Now and then, I rant about Pull Requests on social media. The rants are on the inefficiencies and the fairly low value of Pull Requests compared to their cost. The friends who understand lean principles appreciate my rants with applause and cheering. On the other hand, there is a fair share of somehow offended people who feel the need to belittle and call unprofessionalism. I guess it is time to provide some deeper argumentation than social media allows.

Update Feb 22, 2024: Add references to research to support the claim “Going slow for safety is a mistake”.

Update Feb 22, 2024: Add the administrative overhead of Pull Requests.

Update Feb 23, 2024: Add “So you would rather let a customer find a bug”.

Update Feb 23, 2024: Add “But, the problem is not Pull Requests, it is the organisation”.

Fucking PRs! 🙄

When the PR is finally approved and merged, damn a bug.

New PR for a fucking one-line change. Really?!? Again waiting for approval.

Several days of delay that could be solved in a couple of hours with trunk-based development and pairing.

Do teams practising pull requests actually want to deliver? I don’t think so. What I observe speaks against it.

Yes, but quality! Yeah right, quality. If that would be the primary reason you wouldn’t use PRs. If one thing is sure, PRs do not improve quality at all. It’s quality theatre.

We would achieve better quality by letting something go into production without any approval that eventually fails in production but that we can fix in minutes, which we can absolutely not achieve with PRs.

Alright, I needed to ventilate. Thank you!

– Me, Feb 19th, 2024

The Good

Decades ago, open-source software gave us the ability for anyone in the world to contribute to a codebase of a public project. Contributors could be on different ends of the world, in vastly different time zones, not even knowing each other’s names for that matter.

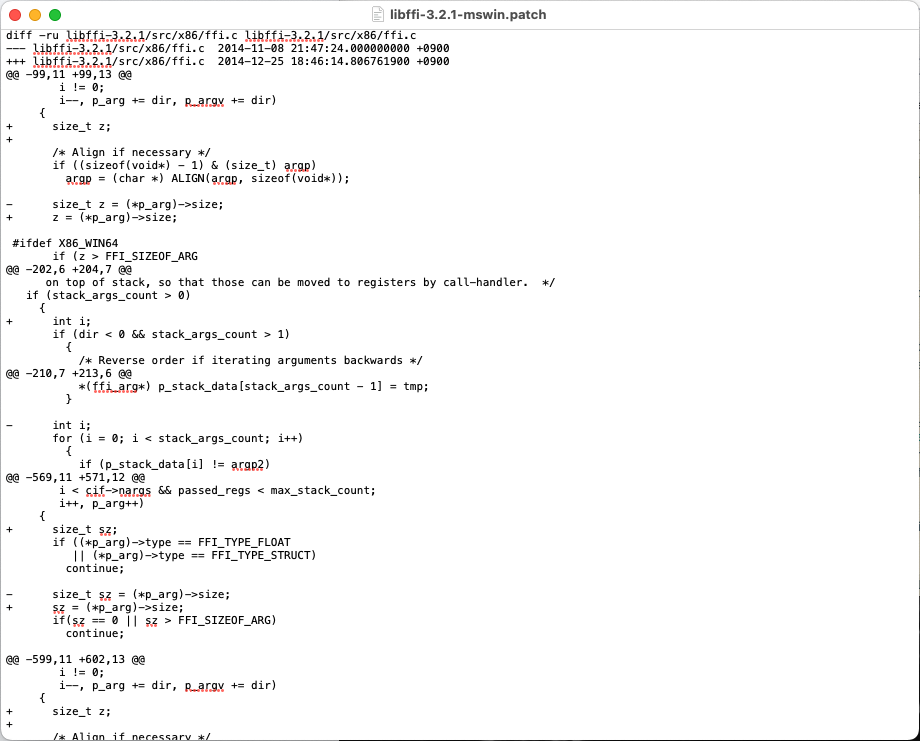

Back then this happened by emailing patch files, which are essentially diffs, to a mailing list. The owner of the project applied the patch to their source code, reviewed it and decided whether to integrate the proposed change or not. A pretty cumbersome process.

