reproduce deadlock issues. When you did, you were happy because then the real work starts. Finding a fix usually took only an hour or two.

Looking back, with the knowledge I have now, there was a lot we could have improved. Although, to Belgian standards at the time, this was a high-performing team. The sprints were four weeks long with no option to reduce it to two weeks. It took one week to release the product of which one or two days were for resolving merge conflicts. Builds could have been optimised to get CI within minutes.

Starting with Continuous delivery

And then I got the opportunity to start a technical coaching mission to upscale the software engineering skills of the Operations and Support Tools team at SWIFT — a team of eight persons of which six were software engineers. This is the novice team I refer to in my presentation “Feature Branching is Evil”.

Fortunately, we were two coaches: Martin Van Aken and myself. From him, I learned the mentality — “it doesn’t matter what you do, as long as you do something to learn from it”. It helped me a lot as I used to be a thinker. Not daring to take a decision. Now I gained this just-do-it mentality. Thanks to him.

He brought his startup experience and the drive to deliver as fast as possible to learn and me the high-quality expectations. Over time, this became a great friendship. Now Martin is my go-to person whenever I am in doubt. He likes to make fun of my imposter syndrome and, I like to make fun of me writing better code than he does. Martin is now the CTO of Blue Square.

Add to this a team manager, Stefan De Moerloose, who did put a lot of trust in Martin, myself and the team — a team very willing to learn. All of this allowed us to transform the team from doing 80% operational tasks into delivering value 80% of their time in two-week sprints inside a very waterfall organisation.

The team had higher quality standards than the rest of the organisation. This is where my continuous delivery experience started. That was around 2012. The team was responsible for approximately 20 applications. And we invested a lot in automation, monitoring and being able to release fixes faster.

It was Stefan who pushed me into public speaking. Whenever the team presented their successes, he wanted me to be part of the presentation. But I always declined. I prefer to stay in the background. Then one day he said to me: “You are always repeating us this mantra — if it hurts, do it more often — I think it is time for you to start applying this to yourself”.

What is your definition of Continuous Delivery? Why does Continuous Delivery matter?

IMO, Continuous Delivery is a holistic approach to software delivery with a set of principles and technological and organisational practices. It is not a tooling problem. Most of the time, tooling is the easy part of the problem. I care more about the principles and practices.

Adopting practices are the hard part. It requires room for both learning and practice. It is the adoption of the practices that will get organisations into, what Steve Smith calls, a state of Continuous Delivery. A state of being able to satisfy business demand by delivering frequent product increments with sufficient reliability.

Continuous Delivery is not only an IT problem. It is an organisation problem. The goal of every organisation is to make a positive business impact. And the positive business impact is anything that:

- Generate money (turnover)

- Save money (cost reduction)

- Protect money (being ahead of your competition).

Continuous Delivery will enable organisations to achieve the above goals. It reduces lead time, increases throughput, reduces inventory and reduces operational expenses through automation. Reducing inventory is not so obvious.

Inventory is not so visible in software engineering as it is in manufacturing. But it is still there. Examples of inventory are:

- Version control branches that don’t get merged into mainline

- Unfinished features

- Unused features

- Huge backlogs

Eliyahu Goldratt conveys through his book The Goal that if you improve all three measures (throughput, inventory and operational expenses) together, you achieve the primary goal of your organisation: making a positive business impact. And that is what Continuous Delivery does.

As the team can deploy on demand, how quickly we expose new functionality to customers becomes a business and marketing decision, not a technical decision.

As a result, the business can run more and more experiments because we can perform on-demand deployments and releases. These experiments allow businesses to discover and meet unmet needs of the users and to delight the users. Therefore, organisations achieve an exponential increase in customer satisfaction as described in the Kano Model.

Kano Model

It is the IT — both the development and operations team — that is responsible for fast and frequent deployments. The business is responsible for improving the business outcomes of the releases.

Paul Hammant refers a paper More Engineering, Less Dogma: The Path Toward Continuous Delivery Of Business Value on trunkbaseddevelopment.com. I really would like to read it once to see if they mention things that I may have overlooked. But 499 USD for a report is too expensive for me :(

The reasoning I hear from people about Continuous Delivery is, yes it’s all great. But, where do I start? How do you balance the changes while maintaining the current momentum I’ve for delivering software? Can you provide a few tips to our readers? What is your usual approach with customers?

This is a hard one. As Steve Smith says, there is no set path to achieving Continuous Delivery.

First things first, version control have to be in place. This seems very obvious. And I thought that teams not using version control were a thing of the past. These were situations you encountered in the early 2000’s. To my surprise, I recently discovered that even today in 2018 there are teams that don’t use version control. They update files directly in production. This makes rebuilding production very hard, if not impossible.

So if version control is not in place, I make sure it gets in place as a first action. Without this, you cannot achieve Continuous Delivery. Nicole Forsgren and Jez Humble identified this as one of the key enablers for Continuous Delivery and high performing IT organisations. You can read more about this in their paper “The Role of Continuous Delivery in IT and Organisational Performance”.

Once version control is in place, in the past, I usually focussed on the quality side of the problem. Is there enough confidence about what is delivered? Is it reliable enough? Usually, the lack of confidence results in gating processes such as:

- Endless manual testing

- Code freezes

- Change approval boards.

All these slow down your delivery process. But yet don’t prevent bugs from occurring in production. Jez Humble calls this risk management theatre.

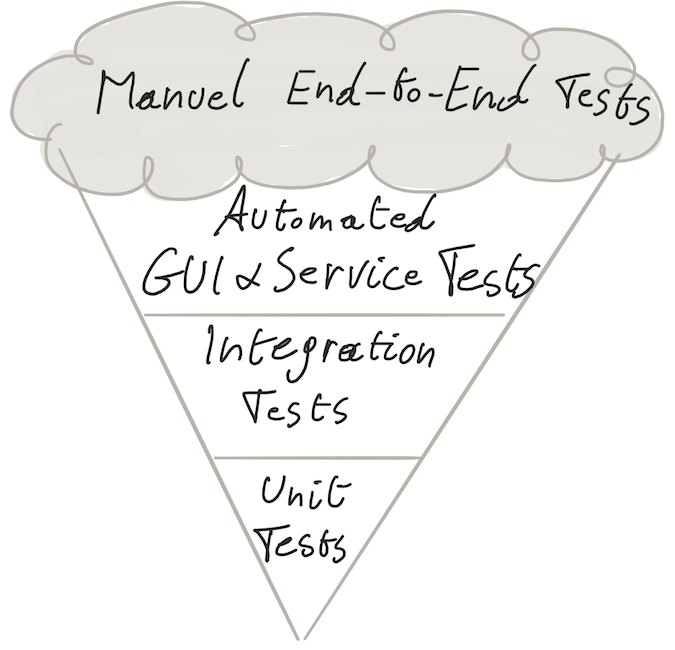

This lack of confidence is usually due to a lack of automated tests resulting in a test strategy that resembles the testing ice cream cone. Lots of manual end-to-end testing, very few or no automated unit testing. I emphasise automated for unit tests because I recently discovered that in some mainframe communities they use the term unit tests for manual tests. So when asked if they have unit testing they cheerfully answered yes ;)

Testing Ice cream Cone — the Anti-pattern

In these situations, I help teams adopt TDD for both unit tests and automated acceptance tests. I do that in a pair programming mode. I sit down with a team member and start working on something from the backlog. This can be implementing a new feature or fixing a bug. I discover the code together with that person.

While discovering the code, I always try to improve the readability (say by renaming variables, extracting chunks of code as a method, removing comments). Once we (or better I) understand the codebase, we add a first failing unit test (or acceptance test), and off you go. After a couple of hours, I rotate and pair with another team member.

I have to say this way of working is always a big surprise. You never know what kind of codebase you will discover. Recently I read Michael Feather’s book Working Effectively with Legacy Code to have more pointers on how to break dependencies.

The simple fact of showing them how TDD works is already a big leap forward. Usually, they just don’t know how to get started with unit testing. Most of the time they didn’t have the luxury to work with people who do this day-to-day. Once they see it, they are easily away with it.

I experimented a couple of times running in-house Coderetreats. Coderetreat helps the team to practice TDD, pair programming and the fundamentals of software design. Introduced by Corey Haines, the purpose of a Coderetreat is to practice the four rules of simple design. TDD and pair programming are a means to it.

Coderetreat takes a whole day where attendees try to solve one problem in pairs over and over again during multiple sessions of 45 min. After 45 minutes, pairs erase their code, we have a 15-minute retrospective and start over again.

This is really about taking time to practice. Compared to sporters or musicians, we — software engineers — do not do enough practice.

Focus on improving the flow

Recently, I started playing with value stream mapping exercises to see if the process has flow. Usually, I limit this from code commit to production deployment.

The purpose is to identify bottlenecks or too many handovers or additional manipulations that break the flow. Bottlenecks can be long manual testing cycles because organisations do end-to-end regression testing, deliveries are waiting for change approvals before being deployed, manual configuration of servers, requesting servers takes for ages, no version control system, ….

Additional manipulations can be not building a package once but building it for every environment which can be a source of risks and additional work as you need additional testing. Using the value stream map, you can easily identify the quick wins and the things that need to be worked on a longer term.

I am yet to try out the Improvement Kata by Mike Rother. Steve Smith mentions it in his book Measuring Continuous Delivery and in his Resilience as Continuous Delivery Enabler article series.

In an Improvement Kata, the organisation defines a goal, a vision of success, around Continuous Delivery. Then it assesses its baseline. What is the current situation?

Once it knows the current situation, it can define the next target that brings the organisation closer to the vision of success. And finally, it can start running experiments (small bets) that get them closer to the next target.