Then in 2008, GitHub popularised the Pull Request which Linus Torvalds invented in 2005 shortly after releasing Git with git-request-pull. Essentially, it is a request to pull changes from a forked repository into an upstream repository.

Pull Requests are designed to make it easier to accept contributions from the outside world, from untrusted people we do not know about.

For the Open Source Software (OSS) world, the Pull Request makes absolute sense. That was a game-changer. It suddenly made it easy for people outside the core team to commit. Despite that, the core team can vet that change, suggest improvements and eventually integrate the change. That is the good part about Pull Requests. It improved collaboration and co-creation for Open Source Software.

The Dysfunctional

At the core Pull Requests allow someone to contribute to a codebase they do not have ownership of. That is what the Open Source model is about.

Fast forward, the Pull Request has been transformed into a dogma by all sorts of software organisations without understanding the consequences. The IT industry has transposed an Open Source model into the closed-source corporate world where teams are supposed to collaborate to achieve more and better innovation.

With PRs we created a world where the amount of time we spend reviewing code has become disproportionate to the time spent creating value.

-– Seb Rose (@sebrose@mastodon.scot), Aug 29, 2022

Here is the first problem of applying the Pull Request model to closed-source corporate teams. We are essentially asking engineers to contribute to a code base while denying full ownership of the said code base as they cannot decide whether to accept the change or not. Why the hell would we ask someone to request to put some code changes into something they should already own? That does not make sense at all.

This lays the basis for lots of team dysfunctions.

First, it can introduce an exercise of power. This happens easily when done via tooling, asynchronously instead of face-to-face, synchronously like with pairing or teaming. Who decides which change is accepted and which is not? The team lead? The architect? The seniors? Or do we have real peer reviews where juniors can review seniors, team leads and architects? That is a refreshing idea! I have experienced quite some interesting code reviews coming from juniors. They ask different questions: the outsider questions, the why. Which are good triggers for the necessary improvements.

Second, if reviews are done by seniors, are they trained to have the appropriate mentoring skills? Do they have the ability to communicate clearly and constructively? It is not because they are senior they are good at communicating. Especially, when reviews happen through a tool. That requires a lot of consciousness about the effect of our words and phrases. I have experienced an architect who was pretty bad at written communication. Back then, I was a fairly senior. We could expect I was fairly well protected by my status. Yet, this was a miserable experience. Everyone was telling me, but you know they are a nice person. That can be, but my experience says differently. I never met the person and I profoundly disliked them. It might be, the organisation lost some engineers because of that behaviour.

Third, because this might be an exercise of power, there might be a risk reviews vary in content based on who wrote the code. Whose change is accepted and whose change is not? There is a bias problem that may disproportionately harm.

This brings us to the fourth point, it should not be blaming or harming.

If there is no mechanism in place to curate and train effective code reviews, it is unlikely that the process will be free from any abuse and/or bias. As a reviewer, we should listen, and reflect on the code without judgement, without harming. We provide a willing ear so that others can do a better job at solving a problem. Anyone who can not do that should not do any code reviews.

That too, I have seen and experienced as a senior. One day, a team lead comes to me: “You have approved this and it broke something in production. You should have asked them to add so and so to prevent the problem.”. If a team lead wants team members to take responsibility, to unblock features, they do not act like that. That will have the opposite effect. Team members will not take any initiative anymore. If they do, there is blame when failures happen. Guess what? Failures happen, all the time. That is a fact of life. That is human. That is also how complex systems function. The better answer would be, how can we design the system to avoid this or how can we make sure this is not a big deal so we can easily cope with that?

Fifth, code reviews should not be gatekeeping, which Pull Requests definitively are. The change is accepted or not. As long as it is not accepted, it simply does not arrive in production in the hands of the user. This means functionality, or worse bug fixes are not delivered as long as the review is not finished, and the Pull Request is not accepted and merged. As a result, there is no value delivery. Remember, the goal of any organisation is to make money. At this point, as long as we do not deliver, no money is generated. On the contrary, we incur a cost of delay and an opportunity cost. That is, we lose money.

Would somebody explain to me how a PR that triggers a code review isn’t just a waterfall-phased gate? I see a lot of ppl defending the practice, but I see very little agility in it. Personally, I don’t see reverting to waterfall as necessary or desirable when alternatives exist.

Going slow for safety is a mistake. Research is clear about that. Gates drive down quality. The exact thing we put in place that supposedly should improve quality results in the exact opposite. Think about that!

We found that formal change management processes … have a negative impact on software delivery performance.

…

The motivation behind […] change management processes […] is reducing risk of releases. […] We examined whether introducing more approvals results in a slower process and the release of larger batches less frequently, with an accompanying higher impact on the production system that is likely to be associated with higher levels of risks and thus higher change fail rates. Our hypothesis was supported by the data.

– The State of DevOps Report 2019, p49-51

Longer durations between code completion and review have been shown to negatively impact the effectiveness of the developer and the quality of software delivered.

…

Improving code review speed can contribute to improving several technical capabilities, including code maintainability, learning culture (knowledge transfer), and building a generative culture.

– The State of DevOps Report 2023, p22

But there is more. Pull Requests come with a non-negligible transaction cost.

Transaction Cost

The cost of sending a batch to the next stage.

This is important because the higher the transaction cost, the more inventory we will create in front of the next stage to compensate that cost.

Let us say we want to buy some goods online. To deliver the goods, that cost us 3 EUR. That is the transaction cost. In that case, it is not opportune to buy only one good of 1 EUR. This will not compensate for the transaction cost. Therefore, we will batch up goods to obtain a buying price that is a multiple of the transaction cost so that the transaction cost is offset enough.

Keep in mind, when talking about transaction costs, delays are also one type of transaction cost. This is what precisely happens with Pull Requests.

If it only takes us 10 minutes to make a change, but the change is blocked until a positive review and it takes an hour to receive a review … that means that the change is waiting for 86% of its total lead time. That is pretty inefficient and darn costly. Now, I guess for most teams, one hour is already reasonably fast. I am afraid two hours, four hours or even a day are more common. That means the change waits for respectively 92%, 96%, and 99% of its total lead team. Huh!!!

What will happen now? Two things can happen.

Because of the high cost, team members are incentivised to package more changes into a Pull Request before asking for a review. If we have to wait that long, we might as well add more stuff to compensate for the transaction cost. This, inevitably, leads to bigger Pull Requests. Research shows the bigger the Pull Request the more it suffers from the LGTM syndrome, i.e. Looks Good to Me. How is that improving quality? Tell me.

10 lines of code = 10 issues.

500 lines of code = “looks fine.”

Code reviews.

– I Am Devloper (@iamdeveloper), Nov 5, 2013

It is uncomfortable for people to just wait for a Pull Request to be approved. After all, anyone wants to feel productive. Which is why, they will start new work. This incentivises the creation of more work in progress and loads of context-switching. Work in progress is inventory. Inventory is money, money stuck into the system. It is money the organisation has invested but that does not generate any return unless the changes are put into the hands of the users in production. And context-switching is multitasking. Multitasking is a productivity killer. That is not pretty.

Because of Little’s Law, work in progress has a significant negative effect on total lead time. Higher work in progress means more delays, longer times to market and higher costs of delay. As a consequence, we end with delayed delivery and delayed feedback. Learning decelerates. We become more risk averse. Hence, innovation falls flat. Eventually, we go back to conservative solutions.

To get things out sooner, we need to reduce the transaction cost. We need to minimise the cost of code reviews to reduce the work in progress, accelerate feedback and vastly reduce the time to market.

Lastly, code reviews are not a must. They are optional. It is a choice a team makes whether to run code reviews or not. The team is not more mature because it practices code reviews. The team is also not a bunch of rag-tags if they do not practice code reviews. If the team is genuinely mature, we might think they will do the right thing. Instead of thinking they are stupid and we need a process to fix for that. This is about applying Theory Y over Theory X. This is a matter of having trust in the team. Pull Requests are generally an expression of an absence of trust.