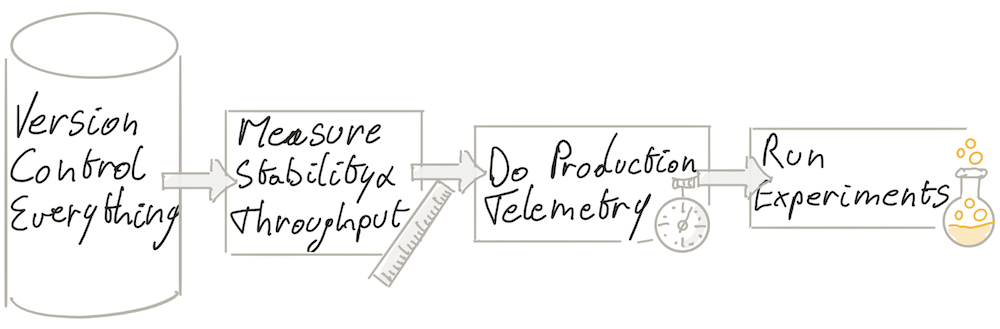

Using Improvement Kata, we follow the below steps to bootstrap Continuous Delivery:

The purpose is to optimise for resilience instead of optimising for robustness. The benefit, as I see, it also fixes the flow of the process. Flow is a precondition to getting throughput and stability.

You start by implementing these actions in short time-boxed iterations.

- Having everything (code, tests, infrastructure, database schema definitions, database schema migrations, network configuration, documentation) under version control will improve stability.

- Introducing production telemetry early ensures that unsafe situations are detected as early as possible which again improves stability.

- Putting in place indicators will ensure the baseline for your future experiments.

Once all the above are in place, you start running experiments on adopting practices that enable Continuous Delivery.

Karel Bernolet confirmed this way of working. At the time we were both coaching teams in the context of an agile transformation at a big Belgian bank. We discussed a lot on how to best coach the teams. His take was, first to make sure flow is back on track. As long as the flow is not fixed, it made no sense investing in anything else. When the flow is broken, you cannot deploy. Once the flow is in place, we can improve the throughput and the feedback cycles.

The point where we disagree on is the urgency of production telemetry. According to Karel production telemetry is important. There we both agree. But as long as you cannot deploy, it made no sense to invest in production telemetry. If you discover a problem in production, you cannot fix it because you cannot deploy. To him, production telemetry subordinates flow. Getting flow under control is best done without applying changes to the final product. As long as you are not changing the product, you run fewer risks of breaking anything.

In my opinion, telemetry has to be in place. And yes, telemetry is about working on improving the feedback cycle. But not having it seems like working in the dark. Somehow you have to know the effects of your experiments. Is it going better or worse? Thus you need a baseline to compare. So you need telemetry to capture this baseline.

I had listened to your talk — Feature Branching is Evil. And we had interesting conversations around that. During the talk, you mentioned the importance of thinking in small batches which is key for TDD and CD. Can you explain a little more on the same?

Yes indeed, small batches are very important. We learned from lean manufacturing that by reducing the batch size, we reduce the amount of work in progress (WIP). WIP is the number of parts being processed in a workstation before they get moved to the next workstation.

If you reduce the batch size by half, you reduce the time it takes to process the batch by half. This means you reduce the lead time by half — the total time parts spend in the plant. And thus, reduce the overall time from the moment raw material arrives at the plant, to the minute it goes out of the plant as a finished product.

Because you are reducing the work in progress, you need less inventory and raw material. This means that less cash is tied up in the system.

In software engineering also, we have batches. Unfortunately, they are less visible. And thus it makes it harder to deal with them. When using branches, we are introducing batch work. The longer the branch lives, the more changes are accumulated on that branch and so the more work in progress we have. Tada, we just created inventory in our codebase.

As long as changes on the branch have not been integrated into the main code base, i.e. mainline, we don’t get any value from it because we get no feedback on how it behaves in production when used by real users. Your batch size, in this case, is defined by the number of commits on the branch until it gets merged into mainline.

To reduce inventory, we have to reduce work in progress. This means reducing the amount of work created inside a branch. So we have to work in smaller batches and commit more frequently into mainline. This results in integrating more often and finally achieving a state of continuous integration, bringing us closer to a single piece flow which in the end will reduce the lead time.

But how do you get there without creating a mess on mainline? Well by adopting incremental software development skills, i.e. working in baby steps and only committing on “green”.

This is where TDD comes into the picture. You start by writing a failing test, add just enough code to get the test to green, and you commit. Then you start your refactoring. If the test is red, revert. If it is green, commit again. And so little by little new functionality is being added into mainline while still keeping mainline working and still being able to perform production releases at any given moment in time.

TDD ensures working software in small batch sizes. Therefore TDD is an enabler of continuous integration and by extension to continuous delivery.

Thank you, Thierry, for taking your time and sharing your experiences. In the upcoming posts, let us talk in detail about a few case studies.