Finally, we have even not mentioned the administrative overhead that comes with Pull Requests. If we only create one request every other day, that is fine. If, on the other hand, we create tens of requests per day, that becomes quite a stressful burden. Notice, that there are now also tens of things we have to keep in the back of our heads because they are not yet in production and as such not done. Imagine the cognitive overload compared to being allowed to continuously deliver one change at a time, from start to end, without any disruptions. Give it some thought …

Well, that is a jolly set of dysfunctions, isn’t it? Now, where is the value of Pull Requests? To ask the question is to answer it.

The buts

“Yes, but letting go of unreviewed code into production is dangerous.” Well, not more dangerous than letting go of reviewed code into production. The number of times obvious errors not covered by automated tests have not been spotted during a review is unimaginable. Yet, they still fail in production. The only response teams have to this is: “We have to be better at reviewing code”. No! The answer should be: “We need to be better at fixing production problems quickly”. Anything that gets in the way of that, needs to be removed. Only then we will improve over the whole line. Consequently, quality will naturally improve. If the code passes all automated tests, we might be reasonably confident it will be ok in production. If it is not, that is not a big deal if we have a process that can cope with that. Pull Requests are certainly not the answer to this. They slow the team down to allow them to quickly fix production problems. DORA identified the Mean Time To Recover as one of the four core metrics that define high-performing teams. Teams should focus on reducing that time, not adding additional barriers in the false belief it will prevent production problems. It will not!

“So you would rather let a customer find a bug than be slowed down? That does not seem worth it to me. What difference does a few hours or days make if it protects your customer?” It is a fallacy to expect a code review will catch bugs. Code reviews are not there to catch bugs. Their principal motive is to improve code quality and catch design problems. Nonetheless, detecting design problems at that point is fairly late. Anyway, automated tests and exploratory tests are far better and more efficient tools to intercept possible bugs. If the code passes all tests, we have code that works. We can deliver it to the users to provide us with early feedback from users using the code. But, even when having a comprehensive set of automated tests in place and practising exploratory testing, bugs will nevertheless happen in production. That is for sure. We better accept that and be good at fixing production problems. Again, going slow for safety is a mistake. It slows down feedback, and as such it impacts quality.

“But we should avoid writing bugs.” Anyone coming with that argument believes in fairy tails or has not seen a production system closely or both. IT systems are complex adaptive systems. They fail randomly in the most unforeseen, unpredictable ways. Of course, we should have automated tests in place. That being said, they will only catch the things we know about the system. We are oblivious to all the unknowns. Because of that, it is impossible to have automated tests that will cover those unexpected situations. The only way we can possibly detect those problems before our customers is through exploratory testing in production and monitoring of production.

“But, there is more to quality than functional quality, meaning there is such a thing as code quality.” True! The automated tests will only catch functional quality. Absolutely, code quality is important. It optimises engineering time to introduce code changes and add new functionality. It increases delivery throughput and reduces time to market. Nevertheless, we can check code quality up to a certain level using tooling as part of the build. Still, this will not catch design problems or naming issues. But then again, as already mentioned earlier, if the code passes all automated tests and all checks as part of the build, this is code that works, but that could be better. At some level that is always the case. A code review may only reduce the chances of releasing lower-quality code. That depends on the quality of the review. It does not eliminate bad quality altogether. Having said that, releasing bad code quality is not the end of the world. We can improve it any time, whenever we see it. Fix the small things. No need to block delivery in a Pull Request to fix code quality. When doing so, we miss production feedback that could help us improve the code. Or we might realise, the users are not particularly fond of the feature. They might not use it at all. So, maybe, we should not invest more time in that code.

“But, I do not trust my code.” Oftentimes, this is an expression of a deeper problem. It happens in environments with legacy code where engineers do not understand the code. They do not have any faith in whether their changes broke the system or not. This also happens in dysfunctional teams having a blaming culture. In those cases, engineers want to protect themselves against that. Therefore, they lean on others to get a sense of faith in their code. To obtain a sense of security, but not true security. It gives an illusion of control. In the end, it is all about diluting responsibility. However, I do not think any process can fix that, certainly not a Pull Request process. That being the case, the organisation has a serious cultural problem requiring profound attention. The Pull Request is in that case the least of their worries.

“But, the problem is not Pull Requests, it is the organisation’s bureaucracy. Pull Requests are the least of your concerns.” Anyone telling that does not understand the mechanics that are in place. Pull Requests slow down. Because of that slowdown, it produces all kinds of misbehaviour that contribute to a pathological or bureaucratic organisation. It is as simple as that. The result is multi-tasking, context-switching, fatigue, stress and burnout which impacts organisational performance. Of course, it is easier to say it is the people, not the process. Then we do not have to face the confrontation we are underperforming.

Code Reviews are not Pull Requests

Pull Requests are code reviews. Though, not necessarily. I can see value in the idea of the automated Pull Request that is automatically merged after a successful run of a build. Yet, I have my reservations on the consequences.

On the other hand, code reviews do not equate to Pull Requests. Being against Pull Requests does not mean eliminating code reviews.

There are many ways teams can run code reviews without Pull Requests that are more efficient.

Pair and team programming are the most effective way to run code reviews while keeping the flow of delivery. We have continuous pre-commit reviews. Multiple eyes are looking at the code while it is being written. Additionally, multiple people are thinking about design. It prevents us from detecting a design that is off at the time of a review when it is too late.

Non-blocking continuous code reviews is another option to run code reviews while not blocking the flow of delivery. Still, it does not protect us from observing bad design at a late stage. But then again, we have all the time to fix the bad design as the feature is already delivering value in production.

Conclusion

For anyone still thinking Pull Requests will save them, I want to finish with this observation …

Information security, auditors, and regulators often put too much reliance on code reviews to detect fraud. Instead, they should be relying on production monitoring controls in addition to using automated testing, code reviews, and approvals, to effectively mitigate the risks associated with errors and fraud.

[…] we had a developer who planted a backdoor in the code that we deploy to our ATM cash machines. They were able to put the ATMs in maintenance mode at certain times, allowing them to take cash out of the machines. We were able to detect the fraud quite quickly, and it wasn’t through code reviews. These types of backdoors are difficult, or even impossible, to detect when the perpetrators have sufficient means, motive, and opportunity.

– someone leading the DevOps initiative at a large US financial services organisation, The DevOps Handbook, Chapter 23. Protecting the Deployment Pipeline, p344

The fraud was quickly detected by employing detective controls using proactive production monitoring, not code reviews.

Pull Requests have the utmost value in the Open Source world. There is no questioning about that.

Outside that world, inside the closed-source corporate world where teams are supposed to collaborate and have high trust to achieve deep innovation, there is no single reason that can justify the cost of Pull Requests in comparison to the somewhat limited to downright absence of value other than defusing the responsibility of engineers and their engineering managers. Or ticking compliance boxes because engineering did not do its homework in having the necessary collaborative conversation with auditors.

But, what is the alternative? Clearly, with pair or team programming we will achieve better quality and higher delivery performance. But, for many organisations, that can be a cultural stretch. That being the case, non-blocking, continuous code reviews are a significantly better approach. However, in all honesty, difficult to implement in regulated industries. Consequently, pair and team programming are superior.

Inspection does not improve the quality, nor guarantee quality. Inspection is too late. The quality, good or bad, is already in the product. As Harold F. Dodge said, “You can not inspect quality into a product.”

– Edwards Deming, Out of the Crisis

Acknowledgment

Lanette Creamer who reviewed my talk “Non-Blocking Continuous Code Reviews, a Case Study” during which she provided me with many insights on the various possible dysfunctions of code reviews.

Related Articles

Bibliography

- 1 Dev, 3 Teams, 3 git pull request review experiences

- A pull request is not really a part of GIT version control. Is it just like a cultural artifact?

- The Talk: Non-Blocking Continuous Code Reviews, a Case Study, Thierry de Pauw

- From Async Code Reviews to Co-Creation Patterns, Dragan Stepanović

- The DevOps Handbook, Gene Kim, Jez Humble, Patrick Debois, John Willis

- The State of DevOps Report 2019

- The State of DevOps Report 2023

- FFS Fix the small things. Some are bigger than they appear, Kent Beck at FFS Tech Conference

- Westrum’s Organizational Topology, IT Revolution